Secret KGB documents reveal just how deeply involved the Soviet Union was in the spilling of Israeli blood. The Russian spy agency provided Palestinian terror organizations with funds, training and arms, running agents like ‘Krotov’ – aka Mahmoud Abbas, ‘Aref’ – or Yasser Arafat, and ‘Nationalist,’ who was behind several plane hijackings long before 9/11.

The covert operation was codenamed “Vostok” (east in Russian). The ship’s crew was ordered not to ask any questions, not to open the cargo crates, and most definitely not to try to talk to the mysterious man who came on board. His name was Sergey Grankin and he was a major in Department V, a top secret unit of the KGB which is responsible for contact with “liberation organizations” across the world.Grankin, then 35 years old, was working on behalf, and under the close supervision, of the Soviet intelligence services’ omnipotent boss—KGB chairman Yuri Andropov.

As the ship was nearing Aden, the captain received the coordinates for the late-night rendezvous at the heart of the gulf, somewhere on the way between Yemen and Somalia. Around 9pm, the ship slowed down and its lights went out. All of a sudden, a far-away flashing light appeared which seemed to be coming nearer and nearer still. It was a rotating red signal lamp placed on the mast of a civilian cargo ship.

The two vessels exchanged a series of previously-agreed-upon signals, following which the ship unloaded the cargo crates onto rubber boats that made their way to the civilian ship. After several trips back and forth, Grankin made his way to the second vessel as well.

Upon boarding the civilian cargo vessel, Grankin began opening several of the crates. Despite the complete darkness surrounding him, peeking from the crates he could see guns, machine guns, RPG launchers, grenades, sniper rifles and the crowning glory—landmines and roadside charges with remote detonators, the height of technology at the time.

Grankin turned to a Middle Eastern-looking man who was standing on the deck not far from him and appeared to be the boss on the ship, and warmly shook his hand. The man was known in the KGB as “Nationalist,” but his real name had already gained notoriety throughout the West: It was Wadi Haddad, the head of operations at the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). At the time, he was one of the most infamous and dangerous terrorists in the world, and was later believed to be at the top of the Israeli Mossad’s hit list for over a decade.

The massive arms shipment, which included sophisticated weapons the Russians hadn’t even provided the members of the Warsaw Pact, was to be used by Haddad for a series of terror attacks, assassinations and abductions all over the world.

Half a year after that late-night meeting at sea, on September 6, 1970, PFLP terrorists armed with the weapons from these crates hijacked four jet airliners bound for New York City and one bound for London. The hijacking of one of the planes, El Al flight 219 from Amsterdam, was foiled thanks to undercover Shin Bet air marshals who shot terrorist Patrick Argüello dead and managed to subdue and arrest his partner Leila Khaled. Two other hijackers were prevented from boarding that flight, and instead hijacked Pan Am Flight 93. The four planes were flown to Jordan, where they were forced to land at Dawson’s Field, a remote desert airstrip near Zarka, formerly a British Royal Air Force base.

Thirty-one years before the 9/11 terror attacks, Haddad had already managed to carry out an attack that included the simultaneous hijacking of several jet airliners. This attack was one of the triggers of Jordan’s big confrontation against terror organizations—known as “Black September”—and changed the course of history in the Middle East.

Later, the Russian weapons were used to murder Americans in Lebanon and Israelis in Europe and to blow up oil reservoirs. They were also used in an attempt to sink an Israeli tanker in the Red Sea and were meant to be used in a planned large-scale attack on the Israel Diamond Exchange in Ramat Gan. Several of the guns from those crates were also used by the hijackers of an Air France plane to Entebbe in June 1976.

This shipment was yet another link in the long chain of deep cooperation between the Eastern Bloc’s intelligence services, led by the KGB, and Palestinian terror organizations.

Classified KGB documents reveal that the Soviet spy agency aided Haddad and his men by providing them with training, funding and arms, as well as help in the preparations for specific attacks. In other instances, the KGB itself initiated attacks that were carried out by Haddad and his men. And Haddad’s terror organization was not the only one operated by Moscow.

