|

إستماع

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Iran has suddenly been thrust into an election season nobody wanted after its president, Ebrahim Raisi, died in a helicopter crash last Sunday. The leadership vacuum is particularly important because Raisi was widely seen as the likeliest successor to the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is 85 and reportedly in poor health.

The accident comes at a tricky moment amid Iran’s ongoing shadow war with Israel, its proximity to a nuclear bomb, and its struggling economy. How will Tehran manage this enforced leadership transition, and what will it mean for the world? I spoke with longtime Iran watchers Karim Sadjadpour, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and Robin Wright, a contributing writer for the New Yorker and distinguished fellow at the Wilson Center. Subscribers can watch the full interview in the video box atop this page. What follows is a lightly edited and condensed transcript.

Ravi Agrawal: Robin, I’m going to start with you. You’ve described this as a tipping point for Iran. Tell us why.

Robin Wright: It’s a tipping point because Iran is facing so many challenges. Its economy is in perpetual crisis: The value of the rial has gone down 30 percent. Militarily, it has engaged directly with Israel after decades of a shadow war. Politically, Raisi was expected to be the one to oversee the transition after the inevitable death of the supreme leader, who’s been in power since 1989. There has only been one such transition before, from the revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to the current supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei.

Khamenei was president before he became supreme leader. So this threw the whole future of Iran into the air—Raisi was considered one of the two most obvious candidates to replace the supreme leader. Now there is only one: the son of the current supreme leader. If that should happen, it would create, in effect, a theocratic dynasty, whereas the revolution was all about ending having one family control all the levers of power in Iran.

RA: Karim, this is obviously a huge shock for Iran. I’m imagining there will be conspiracy theories about what actually happened. How are Iranians reacting to the news?

Karim Sadjadpour: I was not surprised, but it was remarkable to see the outpouring of joy and celebration among many Iranians who viewed Raisi as this dark, repressive figure. There were fireworks going on in big cities, including his hometown of Mashhad.

But Iran is a polarized society, so there was also a segment of the population that was deeply mourning him. Like any society that has slipped under dictatorship for many decades, the Iranian society has become quite conspiratorial. I suspect the official version—which was that it was an accident—I’m not sure how many people fully believe. There are many potential culprits, perhaps in their views, ranging from Israel and the United States to it being an inside job of individuals who wanted to elbow out Raisi from potentially succeeding the leader.

I think what’s most significant about this death isn’t that Iran needs to find a new president. What’s most significant is that one of the only two individuals who was seen as a serious contender to be the next most powerful man in Iran is now out of the picture.

RA: Robin, you’ve interviewed the last six Iranian presidents, including Raisi, of course. Tell us a little bit more about him. What kind of a president was he? What legacy does he leave behind?

RW: Raisi was arguably the most belligerent of Iran’s presidents—and also the most unpopular. He was one of those absolutist ideologues who believed that Iran has to follow the rigid revolutionary principles and strict Islamic traditions. The big debate in Iran has always been, since 1979, whether the Islamic Republic is first and foremost an Islamic state that follows God’s law—or is it a republic that follows man’s law as embodied in a Napoleonic constitution? There’s been a tug of war all along.

Former presidents like Hassan Rouhani and Mohammad Khatami were centrists or reformists who believe that Iran should move in the direction of a republic where the elected officials have the last word. Raisi has taken Iran in the opposite direction, believing that this is an Islamic state. He will be remembered for overseeing cutbacks that were very unpopular, in the form of subsidies for food and fuel. The economy really took a nosedive during his three years in power. Most of all, he will be remembered for the huge crackdown in 1988, when he was one of four members on a death commission that dispatched something like 5,000 dissidents to the hangman. He was a ruthless justice minister, and he continued that pattern as president.

RA: Karim, this particular supreme leader hasn’t always gotten along with his presidents. Rouhani was seen as too close to the West. So was Akbar Rafsanjani. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was too populist for his liking. Khatami was seen as subversive. But from everything we know, Raisi was the supreme leader’s man. He was loyal. And Khamenei will feel his loss. How will he manage the presidential transition in the coming weeks?

KS: I always thought of Raisi as Khamenei’s mini-me and as someone whom he cultivated for a couple of decades. This is a big blow to him. But Khamenei has a few different options. One of them is for him to introduce his son to Iranians by having him run in the presidential election, just as he did with Raisi. I think that’s unlikely but in the realm of possibility.

Another is you go with someone who has a background in the security forces and the Revolutionary Guards, and perhaps an obvious candidate for that would be Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, who’s the current speaker of parliament and a former Revolutionary Guard commander.

Another option is you find another mini-me. But it’s increasingly slim pickings for finding the Venn diagram of someone who both is a hard-line ideologue and has some managerial competence.

My view is that Raisi’s death really accelerates one of two likely outcomes: Iran’s transition to more of a military dictatorship or, frankly, the regime’s implosion.

