The appointment of one of the IRGC’s youngest generals can be seen as a sign of the Guards’ growing primacy in future Iranian military thinking, and perhaps an urgent push toward improving interoperability between often-competing armed services.

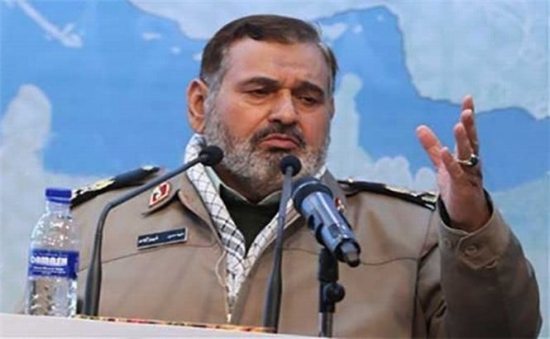

On June 28, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei appointed Maj. Gen. Mohammad Hossein Bagheri as the new chairman of the Armed Forces General Staff (AFGS), the country’s top military body. Bagheri is replacing Hassan Firouzabadi, who held the post for twenty-seven years and will now serve as yet another military advisor to Khamenei. Given Gen. Bagheri’s shadowy character, only time will tell what changes his appointment will bring to Iranian military doctrine and strategic culture, but his background provides several clues.

BAGHERI, FIROUZABADI, AND THE AFGS

Bagheri participated in the seizure of the U.S. embassy in 1979 when he was a freshman engineering student, but he soon changed course and joined the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). There he participated in campaigns against Kurdish insurgents and later Iraq. Very little is known about his role in the Iran-Iraq War; he is certainly not as famous as his older brother Hassan, who founded the IRGC’s military intelligence branch in 1980 and commanded a division when he was only twenty-seven. Yet the younger Bagheri is also a veteran of IRGC military intelligence as well as an IRGC strategist.

After Hassan’s uneven career of brilliant successes and costly defeats ended with his death in January 1983, his younger brother was named head of IRGC Ground Forces intelligence. And when the AFGS was formed in June 1988, right before the end of the Iran-Iraq War, he was brought aboard as acting deputy chairman for intelligence, a post he later assumed for many years until he was appointed director of staff and interoperability affairs.

The AFGS was established to oversee the merger of the national and revolutionary armed forces, as well as to supervise military, training, and organizational planning, to support the military industrial complex, to write defense budgets, to provide the commander-in-chief with timely intelligence, and to coordinate the affairs of the IRGC and the national army (aka Artesh). Although then-IRGC commander Mohsen Rezai was promised the top military job, he was never permitted to take it, mainly due to stiff Artesh opposition but also because the war ended before he could launch another “final” offensive. As acting commander-in-chief, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani had chosen to end the war peacefully and have then-prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi serve as AFGS chairman. Mousavi then brought aboard his ministers and deputies, including military advisor Firouzabadi and future president Hassan Rouhani.

Firouzabadi was seen as an outsider because he did not hail from either the Artesh or the IRGC. But as a rising star on the general staff, he received the new military rank of “Basiji Major General” from Khamenei in September 1989 and replaced the outgoing Mousavi as chairman. During his long tenure, Firouzabadi was credited with husbanding the IRGC from a war-ravaged organization to a hybrid conventional-asymmetric military force overshadowing the still-lagging Artesh. He also oversaw a growing military industry that produced a wide range of products amid international sanctions, from ammunition to space rockets.

While little is known about Firouzabadi’s actual strategic military thinking, his latest book focuses on “ethical security,” arguing that the dwindling of ethical values among Iranians is a threat to the future of the revolution. His successor, Bagheri, shares this view, though he is considered more knowledgeable and experienced in military affairs. Unlike most other IRGC commanders, who are quite outspoken about Iran’s domestic and foreign affairs, Bagheri remained in the shadows for most of his career and has rarely been seen in public except during military exercises.

At fifty-six, Bagheri is the youngest Iranian major general, but he is well-decorated for various classified achievements. He also holds a doctorate in political geography and reportedly teaches at Iran’s Supreme National Defense University. Like his predecessor, Bagheri can be regarded as an “outsider” because he does not belong to any known IRGC factions; in fact, this may be why Khamenei chose him over more senior (and arguably more popular) IRGC brass such as Gholam Ali Rashid or Yahya Rahim Safavi, the Supreme Leader’s top military advisor. Notably, Rezai’s recent return to military duty could be seen as a presumed bid for the AFGS chairmanship — hence his absence from Bagheri’s inauguration ceremony after being passed over yet again.

