There used to be a public health phenomena called Sick Building Syndrome (SBS).

The idea was that dirty ducts and air vents inside modern buildings were making people sick. In the early 1990s, SBS was linked to lung cancer, asthma and a number of respiratory diseases. Medical conferences were held. Academic journal articles were published. Media stories were written about this potentially dangerous problem.

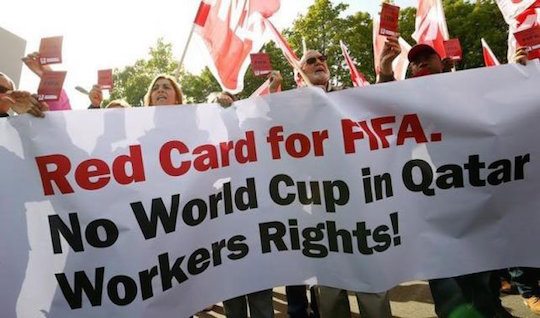

Workers in Qatar

Then the non-smokers rights advocates pointed out that much of the research about SBS was financed by the tobacco industry. In other words, a relatively minor issue was being promoted by the cigarette people to confuse the debate around the major health effects of smoking. Presumably, if some people thought their buildings were making them sick, they would go on smoking.

This all took place during the era that the powerful US news show 60 Minutes helped the tobacco industry downplay the links between nicotine and addiction. My former colleague Lowell Bergman, a producer at 60 Minutes, showed in a Hollywood film – The Insider, staring Al Pacino and Russell Crowe – how 60 Minutes had caved into the commercial pressures of the tobacco industry and edited his story on their behalf.

There is a faint whiff of this sordid episode on the news that 60 Minutes Sport is running a documentary on human trafficking linked to sports. One of their principal aides in the story is the Qatari-financed International Centre for Sports Security (ICSS).

For those readers who have missed previous blogs, the ICSS is an organization that I, and many others, regard as a joke. Launched in Doha a few months after the controversial decision to award the 2022 World Cup to Qatar, it is mostly funded by Qataris close to the ruling elite. The ICSS claims to be concerned with the integrity and ethics in sport. However, to this date, they have not mounted any credible investigation into the activities of the very prominent Qatari football executive Mohammed bin Hammam who has been linked to corruption and bribery in the acquisition of the 2022 World Cup by Qatar.

So it was great interest to see the ICSS promoting the issue of human trafficking linked to sport.

I thought, “Finally the ICSS are investigating a modern scandal of labour exploitation and potential blood money in international sports! They are concerned with the trafficking of young men from their home countries to a place without laws and legislation to protect them. These workers effectively disappear into a system that critics have described as ‘modern-day slavery’. Their passports are taken. They are forced to work in dangerously hot weather. Many of them never return to their homelands, leaving their families destitute. Human rights and labour groups from around the world have researched this issue and have produced detailed and convincing reports enumerating the problems…

Oh?

What?!

You mean the ICSS is not talking about Qatar and the building of their World Cup infrastructure with tens-of-thousands of labourers under the controversial Kafala scheme? You mean that the 60 MinutesSport journalists have missed possibly the largest story of alleged wide-scale exploitation in international sport? You mean the ICSS executives did not look up from their desks in air-conditioned offices in Doha gaze out the windows and notice the problems of some of the foreign workers?!”

Interesting…

So what are the ICSS executives and the 60 Minutes Sports journalists drawing our attention to, if not the labour controversy in the city-state where they are headquartered? The issue that has drawn world-wide attention to the mistreatment of workers in Qatar?

Football players from Ghana being ‘trafficked’ to play for European teams.

I spoke to an expert on this issue, Professor Darragh McGee from the University of Bath. McGee, like myself, has been to Ghana. He has done impressive field work in gaining his doctoral thesis on exactly this subject. McGee, like many other experts, believes that the idea of ‘trafficked’ players from Africa is not completely accurate. McGee said, “Are there exploitative practices going on? Yes, but it is not a systematic problem with links to organized crime as many people make it out to be.”

To be clear, there is a problem of players – or people who hope to play – in European leagues coming from Africa and being mistreated. However, at most the numbers of people is in the hundreds a year. In Qatar, that is the number of labourers who might enter the country in a single day.

Let us also be very clear, the Qatari sport establishment is not the tobacco industry. The Qatari sport establishment are led by a group of misguided billionaires who have got themselves into a prison of cultural expectations. Hundreds of workers building their World Cup infrastructure may have died, thousands (numbers are not clear) may have been injured. Mohammed bin Hammam’s involvement with their World Cup bid may have been rife with corruption. However, for all the problems in Qatar, it is nothing like an industry which is turning out a product responsible for the premature death of tens-of-millions of people in the next few decades.

However, having made this necessary comparison, this 60 Minutes Sport story is reminiscent of the “problem” of Sick Buildings and the tobacco industry: a relatively minor problem is being promoted by a group that is helping to focus media attention away from their own, far larger, controversies.

That 60 Minutes Sport should, once again, have fallen for this kind of diversionary tactic exposes the state of their journalism. Come on, 60 Minutes Sport, remember The Insider – you can and must do better.