As Protestants prepare to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that the prevailing view among Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe is that they are more similar religiously than they are different. And across a continent that once saw long and bloody religious wars, both Protestants and Catholics now overwhelmingly express willingness to accept each other as neighbors – and even as family members.

As Protestants prepare to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that the prevailing view among Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe is that they are more similar religiously than they are different. And across a continent that once saw long and bloody religious wars, both Protestants and Catholics now overwhelmingly express willingness to accept each other as neighbors – and even as family members.

The survey also shows that one of the major theological controversies of the Protestant Reformation no longer starkly divides rank-and-file Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe. Today, majorities or pluralities of both groups say that faith and good works are necessary to get into heaven – the traditional Catholic position. Fewer people say that faith alone (in Latin, sola fide) leads to salvation, the position that Martin Luther made a central rallying cry of 16th-century Protestant reformers.

Yet differences remain between the two Christian traditions.

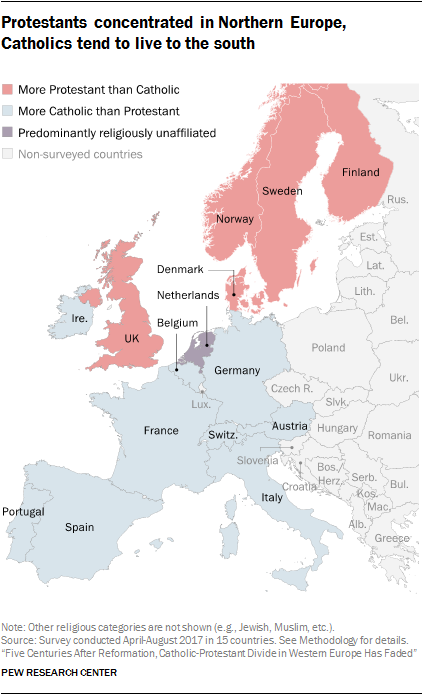

Geographically, Protestants are still concentrated in the north and Catholics in the south of Europe. In many countries, sizable minorities among both Catholics and Protestants (roughly four-in-ten or more Catholics in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy and France and comparable shares of Protestants in Switzerland and the UK) say the two groups are more different religiously than they are similar. And Protestants and Catholics who consider religion to be important in their lives are more likely to take their respective church’s traditional position on salvation compared with those who say religion is less important.

These are among the main findings of a new Pew Research Center survey of 24,599 adults across 15 countries in Western Europe, conducted from April to August 2017 through telephone interviews on both cellphones and landlines. The study, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of a larger effort by Pew Research Center to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many other countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America and the Caribbean; Israel; Central and Eastern Europe; and the United States.

The new surveys are nationally representative, with samples of approximately 1,500 or more respondents in each country, allowing researchers to analyze the opinions of Catholics in 11 countries and of Protestants in eight countries.

Pew Research Center also asked Catholics and Protestants in the U.S. about their opinions on issues related to the Protestant Reformation, including on several questions that were asked in Western Europe as well. The results of the U.S. survey can be found here.

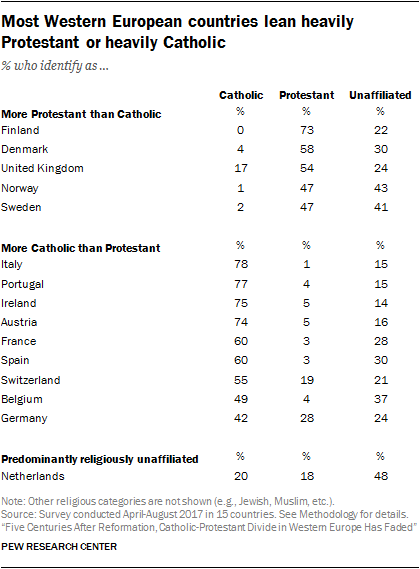

In Western Europe, few countries have an even mix of Protestants and Catholics

Roughly five centuries after the rupture between Protestantism and Catholicism, Western Europe still mostly consists of countries whose populations are either predominantly Catholic or predominantly Protestant.

Roughly five centuries after the rupture between Protestantism and Catholicism, Western Europe still mostly consists of countries whose populations are either predominantly Catholic or predominantly Protestant.

Catholics form the biggest group in nine of the countries surveyed, largely to the south. Protestants are the largest religious group in five countries, all in the north.