A POSSIBLE FUTURE?

Two factors stand out as the most likely reasons for replacing Firouzabadi: his health issues and Khamenei’s dissatisfaction with the general course of the Iranian armed forces. In his decree announcing the change, Khamenei wrote to Bagheri: “You are expected to oversee an upgrade to [Iran’s] military and security capabilities and the readiness of its armed forces and the popular Basij, and to improve their ability to respond in a timely fashion to any threat against the Islamic Republic at any level, using revolutionary determination.”

The last phrase is a clear code for the IRGC’s continuing primacy in Iranian military thinking. In the past, Bagheri has harbored negative sentiments against the Artesh, which might further affect the general staff’s future direction. Although Khamenei also appointed Bagheri’s vice chairman from the ranks of the Artesh — Gen. Abdolrahim Mousavi replaced IRGC general Rashid — this was more of a balancing act by the Supreme Leader and is unlikely to change his overall pro-IRGC calculus. Earlier today, Rashid was appointed head of the Khatam al-Anbia Central Staff, which is in charge of planning and coordinating operations across the entire armed forces. Khamenei also named a veteran IRGC pilot, Lt. Gen. Ali Abdollahi, as AFGS deputy for coordinating affairs, replacing a decorated Artesh veteran, Maj. Gen. Hossein Hassani Saudi, who will probably retire. Abdollahi has extensive security experience, previously working as the Interior Minister’s security deputy and acting commander of the police.

Indeed, the armed forces are as divided as ever — with the apparent exception of the air defense command, there is very little interoperability, and few joint or even coordinated exercises have been conducted in recent years. Therefore, Khamenei’s choice could be interpreted as a push for a more revolutionary course that weakens the national armed services even further. This approach would likely include devoting more money to new ways of fighting perceived and real enemies, and to continued foreign adventures in the region.

During his three decades atop the AFGS, Firouzabadi was able to maintain working relations with different governments representing different parts of the Iranian power spectrum, but it is yet to be seen if Bagheri will be able to demonstrate similar qualities in adapting to the country’s shifting politics. Regarding foreign diplomacy, he is expected to follow the tradition of other Iranian military commanders who have been quite outspoken in attacking the West and Israel. In his first press release as AFGS chairman, he called for the “liberation” of all Muslim lands.

Bagheri’s background also indicates which military strategies and tactics Iran might emphasize going forward. He enjoys close relations with the IRGC’s Qods Force, the elite branch responsible for extraterritorial operations, and he reportedly planned and helped execute missions deep inside Iraq in the 1990s, targeting Iranian Kurdish groups based there. He also helped expand the use of drones and intrusive intelligence collection. In keeping with these tendencies, Iran may expand its use of preventive and punitive surgical strikes; Bagheri is expected to put more strategic emphasis on tailored special operations and the intelligence collection aspects of the Qods Force and other special branches. His appointment could therefore mean more military operations in northern Iraq and perhaps even in Pakistan’s portion of Baluchistan, targeting Iranian Kurdish and Baluchi insurgent hideouts and training camps. In addition, the armed forces are expected to become leaner under his watch, fielding more long-range armed drones instead of more expensive and complex systems.

More broadly, Bagheri is said to be one of the IRGC’s strategic masterminds and is a strong believer in robust deterrence against perceived foreign threats, especially IRGC missile and naval deterrence. He is thought to be the theoretician behind the “threat for threat” concept, the IRGC’s recent notion of escalating its military posture step by step in proportion to the threat level the Islamic Republic faces. Bagheri also once supported an active military presence on the high seas, even as far away as the South Pole. In addition, he favors China over Russia, so his rise to the top military job might augur expanded military relations with Beijing.

CONCLUSION

Although it was perhaps time for a change in the AFGS leadership given Firouzabadi’s poor health and long tenure, the appointment of one of the IRGC’s youngest generals to replace him could also signal the Guards’ growing primacy in future Iranian military thinking. And since deficient interoperability remains a major problem, Bagheri’s appointment can be seen as an attempt to finally begin consolidating the national and revolutionary armed forces, as well as to improve interoperability until that time arrives.

Farzin Nadimi is a Washington-based analyst specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Persian Gulf region.