New Islamist rulers are trying to destroy the drug empire that financed the former regime in Damascus. Can they succeed?

Ahmed’s platoon began melting away last December once they realised the Islamist rebels they had long feared had overrun the Syrian capital and ousted the dictator Bashar al-Assad.

Fearing he would be tortured and killed if seen in his fatigues, he stripped off and did what he always did during stressful times in the army: he smoked a cigarette and raided his emergency drug stash for half a tiny white pill of captagon, a highly addictive amphetamine-like stimulant.

“It gave me the burst of energy I needed to walk several hours to get home. It also gave me the courage — or, actually, delusion — to think I could fight off any of the rebels if I needed to,” Ahmed, a pseudonym, said with a wry laugh. “I’ve never been so grateful for drugs in my entire life.”

There was no shortage of captagon under Assad, who during the 14-year civil war financed his regime with a $5bn-a-year industry that turned Syria into one of the world’s most prolific narco-states.

But while Ahmed still pops the occasional pill in Damascus nightclubs, Syria has since that December day seen a startling reversal: a sweeping war on drugs as new President Ahmed al-Sharaa seeks to dismantle the empire Assad left behind.

“Syria became a major factory for captagon,” Sharaa declared in Damascus’s Umayyad Mosque upon taking power. “And today Syria is being cleansed of it, by the grace of Almighty God.”

Results have been swift. Production and trafficking have dropped by as much as 80 per cent, according to drug dealers, law enforcement, regional government officials and researchers, as authorities busted captagon labs in former regime strongholds and destroyed millions of pills.

But as reformist governments in Latin America and elsewhere have learned — and Sharaa’s under-resourced government is finding out — starting a war on drugs is easier than winning one.

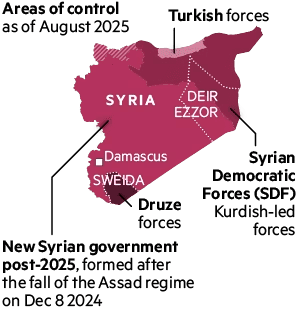

While industrial-scale production has slowed, producers, smugglers and distributors have fought back, evading arrest, clashing with authorities and exploiting power vacuums as the new government struggles to consolidate control across the fractured country’s hinterlands.

Demand, too, has not gone anywhere. Cheap versions of captagon, still readily available despite mounting supply shortages, can sell for about 30 cents per pill in Damascus while higher-quality versions can fetch about 30 times more in Jordan, Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates.

“After the Assad regime fell, there was an expectation among some — even proclamations — that the captagon trade was ‘done,’” said Caroline Rose, who heads the Captagon Trade Project from New Lines Institute, a think-tank. “But if the last eight months in post-regime Syria have proven anything, it’s that this illicit drug trade is far from over.”

Captagon was first produced by a German pharmaceutical company in the 1960s to treat conditions including depression. Long since banned, it took off in the Middle East, used in Gulf Arab states by partygoers or shift workers, before finding its way to Syria’s battlefields, where its euphoric intensity fuelled fighters for days at a time.

For the Assad regime, debilitated by sanctions and conflict, this created an opportunity. Thanks in part to its pharmaceutical industry and access to the Mediterranean, Syria became a regional hub, with the regime providing easy imports of raw materials and effective immunity for producers.

Assad, his relatives and associates deepened their involvement. The former president’s brother Maher, who headed the Syrian army’s notoriously brutal Fourth Division, was largely responsible for the illicit revenue streams to finance the war effort.

Ahmed said the regime’s ties to captagon were so deep that dealing was rampant in the army and pro-Assad militias. When not selling to soldiers, he said, commanding officers would provide pills free of charge or lace their tea and cakes with captagon ahead of operations, or to help soldiers living on paltry rations stave off hunger.

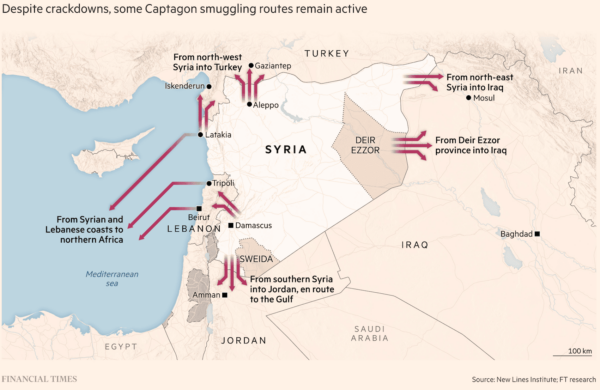

The relentless flow of drugs out of Syria under Assad infuriated his neighbours, particularly Gulf Arab states, who complained about the damaging impact of captagon on their societies. Syrian-made pills turned up everywhere from Riyadh raves to European ports, with shipments seized as far afield as Hong Kong and Venezuela.

For Sharaa and his former rebel movement Hayat Tahrir al-Sham — Islamists ideologically opposed to the drug and what they saw as the regime’s moral bankruptcy — cracking down was both a duty and a means to improve Syria’s standing.