***

Chapter one of “The KGB’s Middle East Files,” a special series of articles which brings to light information mined from some 6,000 KGB documents smuggled to the West in the early 1990s, recounted the story of how Vasili Mitrokhin used his senior position at the spy agency’s archive to copy the top secret documents—with the Soviets being none the wiser.

These documents helped expose some 1,000 KGB agents across the world and uncover countless covert spy operations. In addition, two books were published about them by Prof. Christopher Andrew in cooperation with Mitrokhin himself. Nevertheless, only part of the information they contain actually made it to Israel. In fact, much in this vast trove of information about the KGB’s operations in the Jewish state remains secret.

The Mitrokhin documents have recently been moved to Churchill College in Cambridge. Over the past six months, we’ve been working on sifting through them, translating them, and cross-referencing the material with other available information and sources.

Chapter one of this series included a list of agents that—according to the Mitrokhin documents—operated in Israel, among them Knesset members, media personalities, senior engineers working on sensitive projects and officers who managed to infiltrate the top echelons of the IDF.

But this was only part of the story. As we delved deeper into the secrets Mitrokhin left behind, we discerned another Soviet strategy taking shape: Not content with merely infiltrating centers of power in Israel and gathering intelligence on the Jewish state, the KGB also forged extensive ties with Palestinian terror organizations, greatly abetting their activities. In fact, the Mitrokhin documents show that the Soviet Union waged a kind of “shadow war” with Israel (and the US) for years, using those terror groups as their proxies.

For many years, Israel’s intelligence services suspected that the KGB was aiding at least some of the Palestinian terror organizations, but these were normally general suspicions, which were not necessarily based on quality or reliable intelligence. The Mitrokhin archives prove just how deep the cooperation between the USSR and the Palestinian terror organizations was, and what a bloody cost it exacted from the world in general—and especially from Israelis.

‘Give me missiles’

The genesis of the KGB’s developing ties with Palestinian terror organizations can be traced back to the end of the 1960s. The Soviet spy agency had code names for the different factions making up the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): Fatah, the main movement led by Yasser Arafat, was dubbed “Kabinet” (cabinet); the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) received the name “Khutor” (which means a small village or a farm in Russian); the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) was named “Shkola” (a school in Russian); and Ahmad Jibril’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC) was dubbed “Blindage” (a fortified wooden military structure).

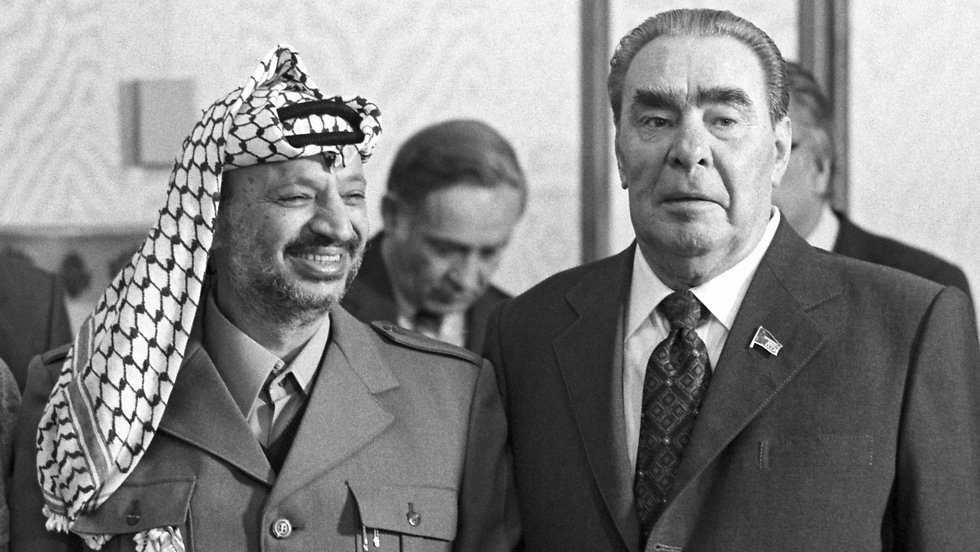

Arafat himself received the codename “Aref,” but the Russians weren’t particularly impressed with him at first. The Mitrokhin archive includes a memo that notes: “Aref only keeps promises that benefit him. The information he provides is very laconic and only serves to promote his own interests.” The KGB also questioned many of the biographical details Arafat provided them with—his past as a combat soldier, his birth place, and more. Despite this, the KGB appointed a senior liaison officer named Vasili Samoylenko to “cultivate” the Fatah leader.

