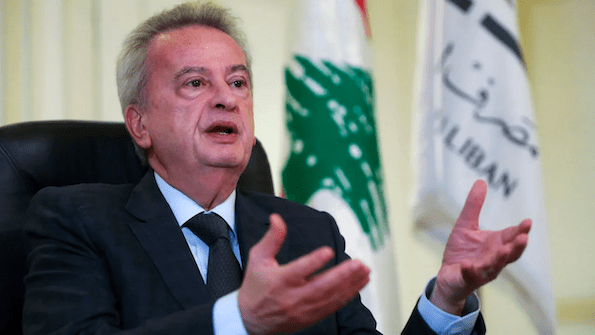

He presided over economic collapse in Lebanon

In most countries, a 95% drop in the currency would be a firing offence for a central-bank governor. Not in Lebanon, which by late 2021 was two years into a grinding financial crisis. The lira, long pegged at 1,500 to the dollar, had plummeted to 27,500. Najib Mikati, the prime minister, was asked if it was time to replace the longtime head of the Banque du Liban (bdl). His answer was clear: “one does not change one’s officers during a war”.

The war is still raging—but even Lebanon’s politicians, it seems, have their limits. The lira now trades at 90,000 to the dollar. gdp has contracted by 40% since 2018. After three decades running the bdl, Riad Salameh at last lost his job on July 31st. No permanent replacement has been announced. But Mr Mikati nonetheless declined to extend his term.

Supporters once called Mr Salameh “the magician” because he kept a stable currency in an unstable country. Like all magic tricks, Mr Salameh’s illusion demanded that the audience not look too closely: his tale is one not just of personal failure and disgrace, but also of a country where politicians refuse to take responsibility for policy.

Mr Salameh was appointed in 1993 by Rafik Hariri, Lebanon’s first post-civil war prime minister. Together they built an economy that relied on massive foreign inflows to finance yawning deficits (the current-account shortfall hit 26% of gdp in 2014) and sustain the currency peg. At its peak, the country’s banking sector held deposits worth four times the country’s gdp.

The scheme began to sputter in 2015, as regional instability and the oil-price crash hurt inflows. To lure fresh deposits Mr Salameh started a scheme known as “financial engineering”. The bdl paid above-market interest rates to borrow dollars from commercial banks, which in turn offered generous rates to depositors.

For a time, everyone was happy: the central bank padded its gross reserves, while banks and their customers enjoyed healthy profits. Nobody in power asked questions. One of Mr Salameh’s former lieutenants says the governor never brought “financial engineering” before the bdl’s central committee for a debate. Nor did parliament perform any oversight.

In 2018 a few bankers and economists tried to sound an alarm. Mr Salameh declared the lira alf khair, “a thousand goodnesses”, a Lebanese superlative. Most of the country took him at his word.

A year later, however, commercial-bank deposits began to shrink. There was no longer enough new money to pay off old obligations. By December 2019 even Mr Salameh could no longer pretend. The lira had slipped from its peg to 2,000 to the dollar. Asked by a television reporter where it would stop, he shrugged: “No one knows.”

Yet no one dared remove him. Mr Salameh had forged close ties with Lebanon’s political, business and media elites, and with powerful foreign patrons like America and France. He had free rein to issue a madcap series of decrees that financed subsidies, imposed capital controls and sought to manage the exchange rate. They hurt depositors, and the country’s foreign reserves have dropped from $31bn in 2018 to $10bn even as the currency collapsed.

The most glaring policy error is Sayrafa, an electronic foreign-exchange platform meant to tame a growing black market and halt wild swings in the lira. In practice it served as a giveaway to banks, importers and other wealthy elites. The Sayrafa rate consistently lags behind the black-market rate by about 20%. Anyone with access to the platform could buy dollars at a discount and resell them on the parallel market. The World Bank estimated in May that such round-trip arbitrage has generated $2.5bn in profits (at the bdl’s expense).

Not that anyone else pursued better ideas. Hassan Diab, the previous prime minister, drafted a decent rescue plan but was blocked by bankers and mps. After three years of bail-out talks with the imf, parliament has yet to pass a restructuring plan for Lebanon’s zombie banks. Even the bad ideas, like holding a fire-sale of state assets to recapitalise the banks, have not advanced beyond talk.

The bdl has four deputy governors, who under Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing rules are drawn from four different sects. In early July they threatened to resign if Mr Salameh’s term ended without a replacement. They have since backed down and offered a few sound policy proposals, among them scrapping the Sayrafa scheme.

Much of what they propose, however, requires assent from politicians who cannot agree on anything. Lebanon has not had a president since October, despite 12 attempts to pick one in parliament. Abbas Ibrahim, the powerful intelligence chief, finished his term in March; he too has not been replaced. Another vacancy looms in January, when Joseph Aoun, the army chief, is due to retire. The country is collapsing, and no one is in charge.

As for Mr Salameh, his retirement is unlikely to be quiet. Authorities in Belgium, France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg and Switzerland are all investigating him for corruption. He is accused of stealing up to $330m from the central bank. Investigators allege that some of the money wound up in his brother’s Swiss bank accounts and that other sums were used to buy property across Europe. (Mr Salameh denies the charges, saying he left a previous job at Merrill Lynch in 1993 with $23m and invested it wisely.)

In May a French judge issued an international arrest warrant after he failed to show up for a hearing. Germany has also filed a red notice with Interpol. Lebanese law does not require him to be extradited, and many observers think the country’s judiciary is too politicised to prosecute him at home. Still, as one former associate bluntly puts it, “he is hated”. For his final trick, the magician may hope to pull off a disappearing act.

The Economist