Whether or not Tehran is proven to be involved, the incident holds significant implications for the regime’s international diplomacy and terrorist activity—not to mention its claims about the applicability of Khamenei’s “nuclear fatwa.”

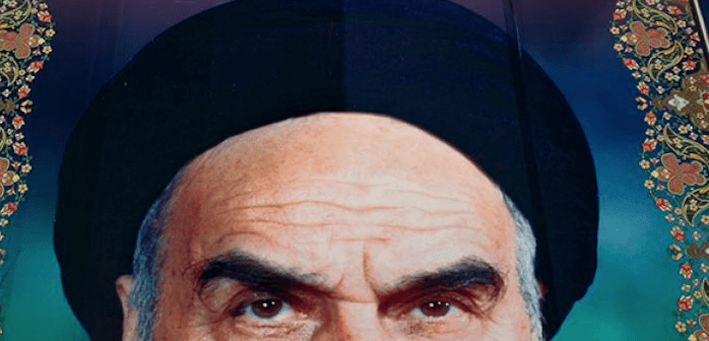

The August 12 assassination attempt against Salman Rushdie reveals a great deal about the Iranian regime’s current mindset, particularly when one takes a close look at Tehran’s initial response. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and other senior officials have remained largely silent about the attack so far, while Foreign Ministry spokesman Nasser Kanaani denied any Iranian involvement during a press conference earlier today. At the same time, however, multiple regime-affiliated media outlets—and Kanaani himself to a certain extent—have explicitly praised the attack and expressed admiration for its perpetrator, Hadi Matar, portraying him as a true follower of the Islamic Republic’s founder, Ruhollah Khomeini.

On August 14, Kayhan newspaper—owned by Khamenei and run by his representative Hossein Shariatmadari—addressed the issue in an article headlined “Salman Rushdie Trapped in Divine Revenge: Trump and Pompeo Are Next Targets.” The story goes on to suggest that the attack on “the apostate author…who insulted the prophet of Islam” should be regarded as an Iranian response to the Trump administration’s targeted killing of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) general Qasem Soleimani in January 2020. The article then offered the following threat: “We should not remain passive and commit miscalculation…The response to animosity cannot be wishful thinking, passiveness, and flexibility…The attack on Salman Rushdie proves that getting revenge against criminals on U.S. territory is not difficult, and from now on Trump and [his former secretary of state Mike]Pompeo will find themselves under more serious threat.”

Similarly, the official government newspaper Iran claimed that “the big message” of Matar’s attack is clear—Muslims still hold great “love in their hearts for the prophet of Islam,” and not even the passage of many years has diminished their anger at “insults and mockeries” from Europe and the wider West. According to the article, the perpetrator who “implemented” Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death was “a twenty-four years young Muslim,” representing “a new phenomenon that reveals how faith in divine orders is still alive and well in the heart of the modern world.” (The question of whether this edict was truly a fatwa is discussed at length in the next section.)

The same day, the headline “The Unseen Arrow” appeared in Javan, a newspaper affiliated with the IRGC (with “unseen” implying “divine” in this context). This story likewise praised Matar as “a young Muslim who was not born until after Rushdie published The Satanic Verses” but nevertheless sought revenge for Rushdie’s “crime.”

For its part, Jam-e Jam—the official newspaper of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), an increasingly influential agency under Khamenei’s direct supervision—published a front-page article titled “The Satan’s Eyes Are Blinded.” The story then proudly supported the attack, claiming, “In reality, the act of terror against Rushdie after thirty-three years proves that the power of the Truth to get revenge on Untruth transcends time and place.”

Khomeini’s “Fatwa”

The late ayatollah’s infamous 1989 order to murder Rushdie and his publishers has long held essential ideological value for the regime, especially as a symbol of its self-claimed leadership over the Muslim umma (community) and the success of its pan-Islamic agenda. At the time it was issued, however, the government of President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani desperately needed to establish economic relations with Europe in order to reconstruct its economy following the devastating war with Iraq. Thus, when Khomeini died just months after issuing the fatwa, the regime sought a deceptive formulation that would enable it to normalize relations with parts of the West without submitting to international demands for repealing the fatwa.