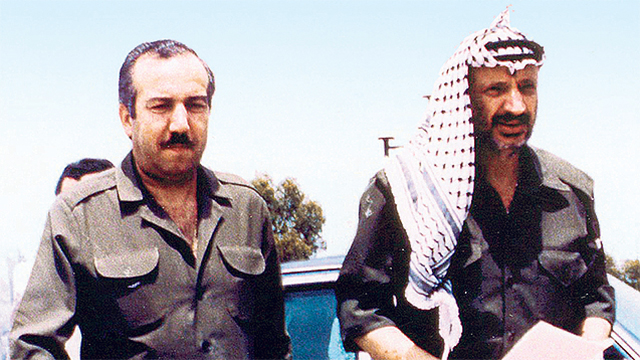

Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat with Abu Jihad (Photo: Reuters)

At the same time, the KGB planted an agent in the office of Hani al-Hassan, one of Arafat’s close advisors, who later went on to become a senior official in the Palestinian Authority. This agent, who according to the Mitrokhin documents was codenamed “Gidar,” was Rafat Abu Auon, who was recruited in 1968 and served in the KGB for many years henceforth.

But the interest in Fatah and Arafat was limited at that point. The Russians were a lot more interested in the PLO’s other factions, particularly George Habash’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

“One of the reasons for that is the Marxist–Leninist ideology of Habash’s men,” explains Prof. Christopher Andrew, one of the world’s foremost historians researching intelligence services, whose second book about the Mitrokhin documents includes an extensive chapter on the KGB’s activity in the Middle East.

Habash may have been the head of the PFLP, but it was his deputy, Dr. Wadi Haddad—a Christian Arab from Safed and a pediatrician like his boss—who had the brilliant operational mind. Haddad greatly improved upon a form of terrorism that was still in its infancy at the time—hijacking planes—and understood the power of international media coverage that such an attack garners.

He was the mastermind behind the hijacking of an El Al plane to Algeria in July 1968, which ended with the release of the passengers in return for 16 Palestinian prisoners and was considered by the Palestinians as a great success.

He was also behind the hijacking of the Tel Aviv-bound TWA Flight 840 to Damascus in August 1969, which received unprecedented media coverage. That hijacking ended with the passengers being released and its perpetrators being arrested by Syrian authorities immediately upon the plane’s landing in Damascus, but not before they managed to blow up the empty plane. One of the hijackers was Haddad’s infamous protégé Leila Khaled, who also took part in many other terror attacks. During the flight to Damascus, Khaled entered the cockpit, put a gun to the captain’s head and ordered him to “fly over Haifa, over my city, over Palestine—where they won’t let me return.”

According to Yigal Pressler, who at the time was a senior officer in Military Intelligence entrusted with identifying targets for assassination, “We called Wadi Haddad the ‘Palestinian Carlos’ (after infamous terrorist Carlos the Jackal). He was as cunning as a snake and very deadly. We’ve searched for him everywhere.”

Israel’s intelligence community fought Haddad for years, but the Mitrokhin documents reveal it wasn’t just dealing with a talented, diabolical Palestinian terrorist, but was also up against the massive might of the KGB that backed him.

So impressed were the Russians with Haddad’s operational abilities, that shortly after the hijackings of those planes the KGB once again sought to make use of his talents.

The Mitrokhin documents don’t include Haddad’s exact date of recruitment, but in late 1969, KGB chief Andropov wrote a top secret report ( Russian original) to then-Soviet Union leader Leonid Brezhnev, telling him about Haddad’s recruitment under the codename “Nationalist.”

Andropov detailed to his boss the advantages of the new intelligence asset: “The nature of our relations with W. Haddad allows us a degree of control over the activities of the PLFP’s external operations section, to exercise an influence favorable to the USSR, and also to reach some of our own aims, through the activities of the PLFP while observing the necessary secrecy.”