The new authorities and their nascent counter-narcotics forces have conducted widely publicised raids across the country.

Since December, they have uncovered industrial-scale manufacturing facilities linked to the former regime and first family, like the Mezzeh military airport in Damascus and villas owned by Maher and his frontmen.

Authorities seized more than 200mn pills between January and August 2025, according to the New Lines’ captagon project, 20 times the amount Assad’s forces seized in all of 2024.

Units, which can include officers who used to work in counter-narcotics under Assad as well as new recruits, now operate throughout the country, particularly in border areas near Lebanon, Jordan or Iraq.

Ahmed described how his main dealer in Damascus was recently arrested by a neighbour, a former rebel-turned-counter-narcotics official, who returned to Damascus in December.

“After initially letting him go with several warnings, the rebel eventually raided the dealer’s apartment,” Ahmed said, “marched him out into the building courtyard handcuffed, forced him to his knees surrounded by bags of drugs and humiliated him in front of all of the neighbours, before carting him off to jail.”

The new forces’ biggest coup came in June, when Syrian officers lured Wassim al-Assad, the former president’s cousin who was placed on sanctions internationally for his role in the trade, back to Syria in a sting operation.

Returning from Lebanon, where he had been sheltered by militant group Hizbollah, Wassim was arrested trying to retrieve mounds of cash and gold bars stashed near the border, Syrian security officials said.

Yet, in Syria as elsewhere, drug lords are often a step ahead.

The new counter-narcotics units have clashed with regime loyalists and people with ties to Hizbollah and Iran-backed militia groups who want to maintain their foothold in the trade.

According to an interior ministry official in eastern Deir Ezzor province, the main security threat is no longer Isis militants but the Iraqi Shia militias still operating captagon networks on both sides of the border.

“In every captagon facility we bust, we’re finding so many weapons,” he said.

In a dusty corner of southern Sweida province, a short distance from the Jordanian border, long-standing criminal networks affiliated with the Assad regime or Bedouin Arab tribes have kept the trade going.

Traffickers have survived in part because they operate in regions — including the Kurdish-controlled north-east — where the new government has been unable to take control, with Sharaa’s forces recently forced to withdraw from Sweida after sectarian clashes.

Small commercial drones, rockets emptied of explosives and more recently remote-controlled balloons — all laden with pills — whizz across the frontier to Jordan, from where their contents are sold on to Gulf Arab states.

Some shipments are intercepted, and locals say there are far fewer trafficking attempts than there used to be. “We used to see dozens of cars drive through our sleepy village and 10 attempts a day,” one border area resident said. “Now we can go two or three days without seeing a single attempt.”

But it is not hard to recruit smugglers in Sweida, where jobs are few and poverty is rife, smugglers say. Young men are lured in with offers to make thousands of dollars carrying a bag of 25-30kg of captagon, worth at least $25,000, across the frontier.

Some border guards in Syria — known to have been paid off to allow the trade — have stayed in place due to personnel shortages, according to smugglers, law enforcement officials and analysts.

“We would know which border guards were in on it and would make sure to only deal with them,” a former smuggler said. “Those same guys are still turning a blind eye.”

While authorities might eventually clean their ranks of corrupt soldiers and officers, the lure of quick riches could pull new recruits too.

One undercover officer in the counter-narcotics forces in Qalamoun, a border area with Lebanon, said they had struggled for months to investigate one of the biggest known traders who relocated labs to Lebanon but still operated smuggling routes through Syria.

Eventually, he came to suspect that officers within his own unit were playing a double game. “We can’t get close,” the officer said. “He knows when raids are coming . . . Some people in our unit must be warning him.”

Up against an entrenched trade, smugglers and locals told the FT authorities had turned to increasingly harsh methods, with one Jordanian official saying the country will use “proportionate and disproportionate” force to repel the trade.

“They used to never kill us, but now, they will shoot at whoever approaches the border at night,” the former smuggler said of the Jordanian border guards.

Ultimately, far from the frontiers, Syrians are still reckoning with the costs of Assad’s drug empire.

The country has only four addiction treatment facilities. Hospitals mostly provide for only a rudimentary two-week withdrawal period, with no rehabilitation programme.

It is “nowhere near enough to treat the extent of the problem in Syria”, said Dr Ghamdi Faral, the director of Ibn Rushd hospital, which houses an addiction facility in Damascus. “But the state can barely afford that as it is.”

Ghamdi said that, with captagon shortages driving up prices across the country, many users had turned to cheaper and more dangerous substitutes such as crystal meth.

This includes Ahmed, whose own crystal meth use led to him having several teeth replaced. While the high was more intense, he would rather stick to captagon — which he now uses to party rather than survive military conscription — while he can still get it.

“The message is clear: there is no tolerance for drugs in new Syria,” Ahmed said. “But after everything we’ve been through, that’s not enough to stop us.”

Additional reporting by Hussam Hammoud Data visualisation by Aditi Bhandari