Some might say that the spirit of the modern age, at least in the developed West, is all about an exaltation of the self, or about the primacy of personal choice, or about sexual fulfillment and other hedonistic pleasures. Some critics might point to a spiritual malaise with ancient roots.[1]

The spirit of acedia affects many people today, but perhaps particularly today’s youth. The term comes from fourth-century desert monastics who likened it to sloth, and which we would categorize as ennui or boredom.[2] The monks, of course, attributed not only a physical aspect to this term, but also a spiritual aspect as well, which for them was more important and more dangerous. The danger inherent in acedia was that it could lead someone further and further astray. In this modern age we may be tempted to say that the simple cure for something like acedia would be for the afflicted individual to work harder or to be more active in their life; however, the reality faced by those suffering from acedia is quite different. It has been likened to depression, and while there are many similarities between the two, there is one very important difference.

Kathleen Norris has written extensively on this topic and distinguishes between the two by the treatment each warrants.[3] Someone who suffers from acedia can be depressed, but while depression calls for a physical diagnosis and treatment, acedia has no physical basis for diagnosis, and seems, therefore, to require a different sort of remedy. In short, depression represents a physical or mental malady treatable by physicians and medication, while acedia exists as a spiritual malady in need of a spiritual means of healing, or at least of some kind of more metaphysical treatment. Some see the malady as modern man’s need to fill his existential fear of death with something, anything, often empty entertainments.[4]

This lack of purpose is one reason why the Islamic State (ISIS) can so easily recruit those suffering from acedia. Of course, there is no one single profile for those in the West inspired to join ISIS: there are poor and comfortably middle class, converts and second generation Muslim immigrants, people with lousy jobs and with good jobs, youth rebelling against their parents and life-long Islamists. But no one can deny that the Salafi-jihadi siren song of ISIS, selectively mined from formative Islam, bestows their recruits with a sense of, often deadly or fatal, purpose, even a seemingly grand and noble mission, to establish a new Islamic caliphate and to build a utopian state ordained by Allah to rule the world. Instead of a drifting, confused identity, ISIS offers a distinct and supposedly superior one. The fact that the reality of the actual ISIS state is rather more sordid is lost in the social media glitter of the moment. A connection can also be made with terrorism’s attraction to a subset of people with mental illness.[5] Certainly delinquents and petty criminals are not uncommon in the ranks of the Islamic State. Indeed, its most seminal precursor, Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, perfectly filled that bill.[6]

To strengthen the precarious frame of mind in those suffering from acedia would be to instill a sense of purpose in these individuals. But if purpose can be understood to represent strongly held beliefs that constitute a firmly defined worldview, then it is no wonder that youths in the West, a small minority of them but still an unprecedented number, are at risk for ISIS recruiters.[7] Fighting the spirit of acedia is something that can only be really accomplished on an individual, personal, and private level. It is more the work of religious leaders, teachers, leaders, parents, mentors, and psychologists than law enforcement officials or national security. And, obviously, governments and nation states have a rather bad record in instilling deadly purpose into their populations.