Andropov described the kind of operations Haddad could carry out for Soviet interests as “active measures.” According to the KGB’s internal lexicon—also included in the Mitrokhin documents—active measures are “operations carried out by agents or fighters, meant … to solve international problems, deceive rivals, weaken their status and disrupt their ability to successfully execute hostile (to the Soviet Union) plans.”

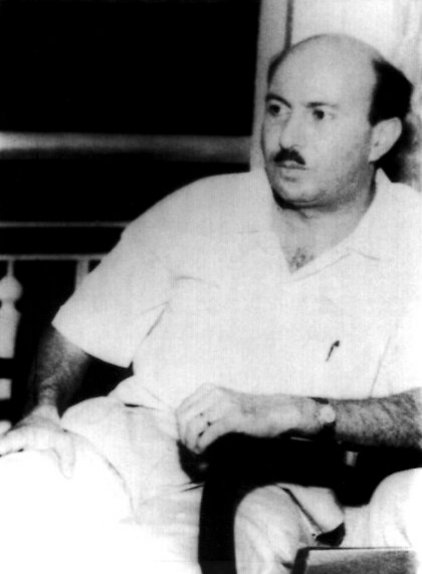

Wadi Haddad

In other words, Andropov was telling his leader that by making effective use of the agent “Nationalist,” the KGB would be able to execute its own operations, carried out by Haddad and his men, without leaving behind any fingerprints linking Soviet intelligence.

Haddad naturally had his own interests that led him to cooperate with the KGB. After the 1967 Six-Day War, he and Habash reached the conclusion that only terror attacks could truly hurt Israel and bring the Palestinian issue to the top of the world’s agenda. But to carry out such attacks, they needed weapons, funding, training and logistical support—all of which could be provided by the KGB.

In early July 1970, Brezhnev gave the KGB the green light to provide Haddad with money and RPG-7 launchers and missiles. But Haddad had much higher expectations. He told his KGB contacts that he expected “anti-aircraft surface-to-air missiles, landmines/roadside charges with remote detonation, naval mines, silencers, landmines/roadside charges with delayed fuses, and military training.”

The KGB noted that “Everything in Haddad’s list is available in Department V’s arms depots, except for the surface-to-air missiles,” but also that most of these weapons “were never provided to elements outside the borders of the Soviet Union.”

Despite this, Moscow decided to grant most of Haddad’s wishes—except for his request for anti-aircraft missiles—marking the beginning of “Operation Vostok.” Any markings that could lead back to the USSR were removed from the weapons, while some items were deliberately provided from a Western source: Guns from West Germany, American rifles, and British silencers.

The Model Snop remote-donation explosives had “a lifespan of a year and a half and remote detonation in urban areas of up to 2 km, and in open areas of 15-20 km.” The long-fused mines could be calibrated to detonate from anywhere between “15-144 minutes” after being planted.

At the time, Haddad was living in Beirut and contact with him was done through the KGB station at the Lebanese capital, usually in surreptitious meetings in one of his hiding places. Haddad sought to maintain complete secrecy—even from his boss George Habash. It worked relatively effectively, until the Israelis came into the picture.

Israeli intelligence located one of Haddad’s hiding places, an apartment on 8 Muhi A-Din al-Hayat Street in Beirut. On the night of July 10, 1970, Israeli naval commandos landed on the beach in Beirut in rubber boats to deliver two RPG launchers to the operatives of the Mossad’s elite assassination unit Caesarea. The Mossad operatives rented an apartment with a view of Haddad’s window, from where they fired two RPG missiles into the living room at 2pm the next day.

“There were two rooms in the apartment,” Mike Harari, the commander of the Caesarea Division, told me in his last interview before passing away.

“One was used as a living room, and the other was where the wife and daughter were,” Harari recounted. “Golda (Meir, Israel’s prime minister at the time) ordered us to ensure that not a hair on the head of any innocent person be harmed, otherwise I would have demolished the entire floor.

“The (Mossad) operative saw him (Haddad) in the living room and aimed the missile in that direction, set the timer, and left. A moment before (the missile was fired), the terrorist moved to the other room—and survived.”

‘Pathological hostility’

News of this assassination attempt in Beirut made it all the way to Brezhnev—a reflection of how important the incident appeared to the Russians—and increased Haddad’s value in the eyes of the KGB.

