Dr. Mohamed Helmy, an Egyptian-born physician, hid four Jews in Berlin for the duration of World War II

Ofer Aderet

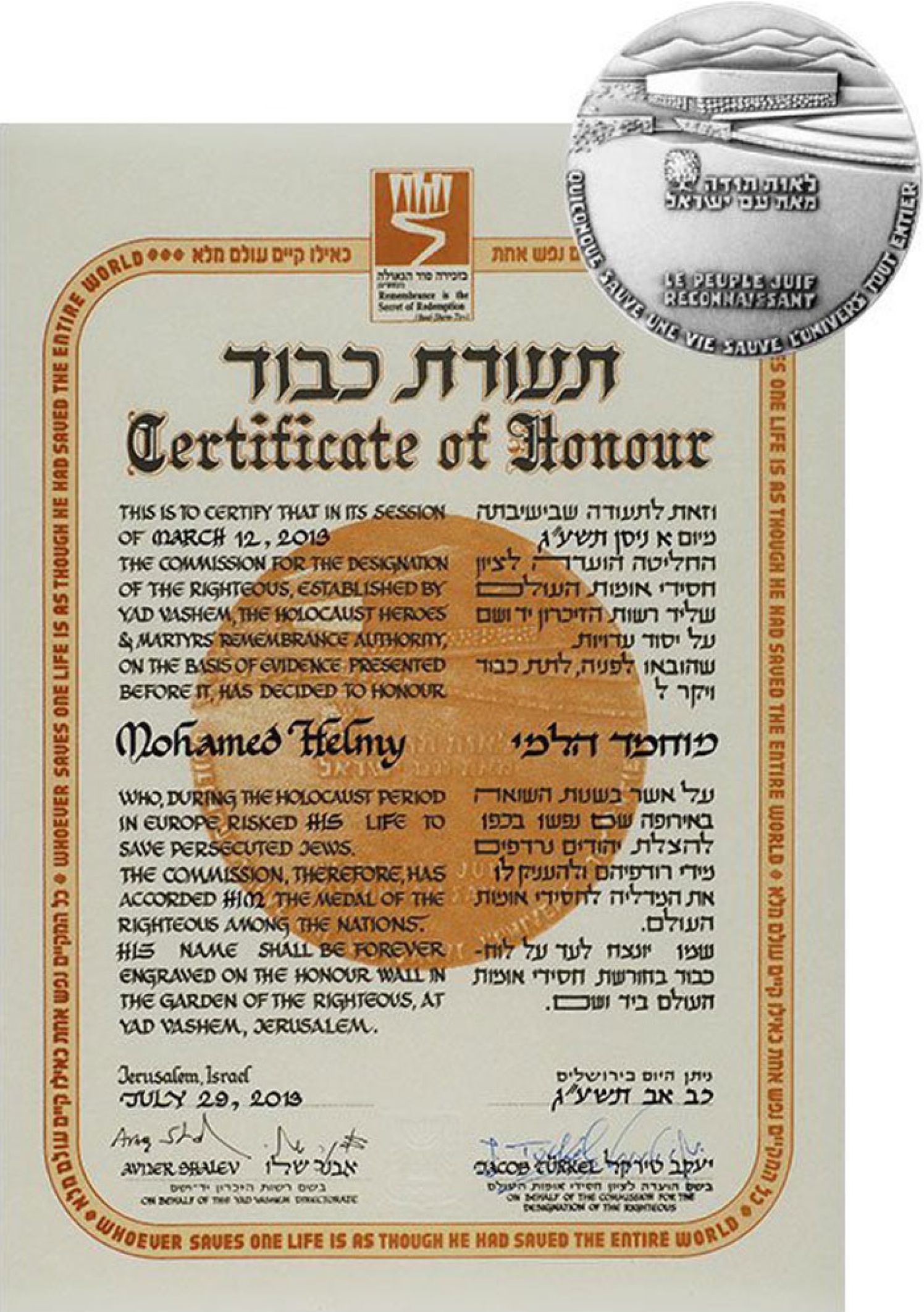

Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial center will for the first time recognize as “Righteous Among the Nations” an Arab who saved the lives of Jews during the Holocaust. The family of Dr. Mohamed Helmy will accept the award from Israel’s Holocaust memorial and museum in a ceremony in Berlin on Thursday.

Helmy, an Egyptian-born doctor living in Berlin, risked his life when he sheltered four Jews throughout the period of World War II.

Yad Vashem recognized Helmy, who died in 1982, as Righteous Among the Nations in 2013, but his family initially refused the honor because the institution is Israeli.

“If any other country offered to honor Helmy, we would have been happy with it,” said Mervat Hassan, the wife of Helmy’s grandnephew, told The Associated Press during an interview at her home in Cairo in October 2013. Now, after a four-year search, a relative was found who agreed to accept the award.

Nasser Kutbi, an 81-year-old professor of medicine from Cairo whose father was Helmy’s nephew and who knew him personally, will travel to Berlin to accept the award.

Israel’s Ambassador to Germany, Jeremy Issacharoff will present the certificate and medal to Kutbi. The ceremony will be held at the German Foreign Ministry rather than at the Israeli Embassy in Berlin, in part because Helmy’s family still has reservations about accepting the award directly from an Israeli institution.

