Societies divided along sectarian lines can be volatile affairs. In the Lebanese case, the sectarian communities are all, in one way or another, minorities, each with its existential fears. If other sects gain too much power, a sect’s instinctive reaction is to anticipate its own elimination. Often this can lead to war, as a fearful minority overinterprets the actions of rivals, and prepares to fight for what it regards as its survival. This is what happened in the period before the civil war in 1975, when Maronite political parties began arming. They viewed the growing strength of Palestinian military groups as a factor decisively favoring the Sunni community, believing this threatened their own place in the state, and ultimately their presence.

Sectarian systems tend to sanction sects that try to impose their will on the others. When the Palestinians left Lebanon, in 1982 and then more conclusively in 1983, the Sunnis lost their main military prop and faded for years. The Maronites thought they could impose their supremacy through Israel’s invasion of 1982, but this was undermined by Israeli reluctance to become entangled in Lebanese enmities, hostility to Maronite ambitions from other sects, and military aid provided to these opponents by foreign countries. The result was a major loss of Maronite power once the war ended.

Today, a more complicated situation prevails with the Shia community, or that part of it that endorses Hezbollah. The party is heavily armed, but its foreign sponsor, Iran, is not physically present in Lebanon, so there is no real option of forcing its departure to weaken Hezbollah. On the contrary, the Iranians anchored their regional project in the wreckage of Arab discord—in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen—not in open-ended military deployments. This has led many people to wonder what can be done to put an end to Hezbollah’s hegemony, short of initiating a civil conflict that would ruin the country and very likely resolve nothing. The simple answer is that nothing can be done at the moment.

However, that does not mean there is no way of placing limits on the party’s margin of maneuver. And here it may be useful for the Lebanese opposed to Hezbollah to build upon wider foreign involvement, the very poison plaguing their country since independence. If Lebanon again becomes an open field for regional and international competition, there could be a latitude to set limits to what Tehran and its allies do and turn the country into a place of negotiation, as opposed to its remaining an exclusive Iranian satellite.

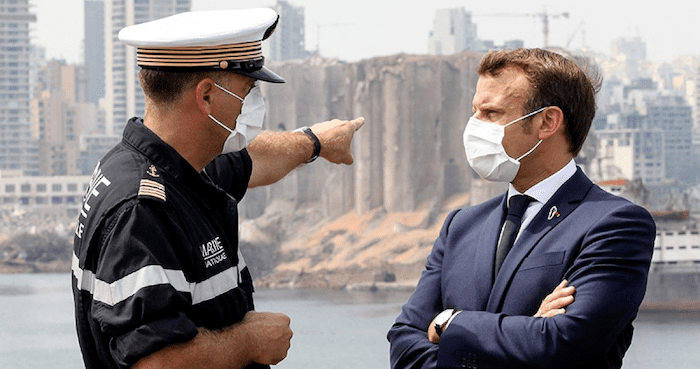

In many regards we’ve seen the beginning of this during the past year, as Lebanon’s economic collapse and the Beirut port explosion have invited outside concern. The explosion allowed French President Emmanuel Macron to enter the Lebanese scene with gusto. His initiative was later neutralized, but it also turned France into a recognized player in the country. The French were central to the government formation process, and will doubtless take the lead in any European effort to help Lebanon’s economic recovery.

The electricity crisis opened the door to an Egyptian and Jordanian initiative as well, supported by the United States, to supply Lebanon with energy and alleviate its disastrous economic situation. The belief among these countries is that Hezbollah and Iran would benefit from a full social and economic breakdown. The willingness of Lebanese to accept cheap Iranian fuel in recent months has proven this.

Similarly, the efforts by certain Arab states—the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Jordan—to begin normalizing with the Assad regime in Syria, is partly seen by them as a way of bolstering the country with respect to Iran. This could have definite repercussions on Iranian power in Lebanon if the Syrians attempted to revive their influence and networks in the country, this time supported by Russia.

On the other hand, the decision of some Gulf countries to cut Lebanon off has led nowhere. The latest decision to target the country in the aftermath of comments by Information Minister George Qordahi—comments he made before he was a minister—was a case in point. The statement of Saudi Foreign Minister Faysal bin Farhan earlier this week raised more questions than answers. He declared that it was up to the political class to “liberate Lebanon from Hezbollah and Iran.” Meanwhile, the Saudis saw no impetus to communicate with the Lebanese government “for the time being.”

No doubt the Saudis and other Gulf states are legitimately fed up with the Lebanese political class, given that so many politicians have taken advantage of Saudi and Gulf largesse, for little return. But how does Prince Faysal propose that Lebanon liberate itself, short of war? It is a country where a clear majority of the population rejects Iran’s agenda. But when the Gulf states fail to make the most of this and their isolation of Lebanon only facilitates Hezbollah’s efforts to dictate the country’s direction, how does this qualify as a successful policy? Normally, in politics one struggles for power, one doesn’t pout.

No one should expect clear or rapid outcomes from the foreign countries seeking stakes in Lebanon. Hezbollah and Iran will fight tooth and nail for every inch of terrain—witness the Iranian foreign minister’s recent efforts to torpedo a French plan to rebuild Beirut port, by offering that Iran do the same and more. Change will require patience by states to use their advantages, while accepting that zero-sum expectations will fail: Eliminating Iran’s sway from Lebanon will not happen, given the large Shia community there. With time, a regional consensus over the country may emerge to stabilize things, similar to the Syrian-Saudi understanding over the Taif agreement.

The Lebanese may groan at such a warmed over outcome, as well they should. Unfortunately, the country has not shown any of the unity necessary to avoid those kinds of solutions. Unless, and until, the population is unified, Lebanon will remain a football in other people’s matches. So, for the moment, it is preferable to exploit that shortcoming to prevent the country from being solely an Iranian tool, which would only reinforce the Arab quarantine imposed on it and even bring wholesale destruction in the event of a war with Israel.

Lebanon’s people was never unifed cause in Lebanon no Lebanese people but peoples sharing a land.