Soon afterwards, the KGB decided to use Haddad for a highly sensitive operation of its own: abducting the head of the CIA station in Beirut and taking him to Moscow for interrogation. “This will allow for obtaining credible information on American intelligence’s plans and operations in the Middle East,” Andropov wrote to Brezhnev.

The CIA station chief was described as “born in Denver, Colorado, 1918. Anti-Soviet, pathological hostility towards the USSR and communist ideology. Operates against Soviet institutions and diplomatic missions. Operated against Soviet citizens.”

Andropov promised Brezhnev that no one would suspect the KGB of being behind this abduction because “recently, Palestinian organizations have increased their guerrilla warfare against American targets, fighters and agents. The governments in Lebanon and America will suspect Palestinians carried out the abduction.”

On May 5, 1970, Brezhnev gave the green light and “Operation Vint” (screw) was underway.

The Mitrokhin documents include surveillance reports on the CIA chief: “He lives on the fourth floor of 168-174 Ramlet El Baida Boulevard. He owns a Mercury Comet, diplomatic license plate 104/115, light blue.” The reports also mention that he has a “dog, a black poodle, he walks it alone.”

The Operation Order details the abduction plan: “A rag will be pressed to his nose and mouth soaked with a chemical that will cause him to lose consciousness for three to five minutes. During that time, he will be injected with a sedative.” According to the KGB doctors who provided the sedative, “after a while he would regain consciousness, be able to sit and understand what’s happening, but would not be able to resist.”

After abducting the CIA station chief, the Operation Order continues, he would be taken to the Baalbek area, from where he was to be smuggled to Syria and kept at a secure KGB facility in the Zabadani area. There, he would undergo harsh interrogation, during which he would disclose information on American intelligence. “The idea is to get him to understand that he could not return to his country (because he disclosed information) and the only option he has left is to seek political asylum in one of the socialist nations.” If the CIA chief maintains his silence, the Operation Order wastes few words on what should be done: “In such a case, he must be killed.”

The abduction operation never got off the ground. The CIA station chief likely suspected he was being followed and therefore increased his security.

Other Americans were not as lucky: In August 1970, in a joint operation, Haddad and the KGB managed to abduct Prof. Hani Korda, an American academic who was suspected by the KGB (quite possibly wrongly) of having ties to the CIA. Prof. Korda was smuggled from Lebanon to a PFLP base in Jordan, where he was tortured but refused to admit to cooperating with American intelligence and was eventually released.

Two months later, Haddad’s men abducted Aredis Derounian, an Armenian-born American journalist. He too was suspected of cooperating with the CIA. According to the Mitrokhin documents, Haddad’s men found two passports and a significant amount of documents in Derounian’s apartment in Beirut. The documents were handed over to the KGB for examination while Derounian was incarcerated in a Tripoli refugee camp. There he was interrogated, but eventually managed to escape his captors and found shelter at the US Embassy in Beirut.

It was not just Haddad with whom the Americans had to contend. The KGB also recruited his fellow PFLP terrorist Abu Ahmed Yunis as a paid agent, giving him the codename “Tarshikh.”

In 1976, Yunis commanded an operation to assassinate the US ambassador to Beirut, Francis E. Meloy, Jr. The operation itself is not mentioned in the Mitrokhin documents, but it’s difficult to imagine it was carried out without the knowledge of the KGB. The assassination might have even been ordered by the Soviets.

Overall, the KGB was very pleased with Haddad and his men. “It appears worthwhile to actively use the ‘Nationalist’ (Haddad) and his men to carry out aggressive operations directly aimed at Israel,” a senior KGB official wrote to Andropov.

Shortly after that, Haddad and Yunis, in cooperation with the KGB, mounted an attack on the El Al offices at the Athens Airport on July 19, 1973. They also continued their multi-pronged assault on a number of separate occasions which included the bombing of Israeli institutions, the blowing up of an American oil pipeline and the hijacking of an American jet airliner, which they blew up after emptying it of its passengers.

‘Camel f***ers’

Through the KGB, Haddad also established close ties with the Stasi, East Germany’s intelligence service. Outwardly, the Germans were very polite in their treatment of Haddad and his cohorts; but internal Stasi correspondences illustrate the true racist sentiments which prevailed among the ranks about the Palestinians, who were dubbed “camel f***ers” by the Germans.