Helmy was born in Khartoum in 1901, in what was then Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. He went to Germany to study medicine in 1922, settling in Berlin. After completing his studies, he was hired by the Robert Koch Institute in the city, where he eventually became head of urology. Helmy saw Jewish doctors fired from the hospital in 1933, after the Nazis came to power, and was himself fired in 1937. A 2009 study by the institute showed that it was heavily involved in Nazi medical policy.

According to Nazi racial theory, Helmy was considered Hamitic (that is, descended from Noah’s son Ham). As a “non-Aryan,” Helmy was barred from working in the public health system and was also not allowed to marry his German fiancée. In 1939 Helmy was arrested by the Nazis, together with other Egyptians, and was released after a year due to ill health.

When the Nazis began deporting Jews from Berlin, he hid Anna Boros, 21 and a family friend, in his cabin in the city’s Buch neighborhood. She remained there for the duration of the war. Whenever Helmy was under police investigation, would arrange for her to hide elsewhere. Anna lived as a Muslim under an assumed name, wore a hijab and even married a Muslim in a fictitious marriage.

“A good friend of our family, Dr. Helmy … hid me in his cabin in Berlin-Buch from 10 March until the end of the war. As of 1942, I no longer had any contact with the outside world. The Gestapo knew that Dr. Helmy was our family physician, and they knew that he owned a cabin in Berlin-Buch,” wrote Boros, who went on to marry and take the last name of her husband, Gutman, after the war.

“He managed to evade all their interrogations. In such cases he would bring me to friends where I would stay for several days, introducing me as his cousin from Dresden. When the danger would pass, I would return to his cabin. … Dr. Helmy did everything for me out of the generosity of his heart and I will be grateful to him for eternity.”

Helmy also helped Gutman’s mother Julie, stepfather Georg Wehr and grandmother Cecilie Rudnik. Providing for them and attending to all their medical needs, he arranged for Rudnik to be hidden in the home of a German woman, Frieda Szturmann, who was herself later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. For over a year, Szturmann hid Rudnik, sharing her meager food rations.

But the family was caught in 1944; during their brutal interrogation they revealed that Helmy was helping both them and Gutman. Helmy immediately brought Gutman to Szturmann’s home; only his keen resourcefulness kept him out of trouble.

After the war, the four family members emigrated to the United States but did not forget their rescuers; in the 1950s and early ‘60s they wrote letters to the Berlin Senate lauding them. These letters were uncovered in the Berlin archives and were submitted to Yad Vashem. They also visited Helmy a number of times in Berlin over the years and remained in contact.

Helmy remained in Berlin after the war, continued to work as a doctor and was finally able to marry his fiancée. They had no children and remained in Germany.

“They did not want to have children for fear of the wars,” Mervat Hassan, the wife of Helmy’s grandnephew, told the AP in an interview at her home in Cairo in 2013. “They did not want them to see the horrors of war.”

Helmy died in 1982; Frieda Szturmann died in 1962 and Gutman died in 1986. Helmy’s wife died in 1998.

In 2013, when Yad Vashem recognize Helmy and Szturmann as Righteous Among the Nations they tried to locate Helmy’s relatives, and even turned to the Egyptian Embassy in Israel and the press.

The Associated Press located a relative in Egypt who refused to accept the award. Other relatives explained to German historian and journalist Ronen Steinke why they refused: Yad Vashem is political institution representing Israel and has no right to represent Jews everywhere, they said. In addition, Israel was not founded until 1948 and did not exist at the time Helmy carried out his actions, so today Israel has no right to represent the Jewish victims of that period, they added. They also criticized Israeli policy toward Palestinians, saying one of their relatives had died in one of the wars between Israel and Egypt.

Helmy’s relatives feel he saved Anna not because she was Jewish but because she was a human being and the attempt to recognize him for saving Jews is inappropriate, Steinke told Haaretz.

It is not yet clear why Kutbi has agreed now to accept the award, but Israeli documentary filmmaker Taliya Finkel, who has made a film about Helmy: “Mohamed and Anna – In Plain Sight,” was involved.

Steinke met with Kutbi in Cairo. Kutbi is active in fighting anti-Semitism in Egypt and remembers the good relations between Jews, Muslims and Christians last century, says Steinke. He spoke with longing of the glorious past of the Jews in Egypt and mentioned how many famous Jews there were in Egyptian politics and culture. Kutbi also said that one of his cousins was married to a Jewish woman, who owned a fashionable clothing store in Cairo, said Steinke.

Steinke published a book this year: “The Muslim and the Jew” (in German) about Helmy’s story. At the end of the book he quotes a letter from Anna’s daughter Carla, who lives in New York, to Helmy’s relatives in Egypt thanking him. He passed on the letter to the family in Cairo, but as of today, over a year later, they have not yet replied.

Yad Vashem has recognized some 26,000 Righteous Among the Nations from 44 countries and nationalities so far. A few dozen are Muslims, including from Albania, the Caucasus and the Balkans. But Helmy was the first Arab so recognized.

Until the next of kin were found, Helmy’s certificate and medal were on display in Yad Vashem.