Israel’s Mossad, the second largest spy organization in the West, has grown richer and more sophisticated under Yossi Cohen. But is the director too close to Netanyahu?

On December 14, 2016, Mohammed Alzoari, an engineer living in Sfax, Tunisia, met with a Hungarian journalist of Tunisian origin. For years Alzoari, who, though not a Palestinian himself, was involved in Hamas’ efforts to develop and manufacture drones, had been very cautious about appearing in public and was not well known. But when a journalist asked him for an interview for a film about Palestinian figures – he swallowed the bait.

The interview turned out to be a death trap: From the moment it ended, Alzoari, 49, was apparently kept under surveillance. The next day, while he was driving home, a car drove after him and hit him. Two men emerged from the vehicle and shot him in the head from close range. Immediately after the assassination, Hamasannounced: He is one of ours.

On the evening before Alzoari’s killing, it became publicly known that Israel’s Civil Service Commission was investigating whether Mossad chief Yossi Cohen had accepted gratuities from Australian billionaire James Packer. Cohen was apprehensive that his reputation would be sullied by involvement in the corruption cases in which Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was being investigated, and to which Packer was ostensibly connected. The Alzoari assassination filled him with satisfaction. “Ah, they say it was us?” said Cohen, beaming, in conversations with confidants. “Very good, let them think so.”

In Tunisia, the authorities moved quickly to investigate the incident. In short order they found vehicles and pistols with silencers that had been used by the assassins. The journalist didn’t manage to leave the country and was detained for questioning. The authorities hoped that her arrest would lead to exposure of the network she had worked for, but the more intensely they investigated, the further they got from the Mossad agents who were thought to be behind the killing.

The investigators hoped for a breakthrough when checking the footage of nearby security cameras, but discovered that they had documented nothing – neither the arrival of the car, the assassination, or the getaway.

“That’s not by chance,” a source knowledgeable about methods used by espionage agencies told Haaretz. “A great deal of operational and technological thought goes into dealing with security cameras. The results speak for themselves. Which of the assassinations attributed to the Mossad in recent years were documented by cameras?”

And indeed, in the eight years since the assassination of senior Hamas official Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, in a hotel in Dubai, there have been no reports of a hit attributed to the Mossad that was caught by security cameras.

New methods

Two-and-a-half years have passed since Yossi Cohen was tapped to be Mossad chief. Under him, the agency has undergone a series of changes: It is enjoying increased government budgets, is employing new methods and is engaging in more operations.

The Mossad currently employs about 7,000 people directly, making it the second-largest espionage agency in the West, after the CIA. Anyone passing by its compound at the Glilot interchange, just north of Tel Aviv, will be impressed by the construction going on there, which is barely keeping pace with the rise in the number of employees. Most of that increase is in technology- and cyber-related realms.

Technological developments are obliging espionage agencies to adopt diverse methods of operation: not only to dispatch agents to enemy countries and to recruit local sources for intelligence, but also to dupe people into serving as agents without their knowledge, to use mercenaries and to rely on new capabilities, such as cyberattacks. To avoid biometric identification, as well as to evade security cameras, espionage organizations are being compelled to make increasing use of unwitting local agents. In some cases, complex operations involving a large number of participants are carried out without the agency sending even one operative into enemy territory. North Korean espionage, for example, has apparently used such methods.

Cohen’s predecessor, Tamir Pardo, was extremely cautious. Sources who spoke with Haaretz attested that during his tenure, the Mossad tended to be less adventurous.

“Pardo approved fewer operations,” a former Mossad man says. “The impression in the operations branch was that he was always afraid that people would be exposed. There was a gloomy atmosphere. Pardo may have been right about caution being needed – all the more so because in the end the responsibility was on his shoulders. But the reality was that he barely approved operations.”

When Cohen took over, in early 2016, his goal was to breathe new life into the Mossad’s operational apparatus and to diversify its modes of operation. Although the new methods required more extensive preparation and more personnel, in the end they have borne fruit.

“Some people in the Mossad were skeptical about the ability to carry out such complex operations with the methods he’s been pushing,” says one source involved in intelligence work, “but Cohen imbued them with the confidence that it could be done.”

The assassination of Hamas engineer Fadi al-Batsh four months ago was attributed to the Mossad. The assassins caught up with him in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur on April 21, and killed him with a burst of gunfire at close range. Again, nothing was picked up by security cameras.