Even so, the Stasi provided training and weapons to the PFLP and, among other things, helped them prepare for “Operation Nasos” (pump), which was carefully planned by Haddad and the KGB over the course of several months.

This was the PFLP’s first naval operation—a daring plan that entailed shooting RPGs at an Israeli tanker that was secretly transporting oil from Iran to Israel through the Red Sea.

For the KGB, there was great value in such an operation: Hitting a significant Israeli target while at the same time exposing the secret oil ties between Israel and Iran, whose ruler, the Shah, was adopting a pro-Western approach at the time. All of this could be achieved without leaving any trace of Soviet involvement—a classic move of the “shadow war.”

The selected target was the Coral Sea oil tanker, which was sailing under a Liberia flag en route from Iran to Eilat. On June 11, 1971, two of Haddad’s top men sailed from the coast of southern Yemen towards the tanker in a speedboat. The Soviets gave the two the poetic codenames “Chuk” and “Gek,” named after two Soviet children who were cultural heroes to anyone who was raised in the USSR.

In the Strait of Bab el Mandeb they located the tanker just as the KGB planned. In an early morning hour, the terrorists approached the tanker and fired several missiles at it, with five hitting the tanker. When they saw the flames rising on deck, they concluded that their mission had been accomplished and quickly left the scene, heading back to Yemen where Haddad was awaiting their arrival.

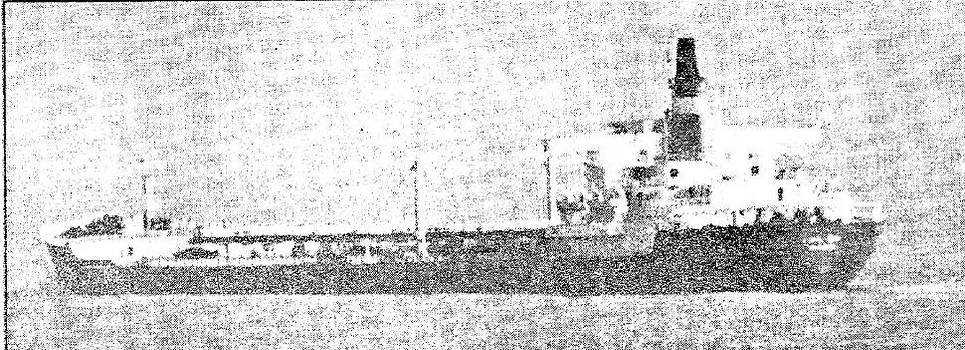

Coral Sea

Coral Sea

A statement released by the PFLP immediately after the attack read: “The missiles hit the tanker in two places … the oil caught fire and the tanker immediately came to a halt, following which it started to sink.”

But Haddad’s celebrations of the success of the operation were premature and short-lived. The tanker may have ignited, but thanks to a swift and daring action by its captain, Marcus Mouskus, the sailors managed to extinguish the fire, save the tanker—and likely save their own lives as well.

The action was one which earned Mouskus the Medal of Distinguished Service from the Israeli government, making him the first non-Israeli citizen (and the only one so far) to be the recipient of that honor.

Even though the tanker didn’t sink, Haddad greatly benefited from the international attention his daring attack at sea garnered, allowing him to demand more and more weapons for a series of attacks he planned for the coming years against Israel and other Western elements. Some of these attacks were carried out, while the rest were foiled by the Mossad, which had a source inside the PFLP at the time.

The KGB also helped one of Haddad’s top operatives, Taysir Quba’a (codenamed “Kim”), to contact members of radical left-wing organizations in western Europe—including the Red Brigades in Italy and the Baader-Meinhof Group in West Germany—so he could recruit them for joint operations. With the help of German terrorists, the PFLP attempted to down an El Al plane in Nairobi in January 1976 and successfully seized and diverted an Air France plane carrying Jewish and Israeli passengers to Entebbe in June of that year, among other attacks.

In return for the arms shipments he received from the KGB, Haddad agreed to carry out assassinations of “traitors to the motherland”—mostly defectors from the USSR—and even visited Moscow a few times to coordinate these operations.

