Jews and Muslims make peace, but this endangered minority lacks a regional voice.

The announcement that Israel would normalize ties with Muslim-majority Bahrain, Morocco, Sudan and the United Arab Emirates might have been the highlight of an otherwise dismal 2020. Yet these groundbreaking accords still lack one important child of Abraham. Do Near Eastern Christians have a seat at this table? If not, who can help get them there?

Years of international anxiety over the slow demise of Christianity in its ancient homeland hasn’t translated into action. The situation in old bastions like Lebanon, Syria and Iraq is now catastrophic. Egypt, with the largest population of Jesus followers in the region, isn’t much better. That the region’s second most afflicted religious group—after the devastated Yazidis—has gained the least from a long-overdue peace is a painful irony not lost on its persecuted members.

Part of the problem is that the regional hostility being rolled back under the Abraham Accords was never a distinctly Christian problem. The centurylong animus between Muslims, the region’s largest group, and Jews, its oldest Abrahamic population and newest recipient of sovereignty, could only be rectified by Jews and Muslims. The relative lack of Christians in any the four Muslim countries that are part the Abraham Accords—Israel has as many as all of them combined—means that Christians simply haven’t been part of the discussion.

Another thorny problem is the imprisonment of the region’s most dynamic Christian communities in its other geopolitical axis: the resistance bloc controlled by Iran. Tehran’s belligerence is what first seeded the secret Arab-Israeli collaboration that now manifests as open solidarity. Trapped in the northern tier of Mesopotamia, sandwiched between Shiite and Sunni proxies of Iran and Turkey, these Christians dare not whisper a positive word about normalization with Israel.

One final problem is the general lack of Christian sovereignty in the Near East, which precludes them from an independent say on the matter. With the exception of Greece, Armenia and Ethiopia, local Christians—unlike local Jews, who gained independence in 1948—remain subservient players in an Arab conversation that is almost exclusively Muslim.

No population needs peace more than Christians. Yet the largest Abrahamic faith still has no seat at the Abrahamic table. To change that, there seem to be three options.

First, a Christian-majority country in the region could take the lead on its own. The tiny state of Armenia, recently victimized by a combined assault from Turkey and Azerbaijan, is in no position to act boldly. Ethiopia, mired in bloody civil conflict, stands in a similar position. Only Greece—which has recently upgraded its diplomatic footprint across the Near East, especially in Israel and the U.A.E., and retains strong credibility as the metropole of Orthodox Christianity—could pull off such a move. But recent friction between the Orthodox patriarchs of Constantinople and Moscow could make that harder.

Second, Russia, which sees itself as the historic protector of Eastern Christianity, could take advantage of its singular position as regional broker to push Syria or Lebanon into the normalization mix while giving cover from Iranian or Turkish blowback. Russia won’t take such a step unless it serves its interests, in which case the U.S. should only offer cautious support.

The third and best option is for the Biden administration to use its fresh mandate to include the well-being of indigenous Christians in the Abrahamic conversation. The White House has plenty of ways to approach the issue.

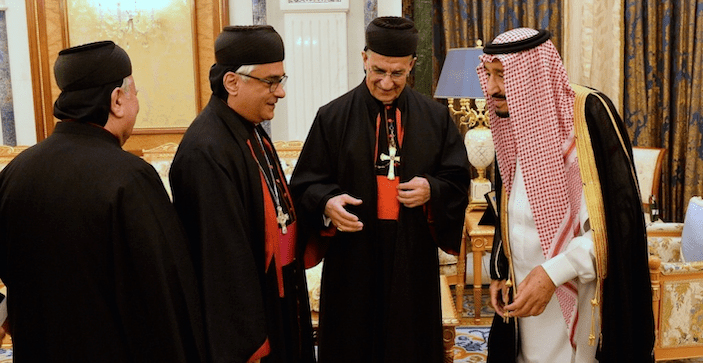

Washington could empower Greece as its local Christian partner. Or it could collaborate with the Holy See to raise Christian concerns from a different angle; Pope Francis ’ visit to Iraq in March presents a good opportunity. The U.S. also could coax a Muslim-majority state already at the table to champion the cause from inside or prod another Muslim-majority state like Saudi Arabia or Egypt to take up the plight of the Christians. Or Mr. Biden and his team could raise the issue directly.

In thinking through America’s role, it would be wise to recall the personality that inspired these accords. Who can forget the image of the noble Hebrew patriarch, incensed by injustice, gathering his retainers to strike back against the mighty kings of Mesopotamia to liberate his kin and Canaanite neighbors? Or his passionate plea to God on behalf of the people of Sodom? True peacemakers are principled and courageous, wielding whatever power they have to secure peace for those who cannot achieve it themselves.

The conditions are ripe, the cause is just, and the opportunity is unprecedented to do right by all the children of Abraham. Working with regional partners, the U.S. can help Christians get a seat at the table.

Mr. Nicholson is president of the Philos Project.