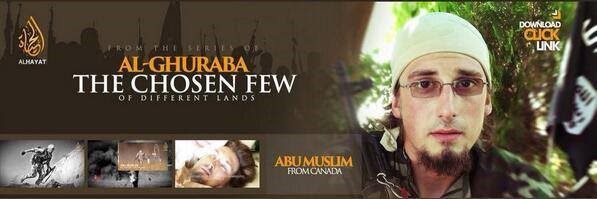

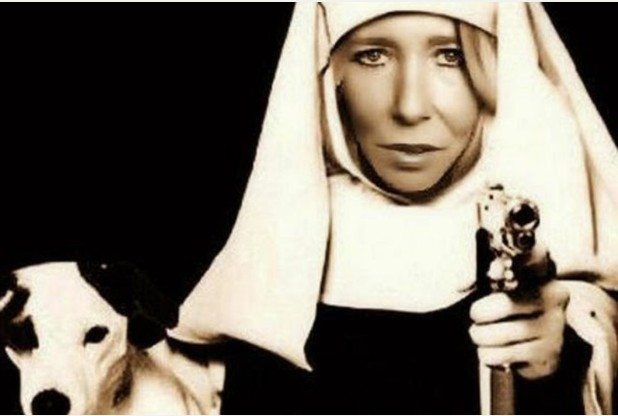

In this modern age, youths have a difficult time establishing and finding a sense of purpose. Life in the West can be both comfortable and stultifyingly banal for some. For many, the idea of going to college and being ensured a job is a holdover from an older generation and it simply does not quite hold true in this day and age. While the job market has supposedly stabilized, it has also become increasingly competitive, and if people are to find purpose in life, it may be something outside of the typical avenue of work. Anyone working at a dead-end job can attest to the difficulty of finding purpose and satisfaction in their work, especially if they have tried to find better prospects and have been met with failure again and again. Canadian convert Andre Poulin, star of one ISIS video, had progressed from a life of petty crime to being a garbage man before finding a “purposeful death” in Syria.[8] British-born Sally Anne Jones’s disordered life featured welfare, sex, rock and roll, and witchcraft before her relationship with much younger hacker Junaid Hussain led her to raving online from Raqqa.[9] The middle-aged Jones was, unusually, much older than many of these recent globalized ISIS recruits who tend to trend even younger than the Al-Qaeda volunteers of the past.[10]

The consequential economic dislocation in much of the West, and the ever increasing competition for jobs, is, no doubt, one factor in the ensuing lethargy of so many young people today. They feel listless, without purpose, without significance, and powerless to do anything to either change their situation or to remedy their problems. They become shut off from the world, and from friends, family, and others who would wish to help. Even if they do have a good job, they may feel as though they are simply living life by going through the motions, skating through, adrift in terms of purpose. And it is in this vulnerable and weakened state that they are susceptible to acedia. Whether it be the belonging and sense of purpose provided by a gang or cult, or escaping from the dull and depressing reality that they see before them via drugs, the potential for self-destructive tendencies are many, with ISIS being just one of the most spectacular ones currently out there.

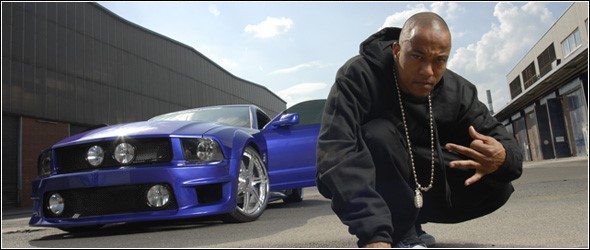

There is a view that youth at risk are being manipulated, that against their better judgment they are pursuing a self-destructive and ruinous path. In this particular war of words, this individual focus may well be the correct cure for acedia. The problem with such a method remains in the difficulty in implementing it on a large scale. Most radicalization is extremely individualized.[11] Inevitably, some people will fall through the cracks and won’t receive the attention they may need. Jihadis provide these individuals with a sense of belonging and a sense of purpose.[12] They offer a spiritual remedy to this spiritual malady, but in this instance the cure is undoubtedly worse than the disease. At least one psychological study of at-risk youth has demonstrated that there is a correlation between lower anxiety and spiritual well-being among at-risk young males.[13] Perhaps this is why ISIS has been relatively successful in recruiting the young and the lost, because they offer some sort of solution to youth suffering from acedia. Certainly, for mediocre German rapper Denis Cuspert (Deso Dogg), ISIS seemed to provide the direction and fulfillment he had so desperately sought.[14]

This is not a problem easily solved by anyone, nor is it something that can or should be fully solved by the state. Instead, it would require a general shift in the mentality and the overall societal beliefs of the West, which is unlikely to occur. Efforts have been made on an individual case-by-case basis; however, much of the responsibility will rest on the family, and on the social environment of the teens and other youths who are viewed as being so easily susceptible to ISIS recruiting methods.[15] In other words, only individual efforts on a larger scale can actually effect any meaningful change.

Young people do fight back all the time. Some Muslims recently highlighted precisely some of those humdrum things of life that can fill one’s time, in order to mock ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi’s latest call to arms.[16] One young convert in Finland went from being a major ISIS propagandist to an open critic.[17]Others have embraced secularism, or alternate forms of spirituality, ranging from the serious to the ridiculous.[18] But unless something changes in the social environment for these at-risk youths, they will continue to be susceptible to radical ideology. It won’t always be the incendiary radical Islamism of today, but may be whatever revolutionary political pathology seems to offer an effectively presented, radical, yet plausible break with conformity.[19] As the popular adage states, “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” and that is exactly the problem with these youths. The fact that Islamism, even the most unapologetically violent versions of it, is “fashionable” provides one very plausible countercultural option.[20]

Because of the ennui, the depression, the acedia which they experience on a day-to-day basis, they hunger for a cause and for a cure to their malaise, and ISIS provides that for them. They have nothing to ground themselves in their current living situation; there is no connection to people or place which prevents them from picking up and leaving for what they believe to be a better prospect. When individuals are raised without a solid worldview, when they don’t truly know what to think about anything, they can be easy prey to those who remain not only convinced of the surety of their cause but of its supposed righteousness as well.