During that time, in the second half of the 1970s, several delegations of Haddad’s men travelled to the Soviet Union to be trained by the KGB. They were trained in different areas of intelligence work, counterintelligence, interrogations, surveillance, sabotage techniques, firing guns and rifles, and more. There really isn’t a way to account for just how much blood spilling—mostly that of Israelis—this training contributed to.

The close cooperation between Haddad and Soviet intelligence services continued until early 1978, when he was poisoned in an attack attributed to the Israeli Mossad. When the doctors in Baghdad stood helpless by his bedside, Arafat asked the KGB to help him. The Soviet spy agency had Haddad hospitalized under a false name at a hospital in East Berlin, but despite the efforts of the best doctors brought in by the Stasi, Haddad died in intense agony on March 29, 1978.

Expanding ties in the PLO

The KGB may have lost its most important Palestinian agent, but by that time it had already managed to entrench its ties with the other Palestinian organizations. According to the Mitrokhin documents, the KGB provided support to Nayef Hawatmeh (codename “Inzhener,” meaning engineer), the leader of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), and used the DFLP’s newspaper, al-Hurriya, to spread KGB messages and propaganda.

Ahmed Jibril (codename “Mayorov”), the head of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC), also received support, both directly from Moscow and through the commander of Syria’s Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Gen. ‘Ali Duba, under whose wing Jibril operated. Jibril’s men aided the KGB, for example, in gathering intelligence in different Western nations and in Third World countries to which the Soviet spy agency had a difficult time gaining access.

Special ties were also forged between the KGB and the Western Sector—a Fatah unit under the command of Khalil al-Wazir (Abu Jihad), who was responsible for the 1975 Savoy Hotel attack and the 1978 Coastal Road massacre, among others. The Mitrokhin documents only reach 1986, but according to other sources, the KGB’s contact with Abu Jihad continued until he was assassinated by Israel in 1988.

In 1973, the KGB decided to change its attitude towards Yasser Arafat and his Fatah faction as the Palestinian organization’s standing in the international arena strengthened. The KGB’s operational and intelligence cooperation with the PLO was mainly conducted through Salah Khalaf (Abu Iyad), who was responsible for countless terror attacks against Israel.

Abu Iyad, whose codename was “Kochubey,” received a significant amount of weapons, intelligence, assistance and training for his men from the KGB. In return, the KGB directed some of Fatah’s operations and received “information about Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Algeria.” In other words, the Fatah spied on Arab nations for the KGB.

Abu Iyad was highly valued by the KGB, unlike some of his men. KGB specialists who were training Fatah men in Moscow met with quite a few difficulties and complained to their superiors that many of the cadets were characterized by “low standards, alcoholism and sexual offenses.”

Out of the 194 Fatah men who were sent to train in the USSR, 13 were expelled and sent back home. According to a senior official at the KGB’s academy, the number of expelled would’ve been closer to half of the cadets had they been required to meet the same standard as ordinary cadets.

Infiltrating the Mukataa

The two most important KGB recruitments from the PLO during the second half of the 1970s were of people who still play a major role in Palestinian politics today.

According to the Mitrokhin documents, the KGB had an agent at the heart of the PLO whose file describes him as “a member of the PLO’s executive committee and a member in the politburo of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP).” This was none other than Yasser Abed Rabbo, one of the top officials in the Palestinian Authority, who held a number of senior roles in the PA over the years, was a chief negotiator in talks with Israel, and one of the architects of the Geneva Initiative.

Abed Rabbo was fired by Mahmoud Abbas when the latter was elected, but stayed on as a senior advisor to the Palestinian president.

For the most part, the Mitrokhin documents don’t provide details about the information with which the agents provided the KGB, instead merely stating the fact that they were agents. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note the way Abed Rabbo is defined in the documents—as an “informant,” who is ranked below “agent” in the level of importance to the KGB. This means that Abed Rabbo’s contact with the KGB was done without the knowledge of the organization he belonged to.

The second and more important KGB recruitment was of the agent “Krotov” (mole), who was described in the KGB’s files as “born in 1935, Palestinian, prominent figure both politically and socially. Lives in Syria, a member of the PLO Central Council.”

As reported on Channel 1, based on research conducted by Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez, agent “Krotov” is none other than Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority.

