Three decades later, none of the parties have kept that pledge. Hezbollah has undermined the state Husseini envisioned by carving out its own state-within-a-state, while virtually every other major party systematically diverted state resources into their own war chests. All that remains is an empty husk of a government tens of billions of dollars in debt.

Lebanon and the Levant region around it have fallen into a catastrophe that Husseini foresaw but ultimately could not prevent. When he inherited leadership of the Amal movement from his co-founder Musa Sadr after the latter’s murder in 1978, Husseini recoiled from deploying Amal as a militia in Lebanon’s raging civil war. He resigned Amal’s presidency in 1980 rather than become a warlord himself, something his successor at Amal’s helm, Nabih Berri, was only too willing to do under Hafez al-Assad’s direction. Later, when Hafez al-Assad pushed the Lebanese in 1992 to curtail Husseini’s speakership of the Lebanese parliament and replace him, again with Nabih Berri, the reason was that Husseini opposed the joint Assad-Saudi-approved plan to expropriate large tracts of Beirut property to Rafiq Hariri for post-war development.

Husseini particularly opposed the plan for Lebanon to finance the reconstruction through vast public debt that would be overseen by the man Hariri brought to the Central Bank, Riad Salameh. Yet having pushed Husseini out of leadership for Hariri’s sake, the Syrian regime would kill Hariri a dozen years later, and thirty-two years later Salameh faces near-universal blame for overseeing the death of the country’s economy through the debt scheme Husseini resisted.

Though he was born to a prominent Shia family in the Bekaa, Husseini was an opponent of Shia militancy throughout the decades of Hezbollah’s rise to power and Qassem Soleimani’s quest to turn Lebanon into a satrapy of Tehran. For Hezbollah and Tehran, he was a problematic critic, given his impeccable Shia credentials as a sayyid from the family of the Imam Hussein. For years, the Iranian regime and Hezbollah tried unsuccessfully to coax or intimidate Husseini into their orbit.

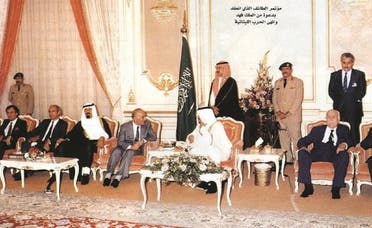

Tensions between Husseini and Tehran’s proxies in Lebanon culminated in his high-profile rejection of the 2008 Doha Accord that delivered Hezbollah the lion’s share of power within the country’s parliamentary system and effectively overturned the Taif Agreement. As the parliament met to review the Doha deal on August 12, 2008, Husseini stunned the country by delivering a speech resigning his parliamentary seat. Some excerpts from his speech are worth remembering.

The Taif Agreement, Husseini observed, had, above all, called upon the country’s parties to establish a constitutional state. “We have a country,” he said, “and maintaining our homeland in an ocean of events is by no means a small feat,” but the Lebanese had failed thus far to establish a state. “It is as if we have not learned from past experience, as if we wanted a state without institutions, as if we wanted a homeland without citizens,” he noted. “The ruling class is capable of something if it has a desire for it, but the reality is that it has so far lacked such a desire” and in the face of such a reality, Husseini had no wish to continue in office and lend credibility to a system he no longer had faith in. “To me, Lebanon is a homeland, and the Lebanese are citizens,” he said, “[but]a man may become an obstacle to what he wants most and must know his limits.” With those words, Husseini went into political exile.

It would have been simple for Hussein el-Husseini to amass enormous power and wealth, had he wished to, by simply joining forces with the “Axis of Resistance” as so many others in the Levant have done. He could have chosen to become a warlord, maintaining his own private army, as others have done. He could have accepted any of many offers to become a government minister and then used the post to drain the state’s coffers and become a billionaire, as other Lebanese ministers have done and are still doing.

There is no reason he could not have been parliament speaker up to the day of his death, had he been willing to cooperate with Assad and Iran’s consolidation of power in Beirut. And as a Shia grandee, it would have been simple for him to collude in breaking Lebanon into sectarian communities and then rule over the Shia fragments, as the leaders of Lebanon’s political class–and Bashar al-Assad next door, for that matter–have tried to do via their own communities.

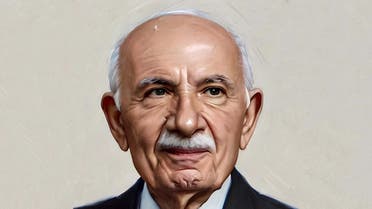

Hussein el-Husseini did none of that. He was a genteel, nonviolent man in an era of warlords, a state-builder in an era of state capture and fragmentation, and a civilian in an era of militants. In a time of corruption, he spent his last years founding an anti-corruption NGO and promoting Lebanon’s protest movement. He spent his career in pursuit of the idea that Lebanon’s many fragmented sects, ethnicities, and parties could not just co-exist in one country, but also combine to establish a sovereign nation state. At his passing, he leaves behind a country and a region ruinously departing from his vision in almost every way. A Levant region wrecked by Khamenei, Soleimani, Assad, Nasrallah, Mughniyah, and their minions needs the next Hussein el-Husseini to step forward.