Anti-Assad forces can relish a victory, but their stated aspiration to hold the entire city should be taken with a grain of salt.

Note: Click on the maps to access downloadable high-resolution PDFs.

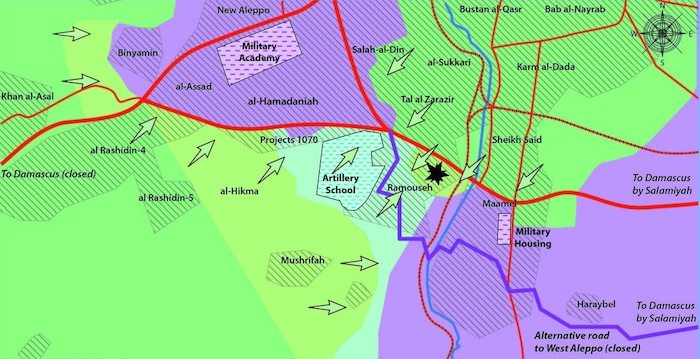

In the past two days, the rebels coming from Idlib have managed to link up with those besieged in eastern Aleppo. An open corridor in the city’s southwest, in the Ramouseh neighborhood, compensates for the rebels’ July 28 loss of the Castello Road, which had connected the rebel districts of eastern Aleppo to the outside (see “Kurdish Forces Bolster Assad in Aleppo”). But Russian aircraft are heavily pounding this new crossing, which limits its use by the rebels. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has reported that although some trucks loaded with produce returned to eastern Aleppo to great fanfare on August 7, the food will scarcely change the lives of the area’s 250,000 residents. Western Aleppo is faring slightly better: the Syrian army opened a new supply route from the north, along a stretch of the Castello Road. Longer and more dangerous than the preceding exit route and capable of being closed off by a rebel offensive in the northwest, the road nonetheless provides reassurance to the 800,000 civilians who reside in western Aleppo.

On August 9, Lebanese Hezbollah’s elite Radwan battalion and two thousand fighters belonging to the Iraqi militia Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba arrived in Aleppo to close the Ramouseh corridor. A fierce Russian bombardment rendered the new supply road to eastern Aleppo unusable — a gesture showing the strong willingness of both Iran and Russia to keep Aleppo on Assad’s side and begging the question: is the rebels’ turnaround sustainable?

REBEL VICTORY SHOULD NOT BE OVERSTATED

Euphoric from the victory, Jaish al-Fatah, a Syrian rebel umbrella group, announced that it would quickly conquer the entire city, but such a goal appears ambitious. Since July 2012, all rebel attempts to hold the western part of the city, where the population does not favor them, have failed. (See PolicyWatch 2499, “Syria’s Kurds Are Contemplating an Aleppo Alliance with Assad and Russia”). However, in 2012-2013, the rebels were mostly nonradical Islamists, which today is not the case. Jaish al-Fatah is headed by a former Jabhat al-Nusra faction — known before the offensive as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham — and includes several jihadist groups, such as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement and Jund al-Aqsa, known for their great brutality (see PolicyWatch 2579, “How to Prevent al-Qaeda from Seizing a Safe Zone in Northwestern Syria”). The recent radicalization of “moderate” groups like Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zinki does not reassure western Aleppo’s urban middle classes. In Aleppo, the major divide between rebels and pro-government factions is not based on sectarian opposition — except for the pro-government Christian minority — but mainly on social class divisions and the historic urban-rural cleavage. Therefore, the chances for an anti-Assad uprising in western Aleppo are nonexistent. If the rebels want to conquer the government-held portion of Aleppo, it will be with a hard fight.

