Even before a new American president is inaugurated, some critics are hyperventilating and making sweeping statements about the new administration and Islam.[1] At least some of these analyses seem to have a partisan bias and miss the deep anger about the U.S. and the policies of the Obama administration that are existing already in the Sunni Arab Muslim Middle East, ground zero for ISIS and ALQA. After an Iran deal and after the horrors of Syria, many Sunni Arab Muslims have seen the current U.S. government as a willing or oblivious partner to their enemies. As one influential Gulf Arab editor recently noted after the U.S. presidential election, “no one will weep about his [Obama’s] White House departure!”[2]

The larger debate about where exactly to draw the line on extremism and what exactly to focus on is legitimate, and one that goes back years and is grounded in a basic, fateful question: Is Islamism per se a favorable environment for jihadi radicalization or not? Is “non-violent” Islamism a gateway drug to Jihadism or is it a vaccine? As a student of the Middle East region for most of my life, living and working there for decades, this is a question I have seen many wrestle with often.

So when we look at the basic question, we should begin by admitting that the facts are complicated and that when it comes to human beings, to matters of love and hate, belief and unbelief, violence and non-violence, it is always complicated. Some have sought to excuse or coddle radical Islam, others to demonize Islam or to demonize religion in general. But one never forget that the deadliest ideologies of the past century in terms of millions of dead were neither Islamic nor religious – but were actually secular or atheistic ideologies, those of National Socialism and of Communism.

Like National Socialism and Communism, Islamism is a modern ideology too, and often conflated with other things. This is not about being a practicing Muslim or a conservative or traditional Muslim. Muslim reformer Maajid Nawaz defines Islamism as the effort to “impose Islam on any society, while jihadism is the effort to impose it by the use of violence.”[3] In both its Ikhwanist/Muslim Brotherhood or Salafi/Salafi-jihadi incarnations, this is a modern – even 20th century – ideology that pays lip service to personal piety or religious conservatism but is about political power expressed through a specific political and religious reading drawn from some texts and examples of formative Islam.

In my view, an Islamist worldview sets the stage for radicalization into jihadism; it can often be a type of gateway drug. This is despite the fact that many types of Islamism and jihadism across the spectrum bitterly contend against each other, a fact that one can see, for example, in the ISIS condemnation of some very extremist Salafi clerics – and of Al-Qaeda itself – who happen to be against the Islamic State.

Certainly not all manifestations of this quarrelling family of Islamist ideologies are equally dangerous at the same time, but all of them do clash to a greater or lesser extent with today’s seemingly fraying liberal world order. But so is also the case with rising (non-Muslim) authoritarian powers, and such was also the case with events like the fall of Aleppo.[4]

This Islamist vision, which can set the stage for further extremism, is often replete with a fervent “chosen trauma” which includes a certain worldview about the self and the world around us.[5] Both Islamism and jihadism set themselves apart in sharp contradistinction to “the Other.” Analyst Nervana Mahmoud has described the challenge within the context of Egypt as follows: “Islamism indoctrinates followers to behave and think as an oppressed minority, unfairly targeted by others, while portraying the real minorities, such as Copts, as powerful, privileged, well-connected groups.”[6] Here you have the crux of the worldview, an ideology which revels both in self-pity and in victimizing others.

Radicalization is accompanied by a specific, narrowed, and detailed take on the key issues of violence, hatred, loyalty, and the view of outsiders expressed in the language of religion. This religious worldview is what we call in Arabic “Aqeeda,” which one Islamist website describes as “those matters which are believed in, with certainty and conviction, in one’s heart and soul. They are not tainted with any doubt or uncertainty… in Islam, Aqeedah is the matter of knowledge. The Muslim must believe in his heart and have faith and conviction, with no doubts or misgivings, because Allah has told him about Aqeedah in His Book and via His Revelations to His Messenger.”[7]