Germany – where Luther lived and wrote the list of 95 theological propositions whose publication in 1517 is the event many Protestants commemorate as the beginning of the Reformation – is 42% Catholic, 28% Protestant and 24% religiously unaffiliated. But even Germany is more religiously homogeneous on a regional level, with more Protestants in the north, Catholics in the south and people without a religious affiliation in the east. (See this sidebar for more on the Reformation.)

Many Europeans identify with particular streams of Protestant Christianity rather than with Protestantism as a whole. For example, in Nordic countries, most Protestants identify as Lutheran, while in the UK, most identify as Anglican (or Church of England). Anglicans sometimes describe their church as following a distinctive path that is neither Roman Catholic (since Henry VIII renounced the authority of the pope in 1534) nor wholly Protestant (since the Church of England still views itself as part of the universal or “catholic” church). Nevertheless, for the purposes of this analysis, Anglicans are included in the broadly defined Protestant category, along with the other churches that broke with Rome starting in the 16th century.

The Netherlands is the only country surveyed where a plurality of the adult population (48%) is religiously unaffiliated (identifying as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”). But secularization trends are evident throughout the region. People with no religious affiliation make up substantial shares of the population in several countries, including roughly four-in-ten adults in Norway (43%), Sweden (41%) and Belgium (37%).

In addition, Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe generally show low levels of religious observance.

In addition, Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe generally show low levels of religious observance.

Relatively small percentages of both groups say that they pray daily (medians of 12% of Catholics and 14% of Protestants) and that religion is very important in their lives (13% of Catholics and 12% of Protestants). Attendance at church also is fairly low among both groups, although Catholics are somewhat more likely than Protestants to say they attend church at least once a week.

Dutch Protestants stand out for their relatively high levels of religious observance: About half (51%) say religion is very important in their lives, and a majority (58%) report praying daily. In addition, 43% say they attend church weekly – higher than any Catholic population in Western Europe, and more than four times as high as Protestants in any other country in the region.

Among both Protestants and Catholics, people tend to say both faith and good works are necessary to get into heaven

Since the Protestant Reformation, sola fide, or salvation by “faith alone,” has been a distinguishing feature of Protestant theology. Historically, Protestants have emphasized that people are saved not by their own good works or by penance, but by faith in the sacrifice of Jesus, through which God chose to forgive the sins of all humans. In Luther’s words: “It is faith alone which worthily and sufficiently justifies and saves the person.”1 This was a major departure from the Catholic Church’s emphasis on the need for Christians to make amends for their sins through confession and penance.

Since the Protestant Reformation, sola fide, or salvation by “faith alone,” has been a distinguishing feature of Protestant theology. Historically, Protestants have emphasized that people are saved not by their own good works or by penance, but by faith in the sacrifice of Jesus, through which God chose to forgive the sins of all humans. In Luther’s words: “It is faith alone which worthily and sufficiently justifies and saves the person.”1 This was a major departure from the Catholic Church’s emphasis on the need for Christians to make amends for their sins through confession and penance.

Today, however, Western European Catholic and Protestant laity are no longer starkly divided by this theological issue: More Catholics and Protestants say both faith and good works are necessary to get into heaven than say faith alone leads to salvation. And considerable shares of both groups do not take a clear position on this issue, perhaps reflecting a lack of familiarity with the theological intricacies.

To be sure, Catholics in Western Europe (median of 59%) are more likely than Protestants (median of 47%) to take the traditionally Catholic position that both good deeds and faith in God are necessary for salvation. But even Protestants in every country surveyed except Norway are more likely to say that both elements are necessary for salvation than to take the traditionally Protestant sola fide position. For example, nearly three times as many German Protestants say faith and good works are necessary to get into heaven (61%) as say faith alone is the way to heaven (21%).

To be sure, Catholics in Western Europe (median of 59%) are more likely than Protestants (median of 47%) to take the traditionally Catholic position that both good deeds and faith in God are necessary for salvation. But even Protestants in every country surveyed except Norway are more likely to say that both elements are necessary for salvation than to take the traditionally Protestant sola fide position. For example, nearly three times as many German Protestants say faith and good works are necessary to get into heaven (61%) as say faith alone is the way to heaven (21%).

In fact, in countries that have substantial shares of both Catholic and Protestant populations, only in the Netherlands are Catholics (66%) more likely than Protestants (47%) to say salvation comes from faith and good works. In Germany, Switzerland and the UK, Protestants are just as likely as Catholics – if not more likely – to espouse this traditional Catholic belief.