The Mitrokhin documents, which have been corroborated by information gathered over the years by Israeli intelligence services, provide further details about agent “Krotov.”

The KGB began Abbas’s “first stage of recruitment” around 1979, when Abbas arrived in Moscow to study at the Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia. In describing those initial contacts, his KGB file notes that “it’s still unclear whether the object will agree to cooperate.”

The university’s declared goal was to aid elements in the Third World and in Africa in obtaining higher education—while increasing the influence of the USSR and of communism in the developing world. But the university had other roles, too. Among other things, the KGB—that essentially controlled the campus—recruited agents there.

Abbas had already been a graduate of the Damascus University’s Faculty of Law, and was accepted in Moscow to study for a Candidate of Sciences degree, which is the Russian equivalent of a PhD in Social Sciences at Western universities.

The university’s president at the time was Yevgeny Primakov, who had close ties to the KGB. He later went on to become the head of the KGB First Chief Directorate and helped it on its transition to the control of the Russian Federation government, under the new name Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). He then served as Russia’s minister of foreign affairs and later still as its prime minister.

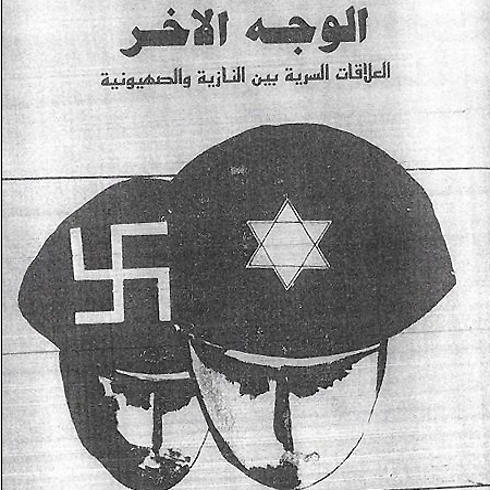

As university president, Primakov appointed his top Middle East expert, Prof. Vladimir Ivanovich Kiselev, as the Palestinian leader’s dissertation adviser. Abbas’s CandSc thesis “The Other Side: The Secret Relationship Between Nazism and Zionism”—a lampoon of blatant lies, including Holocaust denial and accusations that Zionists “assisted” Hitler—was completed in May 1982 and released as a book two years later.

By that time, Abbas had already returned to Lebanon and used the PLO archive to spread Soviet propaganda prepared by the KGB and the Stasi, which accused “Western Imperialism and Zionism” of cooperating with the Nazis. This was done as part of a widespread propaganda campaign run by the KGB at the time, which attempted to create a link between anti-Soviet elements and the Nazis—the ultimate symbol of evil.

This propaganda material was later seized in an Israeli Military Intelligence raid of the PLO archive in Beirut, and it constitutes, at the very least, additional circumstantial evidence attesting to the links between Fatah and Abbas and the Soviet intelligence services.

As ties between Abbas and the Russians grew closer, an internal KGB report concisely noted that developing progress: “Krotov is an agent of the KGB.” According to the KGB’s definition, those who reach the level of “agent” are those who “consistently, systematically and covertly carry out intelligence assignments, while maintaining secret contact with an official in the agency.” In other words, according to the KGB documents, Abbas was authorized to be a KGB spy within the PLO.

Yedioth Ahronoth was unable to obtain a response from Mahmoud Abbas’s office or from Yasser Abed Rabbo by the time of publication.

However, a former senior Fatah official who asked to remain anonymous told us that Abbas was not an agent of the KGB in the sense that he acted against Fatah’s interests but rather was “a Fatah-authorized contact appointed by Arafat to coordinate the transfer of measures and arms from the Soviet Union to the Palestinians”—contacts that the official doesn’t deny. The official added that the “Soviet Union and its intelligence services greatly and significantly aided the Palestinian struggle for independence.”

Research and translation from Russian by Will Styles, Alexander Tabachnik, Yana Sofovich and Yael Sass.

The writer would like to extend his gratitude and appreciation to Prof. Christopher Andrew and Dr. Peter Martland of Cambridge University.

(First published on Nov 14, 2016)

Is this article copyright ?

There has been the war that everyone sees and then the war underneath it all. So diabolical.