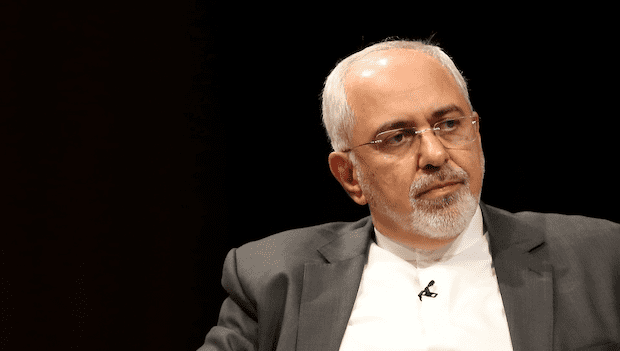

Foreign Minister Javad Zarif charms Western diplomats, while protecting the theocracy in Tehran.

(Published by The Atlantic on

When Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif tried to quit last week, the move looked like another troubling defeat for his country’s beleaguered moderates. Highly intelligent, sophisticated, and U.S. educated, Zarif always made an unlikely chief diplomat for the world’s most anti-American regime. Totalitarian governments, wrote Hannah Arendt, “invariably replace all first-rate talents, regardless of their sympathies, with those crackpots and fools whose lack of intelligence and creativity is still the best guarantee of their loyalty.” Zarif defied that mold, and Western officials and analysts feared that his departure would sever Tehran’s last link to the West.

In fact, he wasn’t going anywhere. Iran’s revolutionary elite, including Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, quickly rejected Zarif’s resignation. The foreign minister was soon back on the job, raising once again the question of what role an urbane functionary really serves in an autocratic regime.

To his admirers, Zarif is a skillful diplomat and fierce nationalist in constant danger of hard-line domestic adversaries. To his detractors, he is a pathologically dishonest, powerless apparatchik used by Tehran’s theocratic elite to manipulate credulous Americans and Europeans. To Khamenei, Zarif’s enormous utility derives from the fact that he is both of these things, a sympathetic figure who can soften the edges of Iranian policy without actually changing it. Just as Leonid Brezhnev had Andrei Gromyko, Saddam Hussein had Tariq Aziz, and Muammar Qaddafi had Moussa Koussa, Iran’s autocrats understand that sending a moderate emissary out in the world protects their own power, rather than undermining it.

Ifirst met Zarif in 2003, when he was Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, and I regularly interviewed him while working as an analyst with the International Crisis Group. He was unique among Iranian officials—astute, accessible, and affable—and openly engaged with diaspora Iranians like me, rather than treating us as a potential danger. When Iranian authorities confiscated my passport in 2005 and prohibited me from leaving the country, he offered helpful connections to get me out. When my employer wanted me to return to Tehran, I asked Zarif to check my file. “Under no conditions go back!” he urged me, days later. “The problems will start as soon as you arrive at the airport.” Absent his candor, I would have ended up like many friends and colleagues who spent months or years in Evin Prison.

I often wondered back then whether Zarif’s occupation ever gave him a crisis of conscience. Why would someone with his family wealth and education—a doctorate in international relations from the University of Denver—and seemingly cosmopolitan outlook represent an Islamist theocracy that treats women as second-class citizens, persecutes gays and religious minorities, represses free speech, and is the world’s No. 1 per capita executioner? In face-to-face meetings, he sometimes lamented to me that he chose a career in politics over academia.

When the Holocaust-denying Tehran Mayor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became Iran’s president in 2005, Zarif sounded like a Paykan salesman in Manhattan, grudgingly selling a product he knew to be bankrupt. I attended his farewell reception at the United Nations in 2007, offering him a gift of pajamas now that his work-induced sleep-deprivation would be ending.

After several years in political hibernation teaching graduate students in Tehran, Zarif saw his fortunes abruptly changed following the surprise victory of Hassan Rouhani, a pragmatic cleric, in Iran’s 2013 presidential elections. Zarif became Iran’s foreign minister and Tehran’s lead negotiator in multilateral nuclear-nonproliferation talks. When a nuclear deal—known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—was signed after two years of exhaustive diplomacy, Zarif became a national hero in Iran and a Nobel Peace Prize nominee.