Among both Catholics and Protestants, those who say religion is “very” or “somewhat” important in their lives are more likely than those who say religion is less important to take their own tradition’s position on salvation.

Religious reformations and religious wars in Europe

If one date must be picked as the starting point of the Protestant Reformation, the conventional choice would be Oct. 31, 1517, when Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and university professor in Wittenberg, Germany, publicly posted a lengthy list of academic arguments against Catholic Church practices. That is the event widely being marked in this year’s 500th anniversary commemorations of the Reformation, which eventually split Western Christianity and led to more than a century of religious warfare across Europe.2

Rather than describing a single Reformation that suddenly divided the Western church into two very different parts, however, many historians now speak of multiple reformations and emphasize the continuities as well as the differences between medieval Catholicism and Protestantism.3 Increasingly, scholars trace the seeds of dissent to church reformers from previous centuries. Prior to Luther (who was born in 1483 and died in 1546), reformers in the Middle Ages included Peter Waldo in northern Italy (circa 1140-1205), John Wycliffe in England (circa 1330-1384) and Jan Hus in what is now the Czech Republic (circa 1370-1415).

Still, Luther and the year 1517 play a pivotal role in the historical narrative. Initially, Luther railed mostly against one Catholic Church practice – the sale of indulgences – which he viewed as a form of corruption.4 Shortly thereafter, he also questioned the integrity of the papacy and the priesthood, arguing that ordinary Christians could have a more direct, unmediated relationship with God. He soon was arguing that popes and grand councils were fallible, and only the Bible was infallible. Pope Leo X excommunicated him, but Luther’s arguments spread throughout Europe and found many echoes and variants. Other reformers active during his lifetime included Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich (1484-1531) and John Calvin in Geneva (1509-1564), whose strands of the Reformation came to be known as Reformed Christianity.

While various reformers and Protestant churches vehemently disagreed on theological issues, several doctrines were adopted by most Protestants, with slight variations. Among the most consequential were “scripture alone” (in Latin, sola scriptura), which held that the Bible, not the accumulated teachings of popes and church councils, was the ultimate source of authority for Christians; “faith alone” (sola fide), which held that salvation cannot be earned through good deeds – much less purchased through indulgences – but rather is freely granted by God to those who have faith in Jesus Christ; and “grace alone” (sola gratia), the idea that salvation comes directly from God to each person, without any intermediaries such as priests, and hence the role of clergy is simply to be ministers in service to others.

In response to Protestantism’s spread, reform efforts within the Catholic Church gained ground, including the founding of the Jesuit order. Many changes followed the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which condemned Protestant teachings as heresies but also sought to clarify Catholic teachings and led to codified versions of the Mass and Catholic breviary (prayer book) that lasted for centuries.

In an era when religion was interwoven with all aspects of life, including politics, the Reformation also set off religious violence across Europe, culminating in the Thirty Years’ War, which lasted from 1618 to 1648. The Treaty of Westphalia finally ended that devastating war and granted minority rights for Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists in many parts of Europe. Still, religiously based wars continued until the early 18th century, and Catholic-Protestant tensions have extended into the modern era in places like Northern Ireland.

Even among more religious Catholics and Protestants, high levels of acceptance of one another

Despite the long history of Catholic-Protestant conflict in the aftermath of the Reformation, Western Europe’s Catholics and Protestants are now very accepting of each other. In every country surveyed, roughly nine-in-ten or more Catholics and Protestants say they are willing to accept members of the other tradition as neighbors. And large majorities of both groups say they would be willing to accept members of the other religious group even as family members.

Despite the long history of Catholic-Protestant conflict in the aftermath of the Reformation, Western Europe’s Catholics and Protestants are now very accepting of each other. In every country surveyed, roughly nine-in-ten or more Catholics and Protestants say they are willing to accept members of the other tradition as neighbors. And large majorities of both groups say they would be willing to accept members of the other religious group even as family members.

In two countries, Ireland and Italy, Catholics who say religion is at least somewhat important in their lives are considerably less likely than those who consider religion less important to say they would be willing to accept Protestants as family members or as neighbors. Still, majorities among both groups say they are willing to accept Protestants into their families. In Ireland, for example, 76% of Catholics for whom religion is very or somewhat important say they would be willing to accept Protestants as family members, compared with 93% of Irish Catholics who say religion is less important in their lives.

