“Come out, you donkey!” the Syrian rebel shouts in Arabic in the amateur video that appeared on the Internet in mid-October. Two other rebels are pulling something out of a pile of rubble. The outline of a human body appears from beneath dust and bricks.

The scene resembles something out of a movie—the aftermath of an entire building collapsing on the people inside. Only this is real. Twelve pro-regime fighters reportedly died in the destruction of this structure north of Aleppo in war-ravaged northern Syria.

Three soldiers survived. Islamic Front rebels pulled them from the wreckage and took them prisoner.

Islamic Front fighters are no angels, but their interrogation of the prisoners, which the rebels also recorded and posted online, is a surprisingly civil affair.

One of the captured fighters sits on a sofa, a bandage on his head. The rebel sitting beside him asks where he’s from. He answers in Dari. “Afghanistan,” he says.

This is not the first time Afghans have been caught fighting in Syria, for or against the regime of Syrian president Bashar Al Assad. Some Afghan fighters joined Al Assad’s forces after rebels came close to capturing the shrine of Sayydah Zeynab in southern Damascus.

A number of Afghan Shias have been living around the shrine since the early 1990s, when the Taliban started massacring Shia Afghans, forcing many to flee the country.

In early 2012, a suicide bomber blew himself up at a bus stop near the shrine. Syrian security forces claimed the truck was heading to the holy shrine itself. The apparent near-miss enraged Afghans in Syria and back home.

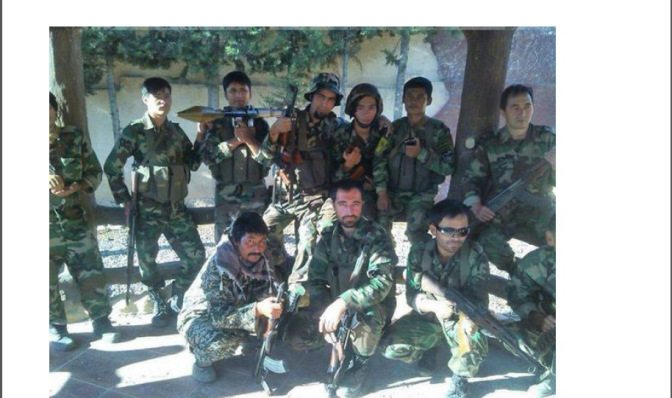

In late 2012, the first Afghan members of the pro-regime Al Abbas Brigade appeared in pictures circulating in jihadist social media. Afghans were going to war in Syria. In early 2013, Afghan volunteers along with Pakistani, Azeri and other Asian fighters reorganized as the Fatemiyoun Brigade.

And soon, the motivations seemed to change for at least some of the Afghans.

Videotaped interrogations of two of the Afghans the rebels captured in Aleppo reveal that, for them at least, the war isn’t about ideology anymore.

The Afghan with bandaged head says he’s from Varamin, an impoverished town near Tehran. He’s an illegal immigrant. Iranian authorities had apprehended him and offered him a monthly payment of $600 to fight in Syria. If he had refused, they would have sent him back to Afghanistan—which for a Shia could mean death.

There are an estimated one million illegal immigrants from Afghanistan living in Iran. They and their children can’t enroll in universities or work regular jobs with standard benefits and pay. Afghan immigrants tend to work in construction or as farmers.

They live in the poorest neighborhoods, suburbs and villages. Afghan communities in Iran are prone to crime, mainly drug trafficking.

It was the fall of 2013 when Afghan fighters in Syria first made headlines in Iran and Afghanistan. A large group of Afghan fighters tried to penetrate rebels lines outside Aleppo in order to help loyalist fighters trapped in the city. The rebels ambushed the infiltrators and killed 17 of them.

Pictures of the victims seemed to depict some very young men, possibly minors, although it was impossible to verify anyone’s actual age.

Considering the low living standards of Afghans in Iran, from the beginning the main assumption was that Iranian authorities had more or less forced these Afghans to fight in Syria, offering them modest pay and threatening extradition if they refused.

Afghan officials launched a formal investigation of Iran’s alleged recruitment efforts. Members of Afghanistan’s parliament including Shokriye Peykan have openly accused Iran of taking advantage of poor Afghan immigrants.

Hamed Eghtedar, an Afghan who has lived in Syria for more than six years, said he believes that while some of Afghans fight for money, there are still others who fight for ideological reasons.

Indeed, some Afghans—members of the Pashtun nationalist Mellat Party, in particular—have gone straight to Syria from Afghanistan to aid the regime, skipping Iran entirely.

Eghtedar, a correspondent for the Bokhdi news agency in Afghanistan, said he has seen Arab and Chechen fighters carrying Afghan passports while fighting for the rebels in Aleppo. They allegedly travel under Afghan aliases to avoid prosecution in their home countries.

Given the large number of Sunni Afghans fighting for the rebels, the Al Assad regime considers Afghans a possible threat. Regime troops even abducted Eghtedar and his wife near Aleppo. Al Assad’s forces tortured Eghtedar for 45 days before releasing the couple. The torturers’ usual technique was to bash his head against a wall.

Eghtedar and his wife fled Syria and and returned to Afghanistan by way of the human-smuggling route. Traffickers charge up to $1,000 to sneak a person out of Syria.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHzKvwXLY7E#action=share

Moradli’s interrogation. Islamic Front video

In the other video of October’s Aleppo captives, the captured Afghan introduces himself as Ali Moradli. He says he’d been sentenced to six years in prison for dealing drugs in Iran. Again, authorities offered $600 per month to fight … or extradition.

The Iranians sent him to a five-day gun-familiarization course then flew him to Damascus on a civil passenger plane.

After two days in Damascus, his unit flew to Aleppo. They traveled one hour by road then hiked for eight hours to reach their front-line base. Combatants from a nearby Shia town guided Ali’s unit across the mountains and deserts north of Aleppo.

According to Moradli, the Afghan fighters numbered 450. They were organized as three 150-man battalions, each consisting of 10 squads of 15 fighters. Iranian officers lead the battalions.

Ali says his Iranian commander would have killed him if he had tried to run. But then the rebels attacked, killing the Iranian commander. The only Iranian known to have died in Syria in same time period is Brig. Gen. Jabbar Darisavi.

Moradli says his squad commander was named Khalili, but Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps members usually use aliases in the field. Tehran announced that Darisavi died in the Handirat region north of Aleppo — the exact location of the ambush.

Darisavi, a battalion commander during the Iran-Iraq war, more recently served in the Karbala Intelligence Joint Headquarters in southern Iran.

Moradli’s inadequate training plus the fact that Iranian generals are leading indentured Afghan drug dealers is indicative of Tehran’s—and the Syrian regime’s—desperation.

When Islamic State invaded Iraq this summer, Iran diverted its Iraqi militias to defend Baghdad. Likewise, Hezbollah has had to pull out of Syria and return to Lebanon in order to defend against Syrian rebels pouring out of the Qalamun Mountains.

The pro-regime forces that remain in Syria are ill-prepared and thinly spread. If the Afghans’ capture in Syria tells us anything, it’s that the regime and its allies are running out of people.