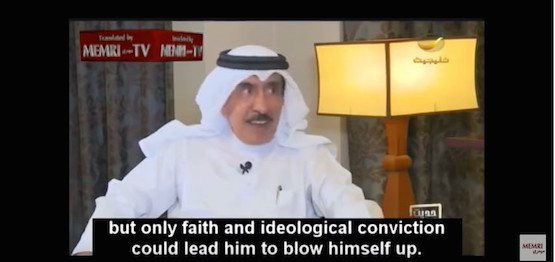

The great Qatari humanistic scholar Dr. Abd Al-Hamid Al-Ansari, former dean of the School of Sharia at Qatar University, with a Ph.D. in Sharia from Al-Azhar, is someone we have featured frequently in our coverage of Muslim reformers and liberals.[8] Rather than Westerners opining on such issues, I thought it would be interesting to look at the issue through his eyes. He defined the challenge of extremism this way in a June 2016 interview on Rotana Khalijiyya TV: “Terrorism is an idea (fikr), it is an aqeeda, it is an ideology… to have something that would turn you into a human bomb, this is not because of oppression or poverty but because of an ideology which is able to take you over.”[9]

Al-Ansari describes the aggressive mindset, psychology of hate and violent behavior that characterizes the jihadi terrorist. The first step is, he believes, to “sow hatred of the Other” which he sees happening in a suitable environment of extremist religious discourse. Not all Islamist extremists are terrorists, he cautions, but all of the jihadis are extremists.

Al-Ansari focuses on three areas of Islamist discourse, in particular where they support and undergird the call for terrorist action. This is especially interesting as he is talking about extremism within majority Muslim societies that are already quite conservative. The first area is Jihad. He makes the case – which many make, of course – that jihad is not just fighting in battle. “My Jihad may be in education and yours may be in media,” so the concept of jihad is not just violence.

Secondly, he makes the case that the Jihad described in the Koran was of a specific time, place and circumstance. And thirdly, he states an obvious history lesson that is all too often forgotten (or willfully ignored) by both the jihadis of today and by many non-specialist critics of Islam as well: For almost all of Islamic history, from the time of Muhammad until the 20th century, “Jihad” has meant conventional war, war between states or governments, and was something declared by a Ruler, by the Sultan or the Caliph or the Amir. It was not some sort of individual duty for someone to take on according to their own views of the situation.

It was Sayyid Qutub in the 1960s[10]and his popularizer Muhammad Abdel Salam Faraj in the late 1970s that spread the idea that Jihad was a “neglected – individual – duty” instead of something done by governments or by communities.[11] But as compelling as this argument for Jihad has been and as widespread as it is among Islamists, it is an innovation, something very new within Islamic history.

The second area that Dr. Al-Ansari focuses on is the Islamist concept of Al-Wala wal-Bara (loyalty and disavowal) – the idea that a Muslim must reject non-Muslim government and give his loyalty only to Islam, meaning those organizations deemed to be sufficiently “Islamic.” In this concept, the individual is forced into a position of choosing between his religion or his nationality or citizenship. This is a widespread Islamist concept that would, if believed, turn any and every Muslim citizen not living in a country ruled by an “authentic” Islamic government into a potential traitor, into a ticking time bomb.

In this worldview, a Muslim – for example – born in America and bearing U.S. citizenship has no loyalty to the land of his birth, to a state, to elected representatives, and to the system of law and order that exists there, let alone to a flag or to a president – to none of that, but not only must he not be loyal to it but must reject it, he must be actively and violently opposed to such rule. This is a seductive argument to make, especially to young men, second generation immigrants already confused about their identity.

