In light of its large Sunni population, the coastal city and its environs are not secure for the Syrian regime, possibly explaining why Russian forces are concentrating there.

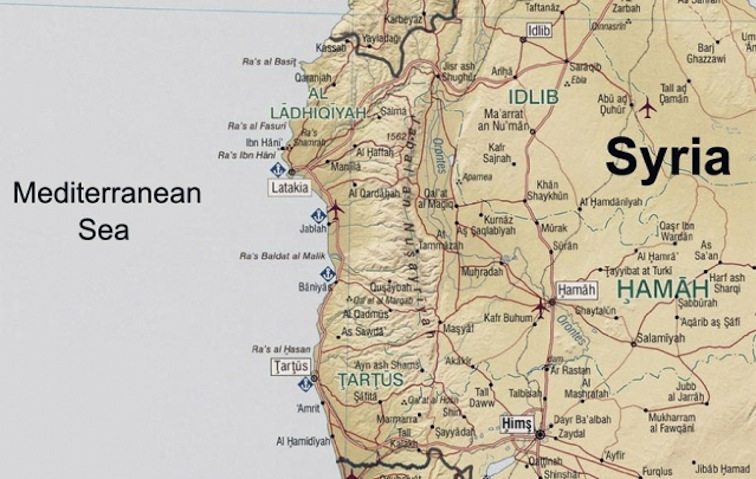

Over the past few months, the Syrian army has grown weaker and lost many positions, a development that explains Russia’s recent deployment of troops. Previously, Russia had sent only military advisors and technical staff to support the Syrian army. Another key question, however, involves why these troops are being sent to Latakia and not Tartus, site of the official Russian military base. Indeed, this new, strong Russian presence along the northern Syrian coast can be explained by the Assad regime’s weakness in the area, where Alawites no longer constitute a majority.

LATAKIA DEMOGRAPHICS

In 2010, the population of Latakia was about 400,000, about 50 percent of whom were Alawite, 40 percent were Sunni, and 10 percent were Christian — mostly Orthodox. Geographically, Alawites occupy the northern and eastern suburbs, whereas Sunnis live downtown and in the southern suburb of al-Ramel al-Filistini, the city’s poorest area. Christians inhabit what is known as the American district, named for an American-established Protestant school. In this historically Sunni city, Alawites are still considered by the old urban dwellers to be foreigners. Up until the French Mandate, which began in 1920, the city had no Alawite residents at all, except household servants. More than two decades later, in 1945, Alawites constituted only 10 percent of the population, living in a poor suburb called al-Ramel al-Shemali. A dramatic demographic shift, however, was encouraged by President Hafiz al-Assad’s policy of “Alawitization,” which led Alawites to become a majority by the 1980s.

(Note: The web version of this article includes maps illustrating various demographical and military data; see http://washin.st/1iM4ng7)

The countryside around Latakia is likewise divided between Sunni and Alawite villages. Traveling north toward Turkey along the Latakia-al-Haffah-Salma line, one finds a majority of Sunnis, according to the 2004 census — about 80,000 of the 140,000 residents. In particular, the subdistricts of Rabia and Qastal Maaf are mostly Sunni (Turkmen), as are the coastal villages of Burj Islam and Salib al-Turkman. Since the crisis began in 2011, the Turkmens of Rabia and Qastal Maaf have joined the armed opposition, whereas Turkmens from Burj Islam and Salib al-Turkman, surrounded by Alawite villages, have preferred to stay neutral. To the east of Latakia, the northern part of Jabal al-Ansariyya (Alawite Mountain), including al-Haffah, its surrounding villages, and Jabal al-Akrad (Kurds Mountain), is also Sunni-dominated. Even though the residents of Jabal al-Akrad are of Kurdish origin, dating to the Middle Ages, none of them speak Kurdish any longer and the area is considered effectively Arab. Since spring 2012, Jabal al-Akrad has been a rebel stronghold. That July, al-Haffah was occupied briefly by rebels coming from Jabal al-Akrad, but the population did not join them for fear of incurring government retaliation.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Latakia city is now hosting 200,000 internally displaced persons, along with 100,000 more IDPs elsewhere in the province. Most are Sunnis from Idlib and Aleppo. Alawites go to Alawite villages and Sunnis to Sunni areas, the result being an increase since 2011 in Sunni representation along the Latakia-al-Haffah-Salma line. Indeed, by now, most Sunni women and children residents of Jabal al-Akrad and the Rabia subdistrict have fled to Turkey, where they are living as refugees. Most of the men, however, are fighting against the Syrian army.

