CAIRO — After I gave a reading in Britain last year, a woman stood in line as I signed books. When it was her turn, the woman, who said she was from a British Muslim family of Arab origin, knelt down to speak so that we were at eye level.

“I, too, am fed up with waiting to have sex,” she said, referring to the experience I had related in the reading. “I’m 32 and there’s no one I want to marry. How do I get over the fear that God will hate me if I have sex before marriage?”

I hear this a lot. My email inbox is jammed with messages from women who, like me, are of Middle Eastern and Muslim descent. They write to vent about how to “get rid of this burden of virginity,” or to ask about hymen reconstruction surgery if they’re planning to marry someone who doesn’t know their sexual history, or just to share their thoughts about sex.

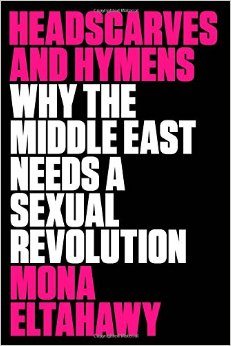

Countless articles have been written on the sexual frustration of men in the Middle East — from the jihadi supposedly drawn to armed militancy by the promise of virgins in the afterlife to ordinary Arab men unable to afford marriage. Far fewer stories have given voice to the sexual frustration of women in the region or to an honest account of women’s sexual experiences, either within or outside marriage.

I am not a cleric, and I am not here to argue over what religion says about sex. I am an Egyptian, Muslim woman who waited until she was 29 to have sex and has been making up for lost time. My upbringing and faith taught me that I should abstain until I married. I obeyed this until I could not find anyone I wanted to marry and grew impatient. I have come to regret that it took my younger self so long to rebel and experience something that gives me so much pleasure.

We barely acknowledge the sexual straitjacket we force upon women. When it comes to women, especially Muslim women in the Middle East, the story seems to begin and end with the debate about the veil. Always the veil. As if we don’t exist unless it’s to express a position on the veil.

So where are the stories on women’s sexual frustrations and experiences? I spent much of last year on a book tour that took me to 12 countries. Everywhere I went — from Europe and North America to India, Nigeria and Pakistan — women, including Muslim women, readily shared with me their stories of guilt, shame, denial and desire. They shared because I shared.

SHARE YOUR STORIES

Talking About Taboos

“Where are the stories on women’s sexual frustrations and experiences?” Mona Eltahawy asks about women of Middle Eastern and Muslim descent. Tell us about the taboos you have learned to live with, or let go of, in the comments. We may highlight your response in a follow-up to this piece.

Many cultures and religions prescribe the abstinence that was indoctrinated in me. When I was teaching at the University of Oklahoma in 2010, one of my students told the class that she had signed a purity pledge with her father, vowing to wait until she married before she had sex. It was a useful reminder that a cult of virginity is specific neither to Egypt, my birthplace, nor to Islam, my religion. Remembering my struggles with abstinence and being alone with that, I determined to talk honestly about the sexual frustration of my 20s, how I overcame the initial guilt of disobedience, and how I made my way through that guilt to a positive attitude toward sex.

It has not been easy for my parents to hear their daughter talk so frankly about sex, but it has opened up a world of other women’s experiences. In many non-Western countries, speaking about such things is scorned as “white” or “Western” behavior. But when sex is surrounded by silence and taboo, it is the most vulnerable who are hurt, especially girls and sexual minorities.

In New York, a Christian Egyptian-American woman told me how hard it was for her to come out to her family. In Washington, a young Egyptian woman told the audience that her family didn’t know she was a lesbian. In Jaipur, a young Indian talked about the challenge of being gender nonconforming; and in Lahore, I met a young woman who shared what it was like to be queer in Pakistan.

My notebooks are full of stories like these. I tell friends I could write the manual on how to lose your virginity.

Many of the women who share them with me, I realize, enjoy some privilege, be it education or an independent income. It is striking that such privilege does not always translate into sexual freedom, nor protect women if they transgress cultural norms.

But the issue of sex affects all women, not just those with money or a college degree. Sometimes, I hear the argument that women in the Middle East have enough to worry about simply struggling with literacy and employment. To which my response is: So because someone is poor or can’t read, she shouldn’t have consent and agency, the right to enjoy sex and her own body?

The answer to that question is already out there, in places like the blog Adventures From the Bedroom of African Women, founded by the Ghana-based writer Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, and the Mumbai-based Agents of Ishq, a digital project on sex education and sexual life. These initiatives prove that sex-positive attitudes are not the province only of so-called white feminism. As the writer Mitali Saran put it, in an anthology of Indian women’s writing: “I am not ashamed of being a sexual being.”

My revolution has been to develop from a 29-year-old virgin to the 49-year-old woman who now declares, on any platform I get: It is I who own my body. Not the state, the mosque, the street or my family. And it is my right to have sex whenever, and with whomever, I choose.

The author is very correct.its she who is to give account to the Almighty God of Abraham,Isaac and Israel at the end of the life here on Earth. The most important is the relationship with God through Jesus Christ. All human just must accept Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior to be reconciled to the creator of Heaven and Earth. Your salvation matters a lot in Heaven. God bless you as you read this little piece of advice and comply in Jesus Name. Amen.