The prime location, secured by the Russian state after years of lobbying by the Kremlin, is so close to so many snoop-worthy places that when Moscow first proposed a $100 million “spiritual and cultural center” there, France’s security services fretted that Russia’s president,Vladimir V. Putin, a former K.G.B. officer, might have more than just religious outreach in mind.

A service for Russians killed in the Bastille Day terrorist attack at St. Nicholas Orthodox Cathedral in Nice, France. CreditAndrew Testa for The New York Times

A service for Russians killed in the Bastille Day terrorist attack at St. Nicholas Orthodox Cathedral in Nice, France. CreditAndrew Testa for The New York Times

Anxiety over whether the spiritual center might serve as a listening post, however, has obscured its principal and perhaps more intrusive role: an outsize display in the heart of Paris, the capital of the insistently secular French Republic, of Russia’s might as a religious power, not just a military one.

While tanks and artillery have been Russia’s weapons of choice to project its power into neighboring Ukraine and Georgia, Mr. Putin has also mobilized faith to expand the country’s reach and influence. A fervent foe of homosexuality and any attempt to put individual rights above those of family, community or nation, the Russian Orthodox Church helps project Russia as the natural ally of all those who pine for a more secure, illiberal world free from the tradition-crushing rush of globalization, multiculturalism and women’s and gay rights.

Thanks to a close alliance between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Kremlin, religion has proved a particularly powerful tool in former Soviet lands like Moldova, where senior priests loyal to the Moscow church hierarchy have campaigned tirelessly to block their country’s integration with the West. Priests in Montenegro, meanwhile have spearheaded efforts to derail their country’s plans to join NATO.

But faith has also helped Mr. Putin amplify Russia’s voice farther west, with the church leading a push into resolutely secular members of theEuropean Union like France.

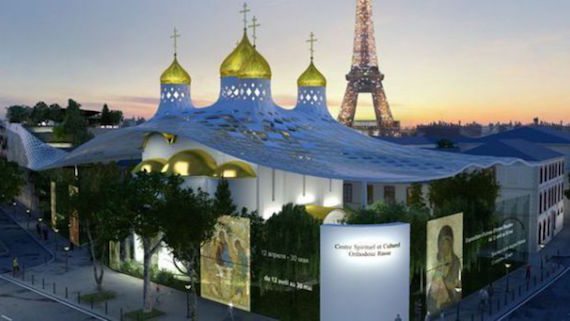

The most visible sign of this is the new Kremlin-financed spiritual center here near the Eiffel Tower, now so closely associated with Mr. Putin that France’s former culture minister, Frederic Mitterrand, suggested that it be called “St. Vladimir’s.”

But the Russian church’s push in Europe has taken an even more aggressive turn in Nice, on the French Riviera, where in February it tried to seize a private Orthodox cemetery, the latest episode in a long campaign to grab up church real estate controlled by rivals to Moscow’s religious hierarchy.

“They are advancing pawns here and everywhere; they want to show that there is only one Russia, the Russia of Putin,” said Alexis Obolensky, vice president of the Association Culturelle Orthodoxe Russe de Nice, a group of French believers, many of them descendants of White Russians who fled Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. They want nothing to do with a Moscow-based church leadership headed by Kirill, patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, a close ally of the Russian president.

A Broader Push

The French Orthodox association is instead loyal to the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, a rival church leadership in Istanbul that has provided a haven for many of Mr. Putin’s churchgoing foes. After a long legal battle with Moscow, Mr. Obolensky’s association in 2013 lost control of Nice’s Orthodox cathedral, St. Nicholas, to the Moscow Patriarchate, which installed its own priests and rallied the faithful behind projects to warm France’s frosty relations with Russia.

When Russian church staff and their lay French supporters broke into the Nice Orthodox cemetery in February and declared it Russian property, allies of Mr. Obolensky hoisted a banner on the iron gate: “Hands off, Mr. Putin. We are not in Crimea or Ukraine. Let our dead rest in peace.”

