On September 9, 2016, U.S. Congressman Jeff Fortenberry (R-Nebraska) introduced a bipartisan resolution in the U.S. House of Representatives calling for support for the creation of a Nineveh Plain province in Iraq. A press release on the measure noted that “the Nineveh Plain was once a thriving, pluralistic area of Iraq with a rich tapestry of religious and ethnic diversity. This resolution, which follows on the Government of Iraq’s own initiative to create a province in the Nineveh Plain region, seeks to restore the ancestral homeland of so many suffering communities.”

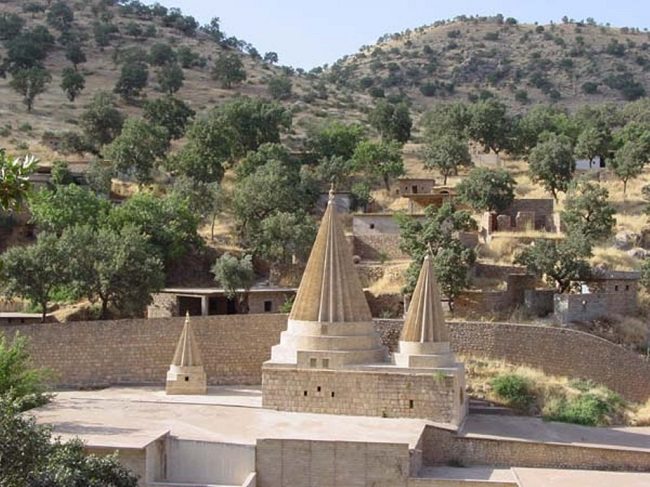

The actual borders of such a possible region are not entirely clear, but can be said as constituting all or most of the administrative districts of Hamdaniya, Tel Kayf, and Sheekhan. This area was, at least until the ISIS invasion of June-August 2014, particularly diverse, with significant populations of Assyro-Chaldean Christians, Yazidis, and Shabak.[1] The Christian population was clustered in some very ancient towns and villages, such as Alqosh, Bartella, and Bakhdida, particularly important in the survival of the autochthonous Syriac-speaking Christian communities for the past two thousand years. Most of these populations were dispersed as of August 2014 and remain either as internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Kurdistan or as refugees elsewhere.

This is the area where the Islamic State (ISIS) blew up large parts of the historic fourth-century Mar Behnam Syrian Catholic monastery, described by Jules Leroy in 1963 as “unique” as a result of its redecoration in the 12th century and “the most representative monument of Christian art in Mesopotamia at the time of Atabeks of Mosul.” Nearby Yazidi and Shia shrines were destroyed at the same time.[2] Individuals were murdered or enslaved by the Islamic State, sometimes with the connivance of some Sunni Arab Muslim neighbors. Almost as tragic was the displacement of local people from their ancestral homes with only the clothes on their backs.[3]

The Congressional bill follows in the steps of a long series of statements from Iraqi officials on the subject. Generally, the concept has been at least given lip service by a wide range of Iraqi Shia and Kurdish politicians. In January 2014, the Iraqi Council of Ministers approved, in principle, turning the districts of Tuz Khurmato, Fallujah, and the Nineveh Plain into provinces. Ironically, it was the Sunni Arab leadership in Mosul – the same population that the Islamic State has sought to make its own – that opposed the division of Nineveh Governorate.[4] Not surprisingly, now that the possible liberation of Mosul nears, some Sunni Arabs talk of making the area an autonomous region, while the Iraqi Kurdish leadership has proposed separating the Yazidi (Sinjar) and Nineveh Plain districts from Mosul, making Nineveh Governorate into three separate entities.

The Christian and humanist in me wants this project to succeed, and believes that it should be tangibly supported by people of good will everywhere.[5] The former U.S. diplomat in me is much more cynical and fears that such a fragile concept could well be crushed between the contending, vaulting ambitions of Shia-ruled Baghdad and Kurdish nationalism, not to mention the need to appease an alienated and volatile Sunni Arab population based in Mosul.[6]

Three smart, dedicated American activists, with deep knowledge of the issue and the human terrain, recently outlined a thoughtful, nuanced plan that seeks to minimize many of the biggest pitfalls.[7] Especially important is their prioritizing the challenges of security and of community reconciliation.