Moreover, the Ramouseh victory took a great toll on the rebel ranks: five hundred killed, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. To achieve this offensive success, Jaish al-Fatah mobilized five to ten thousand fighters and received substantial logistical support from Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, as outlined today in theFinancial Times. In eastern Aleppo, the most concerted military effort to break the siege came from Jaish al-Fatah. On August 1, Jaish broke through the Syrian army’s first line of defense. The fighters were then blocked for a few days at the Artillery School, transformed into a veritable citadel, but several suicide attacks eventually allowed them to break through. Rebels within eastern Aleppo, belonging to the “Fatah Halab operations room,” contributed minimally to the attack, although on August 2 they successfully blew up a tunnel under the Ramouseh district, which allowed them to invade the north of Ramouseh, taking the Syrian army from behind

ALEPPO IS ASSAD’S TOUGHEST BATTLE

In southwestern Aleppo, the rebel offensive was no surprise. Since April, the rebels have worked to retake the villages conquered in fall 2015 by the Syrian army, which had been strongly backed by the Shiite militia Hezbollah, probably Iranian regular troops, and Russian aircraft. But the pro-government offensive failed at Khan Tuman, planting the seeds for the rebel counteroffensive in spring 2016.

Questions thus emerge about why the Syrian army has failed to repel the attack on Ramouseh, with speculation centering on an overconfident leadership, or else a depletion of forces on the southwestern flank caused by the offensive in the north. The Syrian army undoubtedly suffered neglect at the hands of Aleppo commander Gen. Adeeb Muhammad, who was replaced immediately after the defeat by Gen. Ziad Saleh of the Republican Guard — who with Col. Suhail “the Tiger” al-Hassan triumphed in the Castello Road battle. Reinforcements are moving toward Aleppo, and Russia has relentlessly bombed the Ramouseh corridor and the roads between Aleppo and Idlib to slow rebel reinforcements, but whether such efforts will be enough is unclear. In this asymmetric conflict, the rebels successfully countered the regime’s air domination through their greater numbers and method of attack. For instance, in March 2015, they had captured Idlib by staging simultaneous suicide attacks at the city’s entrances, creating panic among the defenders.

The Syrian soldiers, particularly the Alawites, seem less determined to defend Aleppo than Latakia, Homs, or Damascus, because it is not their territory. As for their Shiite allies, if the fight against the jihadists remains a strong motivation, the city of the tenth-century Shiite prince Sayf al-Dawla al-Hamadani has even less symbolic power than Damascus, where the Sayyeda Zainab shrine is located. (See PolicyWatch 2665, “Damascus Control Emboldens Assad Nationally”). All that is known is that the siege of eastern Aleppo will be longer and much more difficult than that of Homs center, where only a thousand rebels occupied just half a square mile. Eastern Aleppo is eight square miles, with ten thousand rebel fighters. Aleppo is located in an Arab Sunni area very hostile to the Assad regime. In Homs, however, the countryside is mostly loyal to the regime, because of the Christian, Alawite, and Shiite presence and Hezbollah’s closing of the Lebanon border to rebels. Despite this, the Homs siege lasted more than eighteen months.

ERDOGAN-PUTIN 2016: ECHOES OF SADAT-ISRAEL 1973?

In geopolitical terms, the 2013-2014 period was less favorable to the rebels, when the center of Homs was under siege by the Syrian army. This morning, Putin and Erdogan met in St. Petersburg in an attempt to normalize relations between the two countries. But if Erdogan really wants to reconcile with Putin, he will need to prove his willingness to stop supporting the rebels. Moreover, Turkey can close its Syrian border, depriving Jaish al-Fatah of logistical support. In exchange, Ankara wants assurances that Russia will not support the construction of a Syrian Kurdistan from the Tigris River to Afrin, along the Turkish border. If the deal happens, however, Erdogan is likely to behave like Anwar Sadat during the Yom Kippur War, when the Egyptian army launched an attack in the Sinai Peninsula to assuage the humiliation of the 1967 war and then to negotiate peace with Israel.

FOR OBAMA, WAITING MAY BE THE BEST OPTION

Finally, what are the consequences of the Jaish al-Fatah victory for the U.S.-Russian agreement against the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda (or “former” branch, although it is difficult to believe no ties remain between Jahbat al-Nusra and al-Qaeda)? U.S. secretary of state John Kerry has promised to unveil details of the agreement shortly. Is the U.S. bombardment of Jahbat al-Nusra on the outskirts of Aleppo part of the plan? This would imply that Washington is helping Russia and the Syrian army resuscitate the Aleppo siege. President Barack Obama may also choose the path of deliberate ambiguity. Waiting to know the fate of arms in Aleppo may be the best option for the U.S. president.

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.