This was not the first time that Malaysia was connected with an assassination attributed to the Mossad. A year and a half earlier, the cover story used by the Hungarian journalist who interviewed Alzoari in Tunisia was the making of a film for a Malaysian production company. According to investigators in Tunisia, two Mossad agents who were allegedly operating out of Vienna posted a notice on the internet about needing staff to work on a series about Palestinian scientists and cultural figures in Tunisia. The announcement, which said the series would be broadcast on Malaysian television, drew a response from several Tunisian citizens. They leased cars and rented apartments for production personnel. The Hungarian journalist was tasked with making contact with the target. The assassination itself was carried out by Bosnian citizens. None of them knew the real identity of their employer.

A source involved in intelligence work says that if this was indeed an Israeli operation, it was an amazing one: “The authorities and the media have not claimed that there was even one Israeli on the ground, yet it looks as though the synchronization worked perfectly.”

One of the most publicized assassinations carried out by duped agents of an espionage organization in recent years took place in February 2017. Once again, Malaysia played a leading role. The target was Kim Jong-nam, the wayward half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, who was poisoned upon arrival at the Kuala Lumpur airport when a cloth apparently soaked with a nerve agent was pressed to his nose. Footage from security cameras led the police to two young women, who thought they had been auditioning for a TV show featuring practical jokes. As part of the audition, they were asked to press a cloth to the face of a man at the airport. By the time the police got to the women, however, their handlers had already left the country and the investigation ran into a dead end.

The 2010 Alzoari assassination was probably planned on the basis of lessons gleaned from the killing of Mabhouh. Mabhouh, a Hamas operative who left the Gaza Strip after being involved in the kidnapping and murder of Israel Defense Forces soldiers Avi Sasportas and Ilan Sa’adon in 1989, played a key role in the Islamist organization’s weapons-smuggling apparatus. He was found dead in his hotel room in Dubai; the postmortem showed that he’d been poisoned.

This was actually the second attempt to assassinate Mabhouh, and by the same method. The first time, the toxic substance was left in his room for him to inhale, but Mahbouh felt chest pains and managed to get to the hospital in time for treatment. The second time, the assassins took no chances: They injected him with the poison.

The investigation by the Dubai police traced everyone who was involved in the operation. At a press conference that made headlines around the world, the police exposed a chain of assassins – all of whom had fictional identities and bore false passports.

The Mossad didn’t do anything to dispel the fog surrounding the body responsible for the assassination in Dubai. In internal conversations Cohen simply likes to say that the organization that hit Mabhouh didn’t fail: “If the man was liquidated, and if no one was ever uncovered or arrested [Dubai authorities never claimed to have arrested any suspect], and if all the members of the organization returned home safely – then from the viewpoint of whoever executed the operation, it’s not a failure.”

But while the target had indeed been eliminated, the extensive investigation undertaken by the Dubai police caused diplomatic embarrassment among the countries whose passports had been forged, and exposed operational methods attributed to the Mossad. In addition, the publication of the photographs of the suspects ostensibly uncovered some of the agents who took part in the operation.

A free hand

Much water – and blood – has flowed since Mahbouh’s assassination. The Mossad under Cohen is a large body that uses a variety of means and is active in many countries. For his part, Prime Minister Netanyahu gives Cohen a free hand to do whatever he wishes. The organization’s budget has constantly grown during Cohen’s tenure; it seems that no request goes unfulfilled. In 2019, the budget of the secret services – i.e., the Mossad and the Shin Bet security service – will stand at 10 billion shekels (currently about $2.73 billion) – double what it was a decade ago, on the eve of Netanyahu’s return to power. It will also mark a sharp increase as compared with the 2018 budget of 8.67 billion shekels.

The state doesn’t divulge details about how much money is allocated to the two agencies, but a source familiar with funding procedures says that “the principal increase has been in the Mossad’s budget. At one time the Mossad was a small organization and the Shin Bet was a large body. The Mossad is catching up with the Shin Bet at a dizzying pace.”

Do the increase in budgets and in personnel, along with the apparent multiplicity of operations, necessarily attest to the strength of the Mossad and its success? There’s not always a correlation between the momentum of activity and the realization of goals. Following a series of assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists, which were attributed to the Mossad, international experts thought the liquidations had proved ineffective and should be stopped. The secrecy surrounding such operations makes it difficult to conduct a public debate, whether with regard to the effectiveness of the Mossad and to the steep rise in the public outlay that underwrites its activity.

Cohen, for his part, believes that implementing an effective policy against carefully chosen targets leads to significant achievements. The more those individuals are capable of upgrading the abilities of terrorist organizations, the more Cohen favors chopping them off at the root.