Moscow’s quest to gain control of churches and graves dating from czarist times and squeeze out believers who look to the Constantinople patriarch is part of a broader push by the Kremlin to assert itself as both the legitimate heir to and master of “Holy Russia,” and as a champion of traditional values against the decadent heresies, notably liberal democracy, promoted by the United States and what they frequently call “Gayropa.”

“The church has become an instrument of the Russian state. It is used to extend and legitimize the interests of the Kremlin,” said Sergei Chapnin, who is the former editor of the official journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, the seat of the Russian Orthodox Church and affiliated churches outside Russia.

Unlike the Catholic Church, which has a single, undisputed leader, the pope in Rome, the Orthodox or Eastern branch of Christianity is divided into more than a dozen self-governing provinces, each with its own patriarch. The biggest of these, the Russian Orthodox Church, covers not only Russia, but also fragile new states like Moldova that formerly belonged to the Russian and later Soviet empires.

“We have been independent for 25 years but our church is still dependent on Moscow,” complained Iurie Leanca, a former prime minister of Moldova, who in 2014 signed a trade and political pact with the European Union that the church and the Kremlin worked hard to derail.

In the vanguard of the anti-European cause in Moldova has been Marchel Mihaescu, the deeply conservative Orthodox bishop of Balti, who was appointed to his post by the Moscow patriarch.

He has warned worshipers that new biometric passports, required by the European Union in return for visa-free access to Europe, were “satanic” because they contained a 13-digit number. He also tried to torpedo legislation extending protection against discrimination in the workplace to gay people, warning that this would draw God’s wrath and sunder relations with “Mother Russia.”

“The voice of the church and the voice of Russian politicians — not all, but the overwhelming majority of Russian politicians — are the same. For me, Russia is the guardian of Christian values,” the bishop said in an interview in a high-ceiling office decorated with a half-dozen portraits of past and current Russian patriarchs and a single picture of Moldova’s own senior priest, Metropolitan Vladimir of Chisinau.

Europe, said the bishop, has “definitely given us lots of money, but wants too much in return. It demands that we pay with our souls, that we alienate ourselves from God. This is not acceptable.”

In their determination to fend off the West, conservative Orthodox priests in Moldova have made common cause with politicians like Igor Dodon, leader of the pro-Moscow Socialist Party.

When gay activists staged a parade this summer in the center of Moldova’s capital, Chisinau, Mr. Dodon rallied his own supporters for a rival event dedicated to traditional values while a group of Orthodox priests gathered nearby to chant prayers and curse homosexuals.

The gay parade, which was joined by a number of Western diplomats, got called off after just a few blocks when it ran into a crowd of protesters waving religious banners and throwing eggs.

Opposition to gay rights has also been taken up with gusto by Russia and the Orthodox Church in Western Europe.

The Institute for Democracy and Cooperation, a research group in Paris headed by a former Soviet diplomat, threw its support behind opponents of a new French law in 2013 allowing same-sex marriage. It organized a conference on “defense of the family,” and promotes Russia and its Orthodox faith as protectors of Christian values across Europe.

Natalia Narochnitskaya, the institute’s head, told an Orthodox Church website run by Bishop Tikhon Shevkunov, a Moscow monk close to Mr. Putin, that Europeans are fed up with what she called the “victory parade of sin” and increasingly look to Russia for guidance and solace. “We have started to get letters at the institute: ‘Thank you Russia and its leader,’” Ms. Narochnitskaya said.

What role the new cathedral complex in Paris might play in this agenda will not be clear until it opens later this year, but those who have studied Mr. Putin’s methods predict it will serve as a megaphone for his take on the world.

“This cathedral is an outpost of the other Europe — ultraconservative and anti-modern — in the heart of the country of libertinism and secularism,” said Michel Eltchaninoff, a French writer and author of “Dans la tête de Vladimir Poutine,” a book about the Russian president’s thinking.

A huge complex of four separate buildings, the “spiritual center” will include not only a church but a school, conference halls and a cultural center run by the Russian Embassy.

The complex is owned not by the church but by the Russian state, which beat out Saudi Arabia, Canada and other countries that had also sought to buy the coveted plot.

