Last week, Samir Geagea, the Lebanese Forces leader, stated in a television interview that Lebanon’s political system could not continue as is. Parliament’s latest failure to elect a president led Geagea to declare, “[W]e conclude from today’s session that the Lebanese state cannot continue with its current structure and that we are in dire need of another structure that would rescue us from the swamp in which we have been languishing for years.”

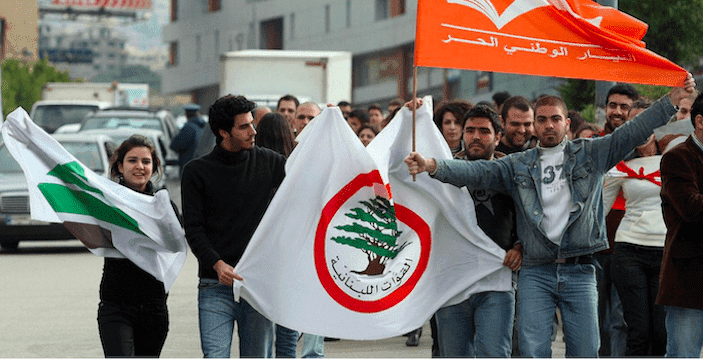

Geagea and other Christian leaders, including Geagea’s main rival Gebran Bassil, have begun expressing their support for a new type of order, whose underlying principle would be a less centralized system, one in which Christians would have more latitude to manage their own affairs. This has led Christians to discuss a range of options—from administrative decentralization, to both administrative and financial decentralization, to federalism, to partition. The practicality of each of these proposals varies, but the message in all of them is roughly the same: Christians no longer feel that political and social developments in Lebanon, and beyond that in the Middle East, favor their minority, and they want to break loose.

One can criticize certain dimensions of this attitude. Above all, that what is motivating Christians is less a desire to create a functional political and social system, than to formalize a divorce from Muslims under another name. If the primary aim is to agree to a permanent separation, the argument goes, then it is hypocritical of Christians to portray their attitude as an effort to reform the state. Christian leaders and publicists have yet to address this ambiguity in their position. However, it would be foolish to ignore the challenge their discontent presents.

The reality of the sectarian Lebanese social contract is that the Maronite community played a vanguard role in establishing modern Lebanon, which was consolidated through a historical compromise with the Sunni community in the National Pact of 1943. That compromise broke down in the 1970s, primarily because non-Christian communities began questioning the foundations of this pact, amid rapid social and demographic change that no longer justified Christian predominance. This was one of the causes of the civil war between 1975 and 1990. In a formal and brutal way, the conflict was resolved in 1989 through the Taif Agreement and the Syrian takeover of Christian-majority areas in October 1990. Taif redistributed many of the Maronite president’s powers to the Muslim sects.

It is no suprise then that Taif, which amended the constitution, is regarded by many Christians as a historical defeat. The Syrian military presence until 2005 only reinforced that sentiment, as leading Maronite leaders were either sent to prison or forced into exile. When the Syrian army and intelligence agencies departed in 2005, they were replaced by an equally complex problem—namely an armed Hezbollah that had no commitment to the National Pact and whose primary loyalty was to Iran and its supreme leader. Aoun allied himself with the party, believing this would win him the presidency. It was a clever tactical move that bore personal fruit, but ultimately it didn’t in any way reassure Christians about their prospects in Lebanon. From Syrian hegemony, the country had moved to Iranian hegemony by proxy.

As Christians look around them, they have fallen back on the fidgety reflexes of a minority that feels threatened existentially. Gone are the days of the Maronites’ self-confidence, which pushed them and their clergy after World War I to lobby for an expanded state encompassing many more Muslims, against the warnings of some coreligionists that the demographics would turn against Christians before long. From a community with broad horizons, the Christians have since followed one of two paths, both fatal for their communal future: they have either closed in upon themselves mentally and spiritually, or they have emigrated.

Yet as Christians lose faith in Lebanon’s communal social contract and withdraw, the outcome could be significant for the Sunni and Shia communities. Without an active Christian community, in many regards Lebanon would simply not be Lebanon. Moreover, absent the Christians in the middle, around which the two major Muslim sects can maneuver, Sunnis and Shia will have to deal directly with one another. That’s not a problem much of the time, but when it touches on sensitive national issues, as it will, such as Hezbollah’s weapons, it could push the two sides into a confrontation whose outcome would be difficult to predict.

Under normal circumstances, this situation would lead to a national discussion on ways to rework the system so its institutions are no longer used as impediments in a perpetual sectarian game of power. But with Hezbollah having the upper hand that’s not likely to occur. The party, because it doesn’t have any good options for its long-term role in Lebanon, has no incentive to reform a system whose shortcomings open up wide spaces to pursue its political agenda. Moreover, the party has never hidden its disdain for the National Pact, from which the Shia community was excluded. The paradox, however, is that Hezbollah, which sought to change the sectarian political order in the 1980s and early 1990s, today is one of its staunchest defenders, as its violent opposition to the October 2019 uprising proved.

Hezbollah will never engage in a serious dialogue on altering the Lebanese system precisely because such a discussion would lead to demands that the party surrender its weapons. There is Lebanon, and there is Hezbollah’s Lebanon, and in no way can the two coexist harmoniously for as long as the party retains its arms, which the other sectarian communities will always view as being directed against them.

What can the Christian community do about this? Above all, it has to grasp that its salvation lies not in the greater isolation of Christians from their surroundings, but less. If Christians want to preserve their place in Lebanon, they have to fight for what remains—clarifying their principles for what constitutes a workable Lebanese social contract, and not succumb to the sublime foolishness that greater seclusion will somehow bring greater security. Lebanon’s pluralism is inherently tied to a continuing Christian presence in the country, but Christians have to want this.

Ironically, Michel Aoun, who more than anybody facilitated Hezbollah’s takeover of the state after 2005, did something essential in showing Christians that they retained power despite Taif. Aoun is hardly an ideal model, let alone Geagea, both of whom devastated the Christians in 1989–1990. But after doing so much damage, the two men can compensate for this. Only Christians who remain engaged in shaping Lebanon’s destiny will have a say in the outcome. In contrast, those who build barriers around the community will be responsible for its demise.