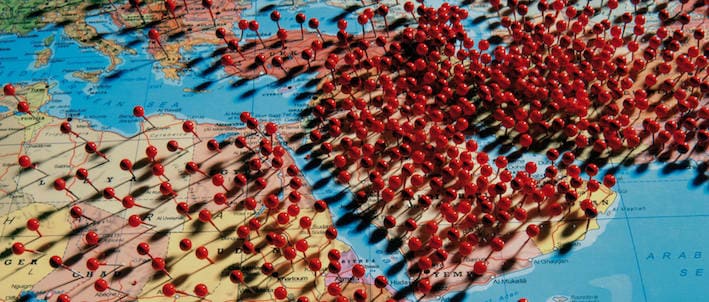

Today, even Cohen’s few critics in the defense establishment point out that the agency’s operative capabilities have been upgraded. “There are many more operations today with greater daring,” says a security source who is knowledgeable about Israel’s clandestine activities. “The Mossad is active in Asia, in Africa. The Mossad’s message to the prime minister is that operations can be carried out in every country in the world, at any time. Yossi imbues people with confidence. He’s less authoritative, more buddy-buddy and a gentleman. He relies on people doing what they’re supposed to do. He’s not out to cover his ass.”

Pal from Down Under

Yossi Cohen was born into a religious family in Jerusalem in 1961. He attended national-religious schools, served in the Paratroops and was recruited to the Mossad at age 22. He is married to the former Aya Shamir. Their second son (they have five children), Yonatan, was born with cerebral palsy. Alongside his work in the Mossad, Cohen devoted much time to caring for his disabled son, who eventually entered the army and completed a university degree. As Mossad chief Cohen has hired dozens of disabled persons for various positions.

Cohen is very sociable, exuding charm, charisma and self-confidence. He’s extremely meticulous about his appearance and about proper nutrition. There are always ironed shirts in his car. He is constantly explaining to his subordinates the importance of being well-groomed. He got his nickname, “the Model,” from Ron Yaron, editor of the mass-circulation Yedioth Ahronoth. In 2005, the paper ran an article about senior figures in the Mossad, and Yaron – who disliked the traditional policy of using initials to conceal the names of such individuals – decided to invent nicknames. Cohen, who cannot be suspected of being overly modest, liked the label and adopted it.

Rising through the ranks in the agency, Cohen became head of Tsomet, the department that runs agents, and Pardo’s deputy chief. However, ongoing friction between them drove Cohen out of the organization. In 2013, Netanyahu threw him a lifebelt by appointing him head of the National Security Council. Two meetings that he had as NSC director would influence Cohen’s subsequent career.

The first was with Sara Netanyahu, the prime minister’s wife. Controversy surrounds the nature of their acquaintance. According to a friend of the Netanyahu family, “Cohen marked the ties with Sara from the first moment as the path that would bring him the directorship of the Mossad. He charmed her the way he knows how to charm people. Before every trip abroad by the prime minister, he sat with her and went over the itinerary carefully. It’s important to Sara to have events that include her, and for there to be free time in the schedule for her and the prime minister to be together. Cohen acceded to every request she made. But make no mistake, he’s a worthy person.”

Cohen dismisses these allegations. In conversations with friends, he has said that he met Sara “ahead of diplomatic meetings. I briefed her on who was coming, his background, a few words about his wife, and that’s it. Since being appointed head of the Mossad, I haven’t spoken with her, apart from polite conversation at events.”

The second meeting was with James Packer. On the eve of the 2015 election back home, Israel’s ambassador to Washington, Ron Dermer, organized Netanyahu’s speech before a joint session of Congress. Cohen was, of course, part of the entourage. As is always the case with the premier before major addresses, he was accompanied by a retinue of rich supporters who have been by his side for the past 30 years. Among those in the VIP gallery were Arnon Milchan, the film producer, and his associate, the Australian billionaire businessman James Packer.

Until then, before Case 1000 (involving allegations that the Netanyahus received lavish gifts from Packer and Milchan) burst into the public domain, Packer was totally unknown in Israel. Cohen met him at the dinner that preceded Netanyahu’s speech. “I simply fell in love with him,” the Mossad chief told members of his close circle. “He’s funny, he’s smart, he loves Israel.” A close friendship developed, which mixed gift-giving with business. At Milchan’s inspiration, and due to the friendship that developed between Packer, the prime minister and his son Yair, the magnate from Down Under started paying frequent visits to Israel.