WEAKENED NORTHWEST FRONT

Since spring 2012, the armed opposition has controlled Jabal al-Akrad and the area along the Turkish border, up to the Armenian village of Kassab. In March 2014, jihadist groups, coming partly from Turkey, invaded Kassab and destroyed the Russian radar station atop Jabal Aqra. But, unable to progress southward, they left Kassab that June. To the west of Idlib, Jisr al-Shughour, and Ariha, a geographical continuum exists between Jabal al-Akrad and the northwestern rebel zone, posing a real threat to regime control in Latakia. This is why Syrian president Bashar al-Assad created a new militia, the “Shield of the Coast,” belonging to the National Defense Army. The specific goal is to protect the Syrian coast with young Alawites who have refused to fight outside the Alawite area. Assad needs to show he is protecting “Alawistan,” unless he wants Alawite soldiers to take matters into their own hands and renounce their government support. During July and August 2015, the rebel offensive in the al-Ghab plain threatened Latakia and the underpopulated Alawite villages in northern Jabal al-Ansariyya.

Given all these dynamics, the risk of a Sunni uprising in Latakia still exists. The Sunni suburb of al-Ramel al-Filistini has been surrounded by the Syrian army since the August 2011 uprising, and many residents are awaiting the right moment to act.

BATTLE FOR THE SEA

For the rebels, gaining access to the sea is both strategic and symbolic. The al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (JN), traveling from Kassab, reached the Mediterranean in just a few days. The new “Conquest Army” (Jaish al-Fatah), also headed by JN, would very much like to control a major port like Latakia or Tartus. The case for Latakia, from this perspective, is comparatively strong. To begin with, the road to Latakia is more accessible than the Tartus road. In addition, Tartus — as contrasted with Latakia — is a true Alawite city, with Alawites constituting 80 percent of the population, along with 10 percent Sunnis and 10 percent Christians. Moreover, the population residing between Tartus and Homs is predominantly Alawite, with a strong Christian minority (e.g., in Safita and Wadi al-Nasara). In the countryside surrounding Tartus, Sunnis are concentrated around al-Hamidiyah and Talkalakh. Complicating other jihadist roads to the sea are Hezbollah and the Syrian army, which are stiffly controlling the Lebanese border to prevent any coordination between Sunnis in Syria and the Sunni Akkar district and Tripoli. This strategy was exemplified by the al-Qusayr battle in May 2013.

Currently, Damascus and Homs are being protected by Hezbollah and other Shiite militias. Holding this territory is essential for the regime, Hezbollah, and their Iranian backers. Meanwhile, Latakia represents less of a strategic interest for Iran, as contrasted with Russia, which wants to maintain a presence along the coast more than in Damascus or the Golan Heights. Toward this end, the Russian navy still holds its base in Tartus and plans to rebuild the former Soviet submarine base in Jableh, some twenty miles south of Latakia. With the aim of bolstering a future Alawite state on the Syrian coast, whether it extends to Damascus or not, Russia is also fortifying its position along the southern Turkish border, with the ultimate goal of preventing Sunni Syrian forces from gaining access to the sea.

CONCLUSION

Given the rebels’ spring offensive near Idlib, a real possibility exists that the civil war will reach Latakia. A rebel army could find strong support from Sunni residents, many of whom have long dreamed of revenge for regime efforts to impose Alawite control over the city. After the April 2015 fall of Jisr al-Shughour, fear overtook the Alawite population, and some families fled for Jabal al-Ansariyya, which is considered more secure than Latakia, whose refugees’ loyalty to the government can hardly be assessed.

Many Russians are living in Latakia, and they understand very well the sectarian problem facing the city and countryside alike. As for the influx of Russian troops, they are needed to protect the city given the present weakness of Syrian forces. If the rebels succeed in taking all or part of the city, rooting them out would be extremely difficult. Such a takeover would challenge the Russian path forward, perhaps modeled on Abkhazia, the territory that now exists almost entirely independent of Georgia thanks to Russian protection — and that fits the Russian practice of grooming microstates on its periphery to serve as military bases. A Russian-backed Alawistan, should it become viable, would provide many of the advantages of a real state, including complete dependence on Russia, without the same costs.

For his part, Assad has no better choice than to accept a strong Russian role in the coastal region. His army can no longer defend Latakia, which faces the prospect of a rebel offensive strongly supported by Turkey. Nor can Assad defend Damascus without the support of Hezbollah and Iran. Western and Gulf countries have long counted on the possibility that a weakened Syrian army and Assad’s eventual overthrow could allow for an imposed political transition, but this plan did not account for direct Russian intervention or, should Damascus come under threat, direct intervention from Iran.

From the French perspective, continued bombardments against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, or ISIS, will continue to be carried out in the name of self-defense, given that recent terrorist attacks perpetrated in France seem to have been planned in Syria. France will thus be loath to deny the Russians their efforts on the ground in Syria, also officially to fight terrorism. Other Europeans will be compelled to take a similar view of the Russians, who by sending troops to an Alawite area will also appear, in concrete terms, to be protecting Middle East minorities and not just organizing conferences such as the one held by French foreign minister Laurent Fabius earlier this month.

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.