Among Protestants, those who are highly religious and less religious are about equally likely to say they would be willing to accept Catholics as neighbors or as family members.

College-educated Catholics are especially willing to accept Protestants as family members and neighbors, though majorities among those with less education also say this.

College-educated Catholics, Protestants more likely than others to know a member of the other faith

In most countries, majorities of Catholics and Protestants say they personally know a member of the other faith, but Protestants living in Nordic countries are less likely to have personal connections with Catholics. For example, just 31% of Finnish Protestants say they know a Catholic, as do roughly half of those living in Denmark (49%) and Sweden (49%). Among Catholics, people in Belgium (39%) and Spain (35%) are the least likely to say they personally know a Protestant.

In most countries, majorities of Catholics and Protestants say they personally know a member of the other faith, but Protestants living in Nordic countries are less likely to have personal connections with Catholics. For example, just 31% of Finnish Protestants say they know a Catholic, as do roughly half of those living in Denmark (49%) and Sweden (49%). Among Catholics, people in Belgium (39%) and Spain (35%) are the least likely to say they personally know a Protestant.

Among both Catholics and Protestants, college-educated adults are more likely than those with less education to say they personally know a member of the other tradition. This is true in all Nordic countries. For example, in Norway, a majority (72%) of Protestants with a college education personally know a Catholic, compared with roughly half (51%) of those who have less education. A similar pattern is seen among Catholics in several countries, including Belgium (53% among college-educated adults vs. 34% among those with less education) and Spain (46% vs. 32%).

More people see Catholics and Protestants as religiously similar

Majorities or pluralities of adults (including Catholics, Protestants and people with no religious affiliation) in all 15 countries surveyed across Western Europe say Catholics and Protestants today are “religiously more similar than they are different.”

Majorities or pluralities of adults (including Catholics, Protestants and people with no religious affiliation) in all 15 countries surveyed across Western Europe say Catholics and Protestants today are “religiously more similar than they are different.”

Still, sizable minorities in several countries see Catholics and Protestants as “religiously more different than they are similar.” Nearly four-in-ten adults take this position in Ireland (39%), Italy (39%) and the United Kingdom (37%).

Generally, people in predominantly Catholic countries are more likely than those elsewhere to say the two groups are religiously different today. In most predominantly Catholic countries surveyed, roughly one-third or more adults take this position. Elsewhere, smaller shares see differences between the two groups, including 18% in Norway and 19% in Sweden. People in predominantly Protestant countries also are somewhat more likely than those in Catholic countries to not take a position on the issue. Among both Catholics and Protestants across the region, the prevailing view is that the two traditions of Western Christianity are more similar than different.

People who say they are personally acquainted with a member of the other Christian tradition are especially likely to see religious similarities between Catholics and Protestants. On the other hand, across the region, those who consider religion important in their lives are more likely than those to whom religion is not important to say the two groups are more different than similar religiously. In Ireland, for example, 43% of those who say religion is very or somewhat important in their lives see the two groups as different, compared with 35% of those who say religion has a less important place in their lives.

Pagination

- Eire, Carlos M.N. 2016. “Reformations: The Early Modern World, 1450-1650.” ↩

- The term “Protestant” did not emerge until 1529, as a result of the Diet of Speyer. At this meeting, Lutheranism was outlawed within the Holy Roman Empire (including modern Germany), but a significant number of cities and regional princes protested this action. This is the protest referred to by the term “Protestant.” Examples of today’s many Protestant denominations include: Anglican/Episcopal, Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist and Presbyterian. (See McGrath, Alister E. 1997. “Christian Theology: An Introduction.”) ↩

- Eire, Carlos M.N. 2016. “Reformations: The Early Modern World, 1450-1650.” ↩

- Luther’s 95 Theses focused on indulgences, something many in the Catholic Church had wanted to reform. Indulgences were payments made to the church by sinners both to avoid time in purgatory and to demonstrate thankfulness to God and the church after they had been forgiven. Over time, however, the public began to view indulgences as a means of buying forgiveness. Luther argued that financial payments did not help people escape purgatory, and that forgiveness was based solely on a direct relationship between God and sinner. (See McGrath, Alister E. 1997. “Christian Theology: An Introduction”; and Marshall, Peter. 2009. “The Reformation: A Very Short Introduction.”) ↩