The Nineveh Plain project has, at least, some real support within the Iraqi ruling class and is not something that can be categorized as a foreign imposition on local people. One unspoken challenge is how economically viable can this project be as we see donor fatigue and a shortfall in humanitarian assistance as the international community seeks to respond to constant, deep crises across the region.[8] Indeed, the entire country is threatened by a deep economic crisis exacerbated by rampant corruption and low oil prices.[9]

But beyond helping in the survival of battered historic communities, this project raises some important questions – not so much about Middle East Christians and Yazidis or even about Iraq but about the region as a whole. For years, the motivating ideologies of authoritarians in or out of power in the region have been strands of pan-Arabism or Islamism. Both have been used to impose tyranny, stamp out difference and diversity, and crush any move towards a more tolerant and diverse society (which actually existed in the region during the pre-modern era.) If pan-Arabism had a place for Arab Christians, it excluded Kurds and other non-Arabs. Islamism, of course, excluded or sought to subjugate Christians, Druze, Alawites and secularists and free thinkers of almost every stripe.

Both Arabism and Islamism still exert a powerful hold, officially and in the popular imagination. At times, they can even be combined.[10] The existence of the State of Israel is, of course, a constant, vivid challenge to both these worldviews. At different times over the past decades, Lebanese Christians, Assyrian Christians, Kurds, Amazigh and South Sudanese have also been marked as transgressors from this seemingly ceaseless, brutal drive towards unity, whether Arab or Islamist. And while the pan-Arabism parroted by sclerotic regimes seems to have withered on the vine, various contending forms of Islamism are still THE default political alternative in much of the region.

But much of the Middle East is in freefall today, with practically all pillars of authority and power shaken, and with the prospects of this great unraveling region wide continuing over decades to come. One has to wonder whether the moment for a more decentralized Middle East, one that can recognize local differences, local rights and greater autonomy, can finally be nearing.

Certainly the consequences of totalitarian centralizing authority, political, economic, cultural or even agricultural, are there for all to see in the Syrian nightmare of Bashar Al-Assad.[11] It may be that the latest U.S.-Russia-Syria-Iran agreement may “save” Syria, or that Syrian rebels may be able to outnumber and outlast Assad, but a more likely scenario may be a continuation of the status quo. If so, the eventual possibility of some sort of loose, de facto partition under the guise of federalism may become an option. The Syrian opposition still seems to be particularly opposed to such an outcome.[12] And at the same time, Assad talks of reconquering the entire the country.[13] In sync with the way the regional political game has been played, they both still want it all.

Beyond the countries of the Fertile Crescent, one can see value in more decentralized and autonomous arrangements, from North Africa to Sudan to Yemen. Such concepts are still mostly political heresy, but perhaps the time for heresy has come, but only if there is real local political will. It can’t be a Western project.

An Iraqi autonomous region or governorate of minorities may be a strange place to start a regional trend. But instead of building new empires perhaps the region may be much better served to think small and local. Instead of investing in more dreams of grandeur, perhaps investing in humility and in simple humanity could pay off this time.

As Robert Nicholson has suggested, it may be time for a new vision of a wounded region that is more organic, “smaller,” and prudent.[14] Building arrangements where oppressed groups are empowered and given autonomy, without prejudicing the rights of others, is not an idea which has been tried and failed.[15] It has hardly been tried at all in the Middle East where minorities are abused and marginalized, and so are majorities.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

Endnotes:

[1] Minorityrights.org/minorities/shabak, October 2014.

[2] Gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2015/05/12/what-weve-lost-mar-behnam-monastery, May 12, 2015.

[3] Ibtimes.co.uk February 6, 2015.

[4] Ishtartv.com/en/viewarticle,35343.html, August 23, 2011.

[5] Fides.org, “ASIA/IRAQ – Chaldean Patriarch: Christians used as a ‘token of exchange’ in political games on the Nineveh Plain, September 6, 2016.

[6] Nationalinterest.org, July 20, 2016.

[7] The-american-interest.com, September 9, 2016.

[8] Nst.com.my/news, August 29, 2016.

[9] Al-monitor.com, February 9, 2016.

[10] Aljazeera.com, February 4, 2008.

[11] Foreignpolicy.com, September 5, 2016.

[12] Reuters.com, March 10, 2016.

[13] Smh.com.au, September 13, 2016.

[14] Providencemag.com, December 4, 2015.

[15] Lawfareblog.com/why-minority-safe-haven-iraq-wont-work , July 24, 2016.