At the time, Cohen thought he wouldn’t be appointed Mossad chief and started to look for another post. Packer was then planning to establish a large security company in India, and thought Cohen would be the natural choice for director. Along with the thoughts about potential business opportunities, Cohen, who at the time headed the NSC, stayed several times for free in the suite Packer maintains in the Royal Beach Hotel in Tel Aviv. He also received from Packer four expensive VIP tickets for a performance by Packer’s romantic partner at the time, singer Mariah Carey. When the Civil Service Commission started looking into the matter of the gifts, Cohen said that taking the tickets was “a mistake, a folly,” and apologized. He paid the state for the tickets, ending the affair.

AP

Natural connection

The main difference between Cohen and his predecessors at the Mossad lies in the close and intimate relations he has with the prime minister. Netanyahu was suspicious in his dealings with Pardo and the latter’s predecessor, Meir Dagan. Although Netanyahu appointed Pardo, he did so unenthusiastically and with a feeling that he had no choice. There was no great chemistry between them. With Cohen, the connection is synchronized, natural. More than anything, the two share a similar view regarding Iran. Both are convinced that it is a threat that must be fought by every means possible.

After the signing of the world powers’ nuclear agreement with Tehran, three years ago, some Israeli intelligence bodies shifted their emphasis to other arenas, on the assumption that Iranian nuclearization was no longer on the agenda. But Netanyahu continued to oppose the accord, and Cohen decided to make Iran the top priority of his first three-year plan – a decision that helped set in motion the operation to bring the Iranian nuclear archive to Israel.

Cohen backed the unusual move taken by Netanyahu when he went public, with a showcase press conference on April 30, about the seizure of the Iranian archive. His thinking was that since the operation had been exposed anyway, the publicity could contribute to augmenting Israel’s deterrence. But not everyone in the Mossad agreed with him. Some saw publicizing the agency’s work as a cynical exploitation of a professional achievement for political purposes. Some even described their feelings as a genuine crisis of confidence.

Cohen, who embarked on a victory lap of Europe following the revelation of the document heist, totally rejects allegations of the politicization of the accomplishment. He believes, say sources, that the media coverage has helped him augment the intelligence effect.

Overall, he enjoys sharing hints and winks relating to successful operations with journalists, principally from foreign media outlets. About three weeks ago, after the assassination of the Syrian rocket engineer Aziz Asber, which was attributed to Israel, a “senior official from a Middle Eastern intelligence agency” told The New York Times that the Mossad was responsible for the killing. One can only conjecture about the identity of the senior figure who is so well-informed about the operation.

On the subject of Syria, too, Cohen, along with other top personnel in the defense establishment, is pursuing a hawkish stance to which the prime minister is very attentive. Cohen believes that Israel can act freely and aggressively against Iranian targets in Syria, without risk of confrontation with Hezbollah. He believes that in the wake of the nuclear agreement, Tehran has invested significant funding in its operations in Syria, and that it’s necessary to take action against it resolutely and consistently.

Cohen carries out many diplomatic missions for Netanyahu in Europe, the United States, Africa and Arab countries. For example, he handled the contacts between Israel and Rwanda, in an effort last winter to get the latter to accept deported Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers. He has close ties with heads of foreign intelligence organizations and frequently hosts them in the Mossad’s isolated “villa.” His briefings with international counterparts have a uniform political message: Iran, Iran, Iran – like the prime minister’s approach.

With the exception of contacts with Egypt, which are handled by Shin Bet director Nadav Argaman, Cohen has effectively replaced attorney Isaac Molho as the prime minister’s personal envoy. His predecessors in the Mossad became fierce critics of Netanyahu after leaving the defense establishment, but that’s not likely to happen with Cohen. He doesn’t believe in making a distinction between the state and the prime minister.

“I am loyal to Netanyahu,” he likes to say. “He is the State of Israel. The same way that [Ariel] Sharon was the State of Israel and [Ehud] Olmert was the State of Israel. I would serve them all in the same way.”

Cohen’s critics in the security cabinet and the Knesset maintain that his close ties to the prime minister are creating an unhealthy culture, which make it difficult to voice other viewpoints. “He hardly speaks at security cabinet meetings,” one minister says. “No one knows what he is doing, what errands he carries out – he reports only to the prime minister. He doesn’t stimulate [discussion], doesn’t add anything, doesn’t challenge and doesn’t raise objections.”

A member of the Knesset’s Foreign Relations and Defense Committee who has met with Cohen several times adds, “He and Bibi are the same thing. They see Iran as the be-all and end-all. Cohen constantly acts as his spokesman. He doesn’t see himself as the head of an autonomous intelligence body that operates independently, but as part of the prime minister’s policy apparatus. I really hope he’ll be capable of pounding on the table if, in his opinion, we are moving in a dangerous direction.”