Beirut bishop’s terse exchange with the country’s Maronite president echoes the Christian community’s unhappiness with the elite

In early February, on the occasion of Saint Maron’s Day – celebrating the founder of Lebanon’s Maronite Church, the spiritual authority of the country’s largest Christian community – the bishop of Beirut Paul Abdel-Sater, spoke at a mass in the presence of President Michel Aoun and other senior officials. The bishop’s remarks said a great deal about how the Maronite religious hierarchy views the months-long protests against the political class and its endemic corruption.

“Do the tens of thousands of Lebanese who elected you not deserve a correction to the political, economic and financial imbalance?” Bishop Abdel-Sater asked officials at the ceremony. “Does your conscience not move you at the sight of a mother wailing over her son, who committed suicide because he was unable to provide for his children?” He requested that the officials “work with the true revolutionaries [protesting the current situation]day and night” to resolve Lebanon’s crisis, “otherwise, the most honourable thing to do is to resign”.

The bishop’s remarks echoed widespread popular disgust with Lebanon’s politicians. Yet it was still unusual to see a Maronite clergyman so boldly take officials to task in public, in particular Mr Aoun, who is himself Maronite.

Yet there was good reason for Bishop Abdel-Sater doing what he did, at a time when the Maronite patriarch, Bishara Al Rai, has also supported Lebanon’s protest movement. The church is alarmed that the catastrophic social and economic situation the country’s political elite has caused is driving youths to leave the country. As a minority, Christians will be hit particularly hard by this trend.

The church is correct in regarding Lebanon’s problems as having existential implications for the country’s Christians, but also in many ways for Lebanon itself. Even the most optimistic estimates suggest that it will take years for the country to begin emerging from its current predicaments, which means many more young people will leave to go abroad – a process already well under way before the crisis began.

The irony is that Mr Aoun and his son-in-law Gebran Bassil have always portrayed themselves as purveyors of a Lebanese Christian revival. Yet a cursory look at the presidents’ record would indicate a very different reality. When he headed a military government in 1988-1990, Mr Aoun embarked on a pair of conflicts with the Syrian military, then with the Christian Lebanese Forces militia, which provoked a mass migration of Christians at the time.

Since then, the president and Mr Bassil have also contributed to creating a highly negative climate in the country that has again undermined confidence. With Hezbollah’s support, they blocked parliament and much of the political system for more than two years between 2014 and 2016 as blackmail for Mr Aoun to be elected president. That period was one in which the country was dangerously adrift, economic conditions deteriorated, and institutions ceased to function effectively.

Mr Aoun has rarely allowed Lebanon’s interests to interfere with his personal ambitions. However, for a president who has claimed to be a champion of Christians to be so explicitly criticised by a senior member of the Maronite clergy only confirmed the extent to which Mr Aoun’s presidential mandate has been perceived as a fiasco by all but the president’s most credulous supporters.

Christians are estimated at roughly 30 per cent of the Lebanese population, though a census has not been held since 1932. Some figures go higher. However, the reality is that the dysfunctional Lebanese system, dominated by a corrupt sectarian political class and a militarised party, Hezbollah, which follows an Iranian agenda, offers no appeal to many young Lebanese. When youths graduate, their first impulse is to leave the country to find work elsewhere.

These dynamics have been particularly damaging to Christians, given their lower demographics. The reason is that those who leave Lebanon usually do so permanently, because there are few interesting job opportunities open to them at home and the economy often fails to reward innovation and initiative. Moreover, given the sectarian leaders’ predatory lock on the political system, it is virtually impossible to break the prevailing status quo.

The Maronite church, though often seen as a bastion of rigid conservatism, has been an instrument of profound change in Lebanon’s history. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the church’s educational institutions were responsible for creating a class of educated people willing to challenge the prominent lordly families, thereby injecting social dynamism into the community against a feudal order.

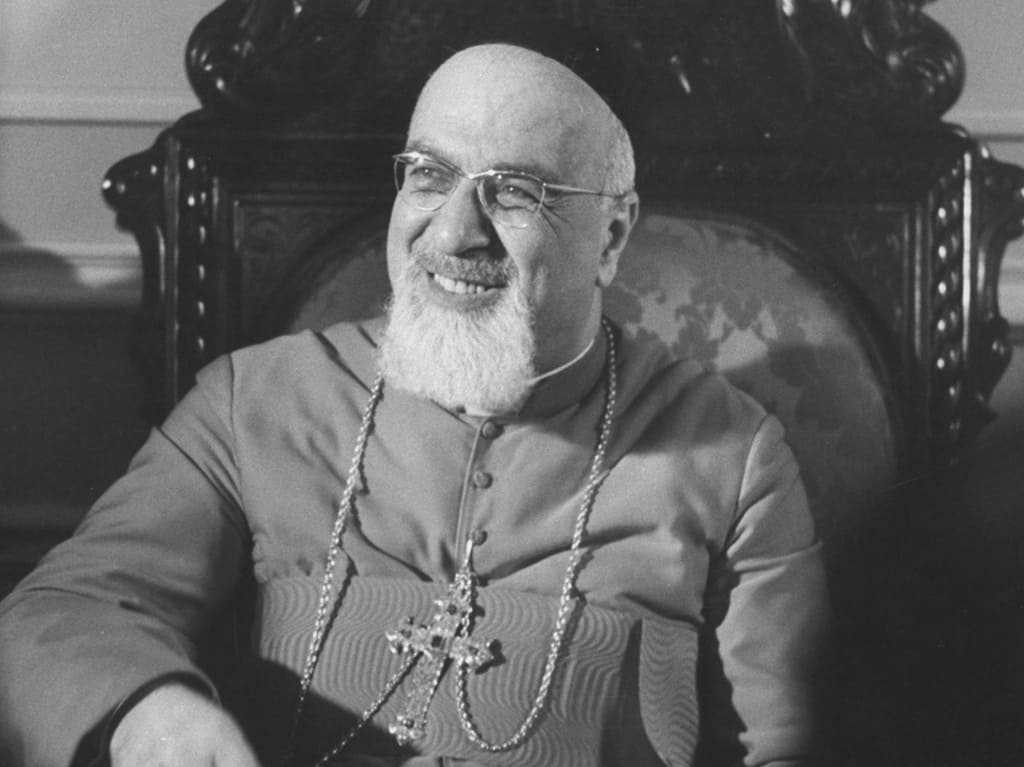

The Maronites were not the only church to do so, but the reality is that the clergy has not been systematically aligned with the political elite, or even with the Maronite president. For instance, during the civil war of 1958, the patriarch at the time, Paul Peter Meouchi, strongly opposed the president, Camille Chamoun. In other words, the Maronite church has a legacy of opposition to the political elite on which to build as it seeks to defend its community’s presence in Lebanon.

In his remarks, Bishop Abdel-Sater was making a fundamental point, namely that the Maronite community is not defined by the whims of its politicians. Yet all the signs today are that it is threatened by the folly of its most dominant leaders.

Michael Young is editor of Diwan, the blog of the Carnegie Middle East programme, in Beirut

THE NATIONAL