Moscow has been looking for an imposing church in Paris ever since the city’s principal Orthodox site, the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, broke with the Russian church hierarchy after 1917 and transferred its allegiance to Constantinople.

Though fervently opposed to religion, the Soviet leaders Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev both pressed Charles de Gaulle to hand over control of the Nevsky Cathedral to Moscow.

He refused, leaving Orthodox churchgoers loyal to the Moscow Patriarchate to set up their own far more modest place of worship in a Paris garage.

Under Mr. Putin the quest to recover church property has resumed with vigor — in tandem with a drive to reach out to far right political forces in Europe seduced by the idea of Russia as a bastion of conservative social and cultural values.

A Corner of the World

The merging of political, diplomatic and religious interests has been on vivid display in Nice, where the Orthodox cathedral, St. Nicholas, came under the control of the Moscow Partriarchate in 2013.

To mark the completion of Moscow-funded renovation work in January, Russia’s ambassador in Paris, Aleksandr Orlov, joined the mayor of Nice, Christian Estrosi, for a ceremony at the cathedral and hailed the refurbishment as “a message for the whole world: Russia is sacred and eternal!”

Then, in a festival of French-Russian amity at odds with France’s official policy since the 2014 annexation of Crimea, the ambassador, Orthodox priests, officials from Moscow and French dignitaries gathered in June for a gala dinner in a luxury Nice hotel to celebrate the cathedral’s return to the fold of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Speaking at the dinner, Vladimir Yakunin, a longtime ally of Mr. Putin who is subject to United States, but not European, sanctions imposed after Russia seized Crimea, declared the cathedral a “corner of the Russian world,” a concept that Moscow used to justify its military intervention on behalf of Russian-speaking rebels in eastern Ukraine. Church property from the czarist era, Mr. Yakunin added, belongs to Russia “simply because this is our history.”

The outreach seems to be working. Unlike the national government in Paris, local leaders in Nice, who mostly represent right-wing forces, support Mr. Putin, even applauding the annexation of Crimea.

After the July 14 terrorist attack on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice by a man driving a truck into a crowd, which killed 84 people — among them were four Russians, including an officer at the St. Nicholas Cathedral — Eric Ciotti, the president of the Nice region, demanded that France seek closer relations with Moscow so as to defeat the so-called Islamic State.

Andrei Eliseev, the Nice cathedral’s Moscow-educated and multilingual senior priest, denied accusations by his foes in the émigré community that he works for Russia’s security agency and blamed hostility against him and Moscow on the feuds of old aristocratic families.

But he said he nonetheless has a duty to serve the state, explaining that the Russian church has effectively been a government department since Peter the Great took control of religion in the early 18th century.

So limited is his room for maneuver, he said, “I need written permission from the state just to move an icon” in the cathedral, which belongs to the Russian government, not the church.

With its control of the Nice cathedral secure and work on the new Paris cathedral moving toward completion, Moscow in February turned its sights on a small patch of Orthodox territory still beyond its control — a cemetery containing the graves of long-dead anti-Communist generals, a former czarist foreign minister, a relative of Russia’s last czar, Nicholas II, and scores of other Orthodox Christians, mostly Russians, who died on the French Riviera.

Christian Frizet, a zealously pro-Moscow French engineer, recalled how he went to the cemetery on instructions from the Russian Embassy in Paris and quickly loosened the lock on the iron gate. “It took me only five minutes and I did not even need a screwdriver,” he said.

Helped by Father Eliseev’s assistant at the cathedral, a former Russian military officer, Igor Sheleshko – who later died in the Nice terror attack — Mr. Frizet then put up a sign declaring the graveyard property of the Russian Federation and secured the gate with a padlocked chain.

Mr. Obolensky and his supporters have since taken down the sign, removed Mr. Frizet’s padlock and replaced it with their own. In a rare truce, it was agreed that each side should have a key.

“They will not stop until they control everything,” Mr. Obolensky said jokingly. “One day the Promenade des Anglais will be called the Promenade des Russes.”