*

An accident of the type and magnitude of Chernobyl cannot occur at the Zaporizhzhia plant, both for physical and technological reasons

By Attila Aszódi

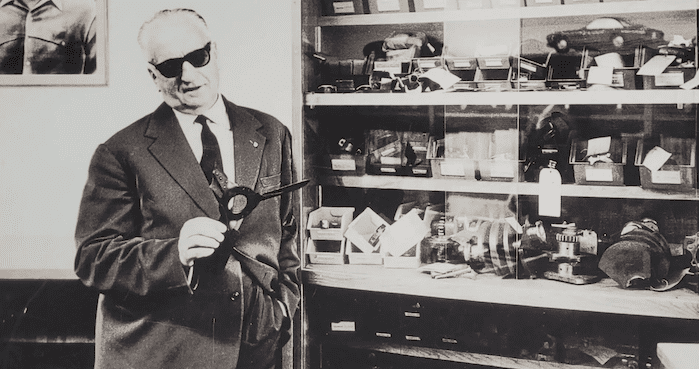

This year’s summer holiday took me and my family to Modena, Italy, where a spectacular new exhibition space commemorates the life and work of Enzo Ferrari, the founder of the revered car brand of the same name. Alongside the beautifully designed cars and engines on display, a little sign got my attention and struck me immediately: The sign explained that Enzo Ferrari preserved the lessons of every engineering mistake he had made for the corporate collective memory. Ferrari would gather faulty parts or sketched notes of accidents in what was known as the “error museum,” a room in which he and his designers would hold many of their meetings. Unfortunately, the “error museum” of the nuclear industry is not a room behind closed doors. It is open for everyone to see. And it is much more spectacular than Ferrari’s.

Nuclear mistakes. Nuclear accidents are embodied in images that are deeply imprinted in the minds of the public, as well as in nuclear engineering textbooks, nuclear safety regulations, and atomic energy acts. The mistakes of the engineers who designed and operated faulty nuclear facilities are remembered much more than those of car designers. The reason for this is obvious: if something goes wrong in a nuclear power plant, the impact on the environment and on people’s lives is much greater. If someone gets injured or killed in a car accident, family members and friends will feel pain, but there is little chance it might affect people living at a distance. But accidents at nuclear power plants are very different. Because the effects of the radiation released from a major nuclear accident can be felt hundreds of kilometers away and can have consequences years or decades later, the accident becomes almost immediately everyone’s business. This makes societies particularly sensitive to events in the nuclear industry.

Unfortunately, the Soviet-Russian nuclear industry has a long list of negative events and a legacy of nuclear accidents. Let there be no misunderstanding: The discovery and development of nuclear power as a new technology came with many failures and accidents in both Western and Eastern countries. But the 1986 Chernobyl accident in the former republic and now the country of Ukraine is one that forever changed the world because of its severe environmental, social, and economic impacts and the secrecy and shocking miscommunication of the Soviet authorities.

It is therefore particularly strange that in recent weeks both Russian and Ukrainian official communications threatened that the artillery attacks at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in southern Ukraine could lead to “another Chernobyl.” The world now watches with astonishment and concern as to how such a scenario could happen, and by what logic one could think of threatening their enemy—and the whole world—with a military attack on a nuclear facility.

Beyond the design basis. Armed attacks—or even threatening an attack—on civilian nuclear facilities are contrary to the principles enshrined in the charter of the United Nations and the statute of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Wherever this happens, it is unacceptable and must be strongly condemned by the international community.

The crisis now unfolding at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant violates the fundamental principles of the nuclear industry which are to ensure the nuclear safety, physical protection, and safeguards of any given nuclear facility. The crisis at the Zaporizhzhia plant also makes it impossible to work professionally in those fields, and so it increases the risk of human error by several orders of magnitude.

Nuclear power plants are designed to withstand a range of external and internal hazards, which are considered in determining their design basis. But not a single nuclear power plant has been designed to store large quantities of ammunition or to be regularly shelled by artillery. Artillery attacks on the nuclear power plant site, or the stockpiling of large quantities of explosives and munitions on the plant site, or the laying of mines by any party, create additional risks for which these facilities are not designed. The Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant is now in a situation that is outside of its operating licences. The risks at the plant must be reduced to their design levels as soon as possible.

No responsible government, authority, or operator should behave in a way that deliberately creates and maintains a significantly higher than normal risk condition that is beyond the design basis of a nuclear facility. The IAEA’s Fundamental Safety Principles clearly state that “[t]he fundamental safety objective is to protect people and the environment from harmful effects of ionizing radiation.”

Five urgent steps to ensure safety. In application of the fundamental safety principles, the following technical steps would help respond logically and appropriately to the present crisis at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant.

First, if both parties involved in the conflict consider that an artillery attack on the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant from either side cannot be ruled out, all reactors should be shut down immediately and brought to a safe cold shutdown state. This measure would reduce by many orders of magnitude the amount of radioactivity present in the reactors potentially released in the event of a core damage accident, and so this protective measure would reduce potential environmental consequences.

Second, Ukrainian authorities should revoke or suspend the operating licenses of all six units at the Zaporizhzhia plant. The large quantities of explosives and artillery equipment reportedly present at the plant’s site are an external hazard for which the units were certainly not designed and licensed.

Third, the Ukrainian operators still working at the plant are not free from external influence due to the presence of the Russian military and Rosatom technical staff at the plant. Therefore, the organizational conditions for the safe operation of the plant are not met. This also supports the view that the units should be shut down. Normally, any modification to the management system of a nuclear installation should be preceded by a safety analysis and regulatory approval. If this has not been done here, the plant is operating outside the conditions laid down in its operating license, which is contrary to international standards and legal requirements and therefore cannot be allowed to continue.

Fourth, an extraordinary stress test of the Zaporizhzhia plant is necessary; such a test would consider the consequences of the new external hazards and the organizational change. The units should only be restarted responsibly once the stress test of the units has been successfully completed and the necessary technical and administrative corrective measures have been taken to ensure that the plant returns to its normal operating conditions.

Fifth, and last, the ongoing expert mission led by the International Atomic Energy Agency is important, as it can greatly increase transparency and help assess the situation at the plant more accurately. But a mission, if successful, is not a substitute for the above steps.

Being familiar with the international regulatory practice in nuclear safety and the design principles of nuclear installations, I know that the above measures would help reduce the risks to acceptable levels. In addition, however, it would be necessary for the involved parties to refrain from any artillery and military activities at and around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. Artillery and explosives should be removed from the facility and the plant restored to a condition consistent with its design basis.

An accident of the type and magnitude of Chernobyl cannot occur at the Zaporizhzhia plant, both for physical and technological reasons. Suggestions about an accident of this magnitude may be aimed at frightening the European public and political decision-makers. Such rhetorical threats are political in nature and not based on technical grounds.

If one is serious about nuclear safety and does not want to add another exhibit to the nuclear industry’s error museum, the above five steps are urgently needed to ensure that the risks associated with the plant are reduced as soon as possible to the normal levels set out in the rules and legislation for the Zaporizhzhia plant.

Editor’s note: Attila Aszódi is a nuclear safety expert and the dean of the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. The article expresses his own expert views, not those of his institution.