Islamist terrorists exude confidence, sure in their beliefs and confident of the righteousness of their cause – and that confidence can be intoxicating to those who have an absence of absolutes in their personal lives. Even if an individual wants out, once converted and committed so heavily to the extremist cause of ISIS there are few avenues of escape.[21] Acedia, spirituality, emotions, passion, anger, sentimentality, identity, the life of the mind, mental illness – these are all also intangible battlefields in the struggle with the Islamic State and other self-assured Salafi-jihadis.

The original ISIS “caliphate” is slowly being squeezed and deteriorating in its original Iraq/Syrian homeland, but the revolutionary ISIS brand remains powerful, its media apparatus largely intact; it can still attract the confused, the bored, and the idealistic and rebellious. These youth are something like Huxley’s John the Savage in Brave New World: “But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry. I want real danger. I want freedom. I want goodness. I want sin.” Blessed by lives of historically extraordinary comfort in some of the most tolerant societies in existence, some drifting Western youth don’t know exactly what they want, but they deeply want something – and some do find it in the coils of the Islamic State.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

Endnotes:

[1] “The Spiritual Malaise That Haunts Europe,” George Weigel, The Los Angeles Times, May 1, 2005.

[2] John Cassian, Institutes Book X.

[3] “Book review: Acedia & Me A Marriage, Monks, and a Writer’s Life, By Kathleen Norris,” Spiritualityandpractice.com, no date.

[4] “Sunday Book Review: Am I Blue,” Kathryn Harrison, The New York Times, December 21, 2008.

[5] “The Line Between Terrorism And Mental Illness,” Jeet Heer, The New Yorker, October 25, 2014.

[6] “The Short, Violent Life of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi,” Mary Anne Weaver, The Atlantic, July/August 2006.

[7] “ISIS in America, From Retweets to Raqqa,” Center for Cyber and Homeland Security, George Washington University, no date.

[8] “Canadian Killed in Syria Lives On as Pitchman for Jihadis,” Michael S. Schmidt, The New York Times, July 15, 2014.

[9] “Revealed: Benefits mother-of-two from Ken once in all-girl rock band who is now jihadi in Syria – and wants to ‘behead Christians with a blunt knife,'” Chris Greenwood, The Daily Mail, August 31, 2014.

[10] “Role of Youth: Countering Violent Extremism, Promoting Peace,” Scott Atran Ph.D., Psychology Today, May 5, 2015.

[11] “Final Report Of The Task Force On Combating Terrorist And Foreign Fighter Travel,” House Homeland Security Committee, September 2015.

[12] “How to stop ISIS from recruiting American teens,” Lorenzo Vidino and Seamus Hughes, The Washington Post, June 17, 2015.

[13] “Meaning, Purpose, And Religiosity In At-Risk Youth: The Relationship Between Anxiety And Spirituality,” Timothy L. David, Barbara A. Kerr, Sharon E. Robinson Kurpius, Journal of Psychology and Theology, Vol 31(3), 2003.

[14] MEMRI Daily Brief No. 52, Abu Talha Al-Almani – ISIS’s Celebrity Cheerleader, August 13, 2015.

[15] “How to stop ISIS from recruiting American teens,” Lorenzo Vidino and Seamus Hughes, The Washington Post, June 17, 2015.

[16] “Muslims hilariously troll the hell out of ISIS after their call for new jihadists ends up on Twitter,” Tom Boggioni, Raw Story, December 30, 2015.

[17] “The Bullied Finnish Teenager Who Became An ISIS Social Media Kingpin – And Then Got Out,” Sarah Elizabeth Williams, Newsweek, June 5, 2015.

[18] “Elves, Trolls, and the ‘Indigo Child’ – Sometimes, Progressives Replace Religion With Mere Superstition,” David French, National Review, January 11, 2016.

[19] “ISIS is a revolution,” Scott Atran, Aeon, December 15, 2015.

[20] “How can we make Islamism unfashionable?” The Quilliam Foundation, YouTube, August 27, 2015.

[21] “ISIS teen ‘poster girl’ Samra Kesinovic ‘beaten to death’ as she tried to flee the group,” Alexander Sehmer, Independent, November 25, 2015.