If you blinked, you would have missed it.

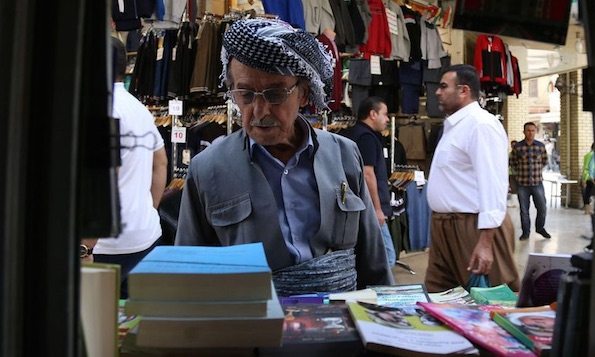

For less than three weeks, it looked as if the Kurds might have their own independent country. The Kurds control a mountainous area in northern Iraq and since the British occupation in 1920 they have been pushing for their own independent country.

Last month, the Kurds held a referendum in which those who turned out voted 92 per cent in favour of independence. Cue cheers and celebrations in the Kurdish Highlands of Iraq.

It was not a popular move among Kurdish neighbours. In a rare display of unanimity, the Iraqi, Iranian and Turkish governments all condemned the vote. Even the Americans, normally the Kurds strongest allies, said publicly that they would not support the referendum results.

It is easy to sympathize with the Americans. This is a complicated situation in a volatile region and the Kurds are like the Scottish highlanders, without their customary restraint.

It is also easy to sympathize with the Kurds, for unlike the highlanders, who only had to deal with the English, the Kurds have to manage their survival in a homeland divided between the four regional powers of Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria.

However, the Kurds, like the highlanders, also have a set of inter-clan rivalries that make the Campbells and McDonalds look like Quaker vegetarians. In the 1990s, one powerful Kurdish leader actively aided Saddam Hussein in his fight against another Kurdish clan.

However, since the American overthrow of Saddam in 2003, the Kurds have been trying to do two things: First is paper over any clan rivalries to convince the outside world that they are one happy ethnic group. They might have had more success with this effort, if their current president, Masoud Barzani – the man who allied himself to Saddam – had not clung illegally to power since 2015.

The second thing the Kurds tried to do is take control of the Iraqi city of Kirkuk.

Kirkuk the Seat of Power

Kirkuk is one of the great oil centres of the world. Stick a fork into the flat plains around the city and you can expect a black gusher of liquid money to start flowing. If the Kurds could control Kirkuk, they could have a proper financial basis for independence. Their highlands are good for grazing sheep and farming but little else.

The problem was that Kirkuk has been part of Iraq for millennia. It was a multi-cultural city with large communities of Iraqi Christians, Turks, Iranian-supporting Shia, Saddam-loyal Sunni and Kurds.

Sooner than you could say,”not on my kilt,” Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi moved troops into Kirkuk. They deposed the Kurdish city governor and seized control of the oil fields and their revenue.

Winners and Losers

The big winner in this battle is the Iraqi central government. In one year, it has successfully taken on the two largest forces pushing for the dismantlement of their country: ISIL and the Kurds.

The other massive winner is Russia. Last summer, its biggest oil and gas company, Rosneft, signed a multi-billion-dollar pipeline deal with the Kurdish government. Now the Russians have offered themselves as peace brokers between the Iraqi government and the Kurds. Of all the unforeseen consequences of the U.S. invasion of Iraq – the destruction of Iraq’s Christian community, the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, Iran’s growing power – the expanding influence of Russia inside the Middle East is the biggest.

All these geopolitical games affect Canada. For the last few years, our military has been playing a flirtatious game of footsie with the Kurds. Our soldiers have been “training” the Kurdish forces. In fact, our Canadian soldiers were so close that some of them wore Kurdish badges and identification on their uniforms. This past June, a Canadian “trainer” achieved the longest sniper kill in the history of warfare when officially “not fighting” beside the Kurds in the battle outside of Mosul.

It raises the question: If more serious fighting begins in Kurdistan, which side will our troops be on? At the moment, the soldiers we have trained will be fighting with Russian money against the Iraqi national army allied to the U.S. Once again, its strange times and strange allies in the Middle East.