The recent publication of Fouad Ajami’s memoir of his youth in Lebanon comes as the eight anniversary of his death nears on June 22. The memoir is a highly moving account that describes a period of Ajami’s life about which he often spoke little, as he always maintained an ambiguous relationship with his country of origin. Most revealingly, we learn that when he wrote about the Shia Lebanese experience, he was describing what he had lived through himself, intimately and intensely.

For a long time Ajami was a controversial figure in Middle Eastern academia in the United States. His detractors saw someone who had become an intellectual handmaiden of American power, as when he defended and promoted the U.S. invasion of Iraq. To them, Ajami had also shifted position on one of the great Arab causes, abandoning his concern for the Palestinians to side with their enemy Israel. Most objectionably, Ajami distanced himself from his Arab origins, preferring to refer to himself as an American and rejecting a hyphenated identity of the kind that has prevailed in the increasingly polarized culture of the United States.

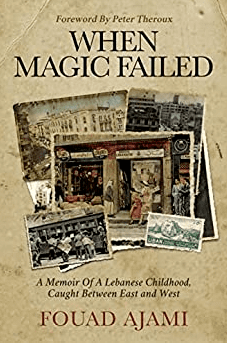

As time passes, however, that sectarian debate retains little interest. Which is why Ajami’s memoir is the right context for drawing attention away from it. When Magic Failed: A Memoir of a Lebanese Childhood, Caught Between East and West, was an unedited manuscript when Ajami passed away. His wife, Michelle, readied it for publication with assistance from her husband’s friend Leon Wieseltier and an editor, Benjamin Kravitz. The result is an impressionistic memoir (the word “magic” in the title seems to refer to the “magical realism” identified mainly with Latin American authors, in which reality is blended in with fantasy).

However, what is particularly striking is the extent to which Ajami experienced firsthand the cycles of Shia integration into the Lebanese state after independence in 1943. Born in Arnoun in 1945, his early years were spent in his village, situated in the shadow of Beaufort Castle. He later moved to the poor quarter of Burj Hammoud, part of Beirut’s eastern suburbs that would become landing points for other Shia making their way to the capital—including Sayyid Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah and the family of a young Hassan Nasrallah. Those were years when Ajami and his brother lived with their mother, who had been abandoned by their father after he met another woman. While the boys went to their father’s school in the neighborhood, theirs was an unstable existence, that of “[stepchildren]without means, without great claims …”

One paradox here is the matter of social mobility. A central theme of the book is that in Lebanon one tends to remain a prisoner of one’s social stratum. But in fact Ajami tells a different story. As a young boy living with his mother, he was quite simply poor, living among the rural migrants and Armenian refugees of Burj Hammoud. His mother sewed clothes to make ends meet, ensured that her boys maintained an acceptable standard of living, and insisted “on her distinction and ours.” Throughout the book, one senses Ajami’s resentment for what his father did to his mother. Many years later, he would tell a class that Arab culture could be cruel to discarded wives and their children, even if his own fate qualifies that.

When Ajami’s father returned several years later from working successfully in Saudi Arabia, Fouad and his brother suddenly found themselves elevated to the urban middle class. They moved into a building their father had built in western Beirut thanks to his earnings, and Fouad was placed in the prestigious International College. While this trajectory was not especially unusual, it did two things: It gave Ajami an American education, which would prepare him for his departure for the United States in the early 1960s, leaving behind a country he found increasingly suffocating; and it allowed him to break with his rural origins, despite his love of Arnoun, so that he came to absorb the ambitions of an urban upstart, a budding Rastignac. This only alienated him more from a society that thwarted all ambition.

However, it would be a mistake to read Ajami’s memoir as a settling of scores with Lebanon. On the contrary, what is so poignant in his book is the extent to which it shows that even decades later he was unable to shake off the old country. In her acknowledgments, his wife recalled that he insisted that the word “Arnoun” be placed on his headstone. Throughout his career, Ajami was strangely attracted and repulsed by Lebanon, a love-hate relationship whose interplay would not wane.

Certainly, his research reflected this preoccupation. The first time I met Ajami, in September 1985, he spent a good 20 minutes discussing the Shia revival in Lebanon, before handing me his latest article from Foreign Affairs, “Lebanon and its Inheritors.” He was then preparing his book The Vanished Imam, Musa al-Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon, and only in reading his memoir can we understand how Ajami later came to see his otherwise anonymous life as one with a broader, inexorable Shia current. That many other Shia felt they were part of something bigger explains why Musa al-Sadr was able to rally the community around a quest for affirmation.

Ajami’s major books are all of a theme, each following on from the other. The Arab Predicament told the story of the collapse of Arab nationalism in the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war. From there, it was a natural step for him to focus on Musa al-Sadr and Shia mobilization, since Shia identity was one of the byproducts of the failure of the Arab state and a larger Arab identity. His masterpiece, The Dream Palace of the Arabs: A Generation’s Odyssey, carries this tale of woe further, showing how a generation of Arabs, the generation of optimists that had emerged from the years of Arab revolutions and liberation, which sought to advance dreams of “secular nationalism and modernity,” ultimately was crushed by Arab regimes that swallowed their children. The Foreigner’s Gift, which praised the United States for removing a tyrannical regime in Iraq, sought out a narrow filament of hope in the region. However, by the end, Ajami could see that this was an all-too-brief interregnum, one that most Americans considered a terrible mistake. His book on Syria, The Syrian Rebellion, illustrates how the United States moved away from advancing any kind of emancipatory project in the Middle East. As Syrians were slaughtered, the Obama administration stood by doing nothing.

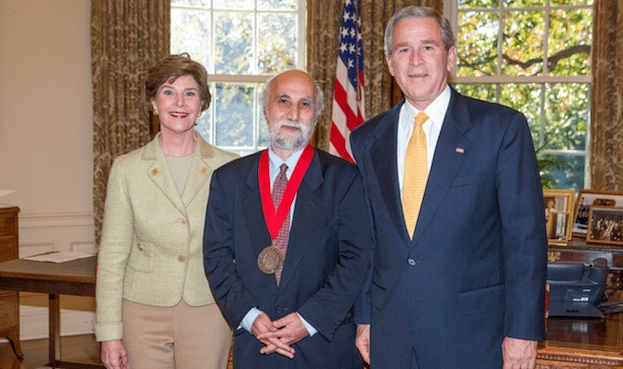

The release of his memoir somehow brings Ajami’s intellectual path full circle, home. When he died, many of his American friends remarked on how fundamentally American he was. It was as if his repeated use of the word “we” in describing America, as if the long period of time spent far away from Lebanon without visiting, entitled him to the compliment of being “one of us.” Such an interpretation suffers from overstatement.

America is ecumenical in its embraces and can be munificent in its generosity. However, Ajami’s book reminds us why a part of him never left home. His longing for emancipation, as he knew too well, was in him an Arab impulse, even a Lebanese one, toward which a vast majority of Americans remained indifferent. Ajami writes that the love he felt for his birthplace was really only “fidelity to childhood—to those fragments of our lives that we yearn for and fear.” But was it only that? I closed his book convinced that Ajami must have remained all too conscious of how unlike Americans he was, and his memoir provides insights into how Lebanese he remained. Nothing else can explain the fear he describes of his country that wouldn’t let go. We dread most that which is ingrained in us.