Upon succeeding Khomeini, Supreme Leader Khamenei and Rafsanjani agreed on how to resolve the dilemma: by claiming that there was a distinction between Khomeini as a marja (source of emulation) who issues fatwas for his religious followers, and Khomeini as head of the Iranian government. Using this formulation, Tehran could claim to Europe that the Rushdie fatwa was not necessarily the state’s official position, and that the government had no intention of implementing it—even though the state still refused to publicly reject the edict, government propaganda organs continued promoting it, and Khamenei kept reiterating it as the new de facto head of state (in fact, one of his affiliated foundations, Panzdahom-e Khordad, increased the bounty on Rushdie’s head to $3.3 million in 2011).

This disingenuous argument was largely effective—Rafsanjani succeeded in resuming relations with Europe, while Khamenei’s public remarks kept the fatwa alive in subsequent years. In one speech, for example, he declared, “It’s been a long time since [the fatwa was issued]. That ignorant [Rushdie] and his ignorant followers suppose that it is over! Not at all. There is no end for this issue.” In other speeches he made clear that the fatwa was “unchangeable.”

This supposed immutability—and, indeed, the origins of the fatwa itself—illustrate the regime’s deceitful use of Rushdie as an ideological pawn. The entire saga also casts a glaring light on Tehran’s willingness to exploit religious sentiment and law for political purposes, including in the nuclear realm.

For one thing, it is a matter of consensus among Muslim jurists (including Shia) that fatwas can be changed under specific conditions. Khamenei’s insistence that the Rushdie order has “no end” is therefore false even on basic religious terms.

Second, several factors indicate that Khomeini’s fatwa was not technically a fatwa:

- It is the only fatwa for which there is no proof that he wrote it down as a formal religious order; it was only announced by state radio.

- There is no religious or juridical basis for such a fatwa in the history of Islamic jurisprudence, as explained by prominent mujtahids (jurists) such as Mehdi Haeri Yazdi in his book Philosophy and Government (Hekmat va Hokoumat)

- Khomeini was unable to read English, Rushdie’s book had not been translated into Persian at the time, and the Supreme Leader was never known to read novels of any kind regardless, so he could not have issued the “fatwa” as a carefully considered religious response to an offensive text; rather, it was simply a political decision he made in service of his ideological objectives, and Khamenei has perpetuated it for the same reasons.

Third, Shia jurists also agree that a Muslim cannot follow a dead mujtahid unless he was a follower before the jurist’s demise. Hadi Matar is obviously far too young to have followed Khomeini during his time, so he should not be religiously authorized to implement a fatwa issued by the late leader.

These points reverberate far beyond Rushdie’s personal safety, especially when one recalls that the regime has spent years trumpeting another key fatwa: Khamenei’s edict prohibiting the production or use of nuclear weapons. Iran’s past and present nuclear negotiators have often insisted that the regime is a religious republic ruled by the Supreme Leader as the chief Shia jurist, so his fatwas are therefore the main basis for Iranian decisionmaking on major policy issues. Yet by demanding that the international community regard Khamenei’s fatwa as a reliable guarantee of Tehran’s supposed uninterest in militarizing its nuclear program, the regime completely contradicts its insistence that the Rushdie fatwa is not state policy.

Terrorism and Totalitarianism

Years’ worth of statements by the Supreme Leader and other Iranian officials show how they take pride in portraying the regime as a totalitarian government with a pan-Islamic agenda. Khamenei is almost never mentioned in state media without the sobriquet “the leader of the Muslim world.” And according to the Islamic Republic’s official rhetoric, the power that enables this all-encompassing leadership is the “power to terrorize and destroy.” For instance, the regime’s “regional power” is often expressed in terms of Iran’s supposed power to annihilate Israel. Likewise, “Victory by Terror” is the explicit leading strategy that Khamenei has repeatedly spelled out.

Tehran’s latest rhetoric about Rushdie reflects the same mindset, insisting to listeners that the regime is fully capable of threatening its American, Muslim, or Iranian opponents even on U.S. territory. Khamenei still perceives America as his enemy par excellence, so he is keen on convincing Americans that their personal security is at risk—one of many ways in which he seeks to counter and soften U.S. policies aimed at curtailing Iran’s destabilizing regional strategy. In his view, globalizing such terror (increasingly with the help of foreign operatives) is necessary in order to prove that his regime is the real “superpower” in the fight against the West. Policymakers should be careful not to forget the apocalyptic mindset that undergirds much of this rhetoric, whether one is talking about assassination attempts against lone activists, provocative regional military strikes, or, most important of all, nuclear brinkmanship.

Mehdi Khalaji is the Libitzky Family Fellow at The Washington Institute.