Analysts have wondered why Syria’s Druze have not joined the uprising against the regime of President Bashar Assad, despite the fact that the Druze were the first to rebel against the Egyptians in 1835 and against the French in 1925.

The truth is that the Baath regime since 1970 has systematically marginalized potential Druze leaders in Syria. Any Syrian Druze with leadership qualities was sidelined. The patron-client relationship established by the Baath demanded Druze allegiance to non-Druze Baath officials in order for the community to receive its share of resources from the state.

The last true Druze leader in Syria was Mansour al-Atrash, the son of Sultan al-Atrash, one of the great leaders of the 1925 Syrian revolt against the French. Mansour paid a price for his opposition to the Assad regime, retreating from public affairs during the 1970s. Eventually, the Druze became leaderless and the community retreated to satisfying its day-to-day concerns.

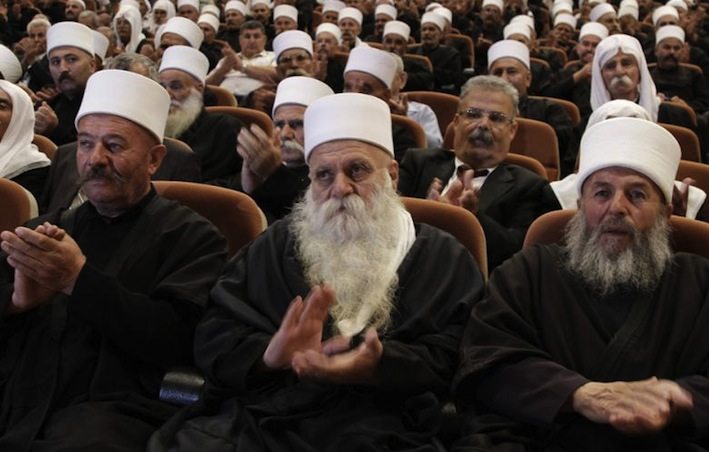

In communities where political leaders are absent from public affairs, religious institutions tend to fill the gap. In the case of the Druze, the institution represented by the three sheikhs al-Aql played this role. The Assad regime understood the role and the influence of the sheikhs al-Aql among the Druze, and hence completed its domination over the Druze by intervening in appointing the leaders of this institution.

Therefore, when the uprising started in 2011, the absence of a political leader allowed the regime to mobilize its agents in the Mashyakhat al-Aql to prevent possible Druze support for the rebels in Deraa. However, a few Druze joined the rebellion nonetheless, among them Lt. Khaldoun Zeineddin, who was killed in action in early 2013.

Among the religious men, one of the three sheikhs al-Aql, Sheikh Ahmad al-Hajari, who descends from the distinguished Druze religious leader Ibrahim al-Hajari, showed dissatisfaction with the Assad regime’s behavior against citizens. Sheikh Ahmad expressed sympathy with the rebels’ cause and there were rumors that he was planning to endorse the rebellion against Assad. He visited Druze towns located close to Sunni towns in Deraa, and he was quoted as saying that the Druze could not live in isolation from the events, and could not oppose the will of the majority of the population.

He also opposed attempts by the Lebanese Druze politician Wi’am Wahhab to establish a Druze militia loyal to Assad and sponsored by Syrian military intelligence.

This was too much for the regime, so as a first step it withdrew the care and the protection it provided to religious officials. When this did not stop Sheikh Ahmad, he died mysteriously in the aftermath of a car crash in March 2012. The car he was travelling in collided with another car in southern Syria. In most situations like this, a lawyer will have been contacted at the soonest possible moment in pursuit of maximum compensation. However, this situation was different. According to eyewitnesses, Sheikh Ahmad was not in critical condition when he was placed in an ambulance, but was declared dead before reaching the hospital. This raised questions about the role of the regime in his death. More often than not, road traffic accidents like this also involve trucks and so people would want to see a truck accident attorney Turlock has offering to step in, but sadly they can’t operate in this area of the world.

It appears the regime has shifted its strategy from marginalizing independent Druze leaders to liquidating them.

Sheikh Hekmat al-Hajari became Sheikh al-Aql after Sheikh Ahmad’s death, and along with the other two sheikhs al-Aql, Hammoud al-Hannawi and Youssef Jarbou, he supported the regime. But the rhetoric of the three sheikhs al-Aql did not hinder the rise of a new Druze opposition among the religious men, mainly due to regime corruption in distributing primary needs to the population, and the death of a number of Druze political prisoners in regime detention centers.

Thus, a young religious man with no official post, Sheikh Abou Fahd Wahid Balous, rose to prominence. He openly denounced the regime, insulted Assad for “selling the country to the Iranians,” and started to mobilize Druze youngsters by reminding them of their past glory.

Sheikh Balous was also active in practical terms, for in 2015 he led a group of young armed religious men in a march against a regime-controlled checkpoint in Swaida, before disarming the soldiers there and demolishing the checkpoint. Following this episode, he called upon the regime to dismiss the head of military intelligence in Swaida, Colonel Wafik Naser, who nevertheless is in place.

The Sheikh Balous phenomenon is a reaction to the submission of the highest officials in the Druze community to the Syrian regime. Sheikh Balous’ actions are particularly important because they reinstate an element of self-esteem among the Druze without the need to depend on the regime for protection.

Following the actions of Sheikh Balous, Sheikh Hannawi, one of the three sheikhs al-Aql, demanded that the Druze of Swaida be equipped militarily as they could no longer depend on the Syrian army for protection. He also called on the Druze to take their decisions independently from the security establishment.

Similar uncertainty exists in Idlib, where a few thousand Druze live on the fault line between the Nusra Front and regime troops. Until now, the Druze of Idlib have shown signs of cooperating with Nusra and the opposition, while keeping limited lines of communication open to the regime.

While there are reports that ISIS plans to attack the Swaida region, this remains unclear, especially as the group may be focused on defending Ramadi. Moreover, it will not be easy to send reinforcements from Palmyra or eastern Syria to Swaida as ISIS is not well-established in southern Syria. In addition, the Nusra Front will not accept to share power there with ISIS.

As for the Assad regime, it will definitely prefer a slaughter of the Druze by ISIS in Swaida to distributing weapons to them for protection. A massacre would help the regime to continue to make the argument that it alone protects minorities.

What does this mean for Druze elsewhere in the Middle East? Taymour Jumblatt, who is in the process of taking over from his father, the Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, will have to deal with the dilemma of the Syrian Druze sooner or later. More likely the Lebanese Druze will provide logistical and political support to their brothers in Syria, so they can maintain an acceptable position in the post-Assad era. Cooperation and communication with Sheikh Balous is a good place to start.

Eduardo Wassim Aboultaif is a doctoral candidate at the University of Otago in New Zealand who studies deeply divided societies. He wrote this commentary for THE DAILY STAR.