The third key area that Al-Ansari highlights is the well-known concept of takfir, the process of declaring someone an infidel. I wrote a whole study of this only some months ago for MEMRI on how ubiquitous the concept is among NON-Jihadist Islamists.[12] This is part of what the Qatari professor sees as an essential part of sowing the seeds of hatred, “that the Other is not fit to live, that the Other is a Kafir, that he is an enemy who is targeting me… this constant discourse that we are constantly being targeted is the beginning of hatred.”[13]

So when we talk of Islamism’s causal role in the radicalization process, we have some very clear questions that we can ask that can provide us an objective sense on whether or not a suitable ideological environment exists for extremism. What is this particular Islamism’s concept of Jihad? What is its concept of Al-Wala wal-Bara and how are questions of citizenship and loyalty seen? How does it see the Other, the non-Muslim, the non-practicing Muslim, the heterodox Muslim? All those are potentially deadly categories inherent in this litany of Kuffar, Mushrikeen, Rafidah, Murtadd.[14] What precisely should be the fate of someone who should fall into these categories?

In these answers lies at least some clarity removed from the hysteria which all too often accompanies the subject.

More often than not, we will see very little difference indeed between the Islamist view and the jihadi view on many of these issues; the only difference may be the actual presence of violence, but the intellectual framework, the environment of hatred and alienation, is intact in a way that, absent a very specific counter argument, will provide the justification for acts of violence when and where they can be ignited.

This is why it is so important for governments and individuals of good will to understand the ideological dimensions of the struggle and to factor them into the overall program of countering extremism. This is not to ignore a whole range of other contributing factors – individual, economic and social – but to place the ideological challenge within its full spectrum context and to realize that there will always some sort of excuse, as Al-Ansari noted:

“It is always a pretext. They also talk about Western injustices, about Israel. They say: ‘Look at the annihilation of Muslims. America and the West are annihilating the Muslims in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the [Muslims] are wreaking vengeance on the West. [Terrorism] is a reaction.’ This is not true. It’s an illusion. Terrorism is an action, not a reaction. The fanatic ideology has existed among us since the days of the Kharijites.”

The Qatari professor believes that interpreting the foundational texts of Islam in a “progressive, humanistic” way is one path towards fighting extremism. Another part of that path is promoting education that nurtures the whole person in being more open and enlightened, including by promoting learning in life-affirming fields like the arts and music.[15]

A humanistic and tolerant worldview that is appealing to youth at an early age is clearly an important approach.[16] Rescuing Islamic history from the straitjacket of the extremists is another key element. Certainly, understanding the role that Islamist concepts of war, loyalty and the treatment of the (non-Muslim) “Other” play into the radicalization process is also a useful part of the anti-terrorist toolkit.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

[1] The Washington Post, December 11, 2016.

[2] MEMRI Special Dispatch No. 6680, Senior Saudi Journalist Turki Al-Dakhil: Trump Will Be Good For Gulf States, November 16, 2016.

[3] Quilliamfoundation.org, November 30, 2012.

[4] Timep.org, July 10, 2016.

[5] Vamikvolkan.com, June 10, 2004.

[6] Nervana1.org, December 13, 2016.

[7] Islamqa.info/en/951, December 20, 2016.

[8] NYsun.com, May 23, 2007.

[9] MEMRI TV Clip #5522, Qatari Prof. Abd Al-Hamid Al-Ansari Analyzes The Ideological Roots Of Terrorism: Something Is Wrong In Our Cultural Order, June 1, 2016.

[10] Berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/quotes/sayyid-qutb-on-jihad-and-mission, January 1, 1964.

[11] Nationalinterest.org, May 5, 2004.

[12] MEMRI Daily Brief No. 98, ‘Kufr’ And The Language Of Hate, July 25, 2016.

[13] Youtube.com/watch?v=gbvyKOfN9gw&t=252s , published June 3, 2016. Accessed December 20, 2016.

[14] MEMRI Daily Brief No. 49, Islamic Words That Kill, July 23, 2015.

[15] MEMRI TV Clip #5649, Qatari Professor Abd Al-Hamid Al-Ansari: Terrorism Is Not A Reaction To Political Injustices, August 3, 2016.

[16] MEMRI Special Dispatch No. 6702, Qatari Writer: Religious Extremism’s Roots Are In Muslim Society, Not External Elements, December 6, 2016.