At the time, there was a widespread hope that the goodwill developed between Zarif and then–Secretary of State John Kerry could foster greater regional cooperation between Washington and Tehran and lead to an eventual rapprochement. What was poorly understood then, and now, was the nature of Zarif’s job as foreign minister of the Islamic Republic of Iran. When this role required him to negotiate a nuclear deal to rid Iran of economic sanctions, he delivered. But when this role also required him to embrace war criminals, lay wreaths for notorious terrorists, defend hostage taking, deny Iran’s attempted assassinations in Europe, and lie about repression, Zarif also delivered.

Understanding Zarif requires an understanding of the bipolar nature of the Iranian regime. The Iranian officials who talk to Westerners have little power, and the most powerful officials, such as Khamenei and the Revolutionary Guard commander Qassem Soleimani, won’t talk to us. Khamenei has not left Iran for 30 years. Soleimani operates in the shadows, between Beirut and Moscow. This bipolarity affords Zarif plausible deniability. He can claim credit for Tehran’s constructive diplomatic initiatives, and deflect accountability for or knowledge of its malign actions.

Indeed, Zarif privately portrays himself as a target of the regime he represents. In a meeting in New York shortly after he became foreign minister in 2013, an exiled Iranian journalist asked Zarif whether he could help him visit his cancer-stricken mother in Tehran before she died. Zarif demurred. “Every time my plane lands in Tehran,” he said, “I wonder whether I will be permitted to leave the country again.” As a former senior U.S. nuclear negotiator told me, Zarif shrewdly invoked this sense of personal insecurity in meetings with Western counterparts, who sought to offer him concessions to protect him from the wrath of Iranian hard-liners.

Yet the perception of Zarif as a vulnerable moderate only makes him more valuable to Khamenei. Iran is perhaps the only country in the world simultaneously fighting three cold wars—with Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United States—and Khamenei manages these conflicts with two crucial tools. Soleimani serves as Khamenei’s sword, projecting Iranian hard power in the Middle East’s most violent conflicts. Zarif, in contrast, serves as Khamenei’s shield, using his diplomatic talents to block Western economic and political pressure and counter pervasive “Iranophobia.” The two men understand their complementary roles, and the division of labor between them: Soleimani deals with foreign militias, Zarif with foreign ministries.

Zarif has managed to effectively co-opt and convince many European officials and Iranian diaspora analysts and journalists, many of whom cover the foreign minister admiringly and take personal offense when he is criticized. Yet he could not have survived four decades as an official in an authoritarian regime had his fidelity to the revolution ever wavered.

Zarif’s willingness to tell brazen untruths with great conviction evokes a statement that another senior Iranian, Mohammad-Javad Larijani, once made to Elaine Sciolino of The New York Times: “Being able to keep a secret even if you have to mislead is considered a sign of maturity. It’s Persian wisdom. We don’t have to be ideal people. Everybody lies. Let’s be good liars.” Iran’s dishonest religious theocracy purports to fight global injustice from a moral pedestal. This hypocrisy has earned opprobrium for Zarif, spawning the hashtag #Zarifisaliar.

Though Zarif’s short-lived resignation was dramatic stagecraft, it did nothing to alter the fundamentals of Iranian statecraft. As long as the Islamic Republic faces internal and external insecurity—a near constant since 1979—Iran’s security forces will continue to overpower civilian institutions like the Foreign Ministry.

Consequently, regardless of when Zarif’s career as a diplomat is finally over, his legacy will eventually boil down to a simple question: Did he serve to restrain or enable the Islamic Republic’s internal repression and external radicalism?

While the complicated answer is that he does both, Zarif’s considerable diplomatic talents, coupled with his lack of authority, have meant that history will more likely remember him as more an enabler rather than a restrainer. “The sad truth,” Hannah Arendt wrote, “is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”