RA: Wow. Robin, I’d like you to riff on that as well. I’m also lingering on this idea of a mini-me. The supreme leader is 85 years old, while Raisi was just 63. Raisi was a new generation. And I’m curious how his generation of leaders see Iran’s place in the world.

RW: This is a big divide inside Iran. The majority of Iranians want very much to end their pariah status and want to be part of the international community, whereas the leadership has toughed it out despite the economic challenges posed by the sanctions from Washington.

I think the toughest job in Iran is actually to be a former official. Recruiting somebody will be tricky because they’ll be worried about their own future as well. But the big picture is absolutely the future of the revolution. There have been earlier attempts to reform it in ways that it could gradually reintegrate in the world, and in many ways that was what the nuclear deal brokered by the world’s six major powers was all about in 2015. Once that became ineffective after U.S. President Donald Trump walked away from it, Iran had an incentive again to push on its nuclear program.

I think Iran will probably become the 10th nuclear power. After its disastrous attack on Israel and Israel’s very effective attack on its military leaders in Syria, I think it feels increasingly insecure, even though it has the largest missile arsenal in the world. But there are a couple of obvious candidates, including a former Revolutionary Guard commander named Mohsen Rezaei, who has run several times. It may be that they’re looking for a placeholder since elections are supposed to be held for the presidency a year from now. So it may be that this buys them some time to have someone who’s basically a lame duck, beholden to the supreme leader, but who will not lead the important transition down the road.

RA: Karim, amid all of this, talk to us about what the Iranian people want. It seems to me that voter participation has declined in recent years, right?

KS: I don’t think there’s going to be much popular interest in elections. Very few Iranians still believe that they’re living under a regime that can be reformed via the ballot box. In some ways, I’ve thought about Henry Kissinger’s famous observation that Iran has to decide whether it’s a nation or a cause.

In my view, that was a decision they had to make about 15 years ago, when they reached a crossroad. Whenever they had to make that choice of either reform or repression, they always chose the path of repression. As long as Khamenei is alive, they’re going to stick to revolutionary ideology: death to America, death to Israel, mandatory hijab. For the people of Iran, that’s not a system that’s capable of reform. I think many people won’t vote because voting is perceived as an act of legitimation that they don’t want to do.

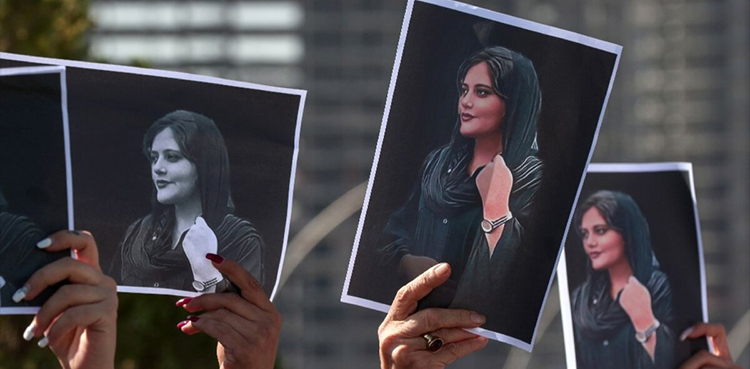

RA: Robin, and just to riff a little bit more on the democracy question, you’ve covered so many protests in Iran, from the Green Revolution movement to the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. I’m curious how that works in terms of repression. Is it just that the regime allows outbursts from time to time to further a facade of democracy?

RW: All of the demonstrations have been surprises and spontaneous. Iranians are a very engaged and sophisticated polity. There have been both economic and political protests across the country, and they have particularly picked up pace since 2017. But the regime cracks down—as we saw in 2022, with the murder of something like 500 people. So I think these tactics and tools will keep being used. The question is what the turnout is going to be at the June 28 election. There is going to be absolute political chaos behind the scenes between now and June 28 over who is going to run. They have to have the candidates vetted by the Council of Guardians. They then have to campaign. In the past, they’ve been having debates among the top candidates. So this is kind of an incredible schedule, and that’s why the regime is probably very engaged in trying to manipulate the outcome so that it is in the favor of someone as close to being a mini-me of Khamenei you can find.

RA: Karim, there’s a clear delta between the aspirations of the people and the aspirations of the regime. How long can that disconnect continue?

KS: It can continue indefinitely. It’s oftentimes more sustainable than people think. There was a wonderful article that was written over a decade ago in the Journal of Democracy called “The Durability of Revolutionary Regimes,” and the basic argument is that authoritarian governments that were spawned from a revolution tend to be more sustainable than just a run-of-the-mill dictatorship, in part because there’s this powerful organizing principle that helps to maintain cohesiveness of the security forces. That has been the case in Iran.

For over 45 years, it’s been a government that has terribly mismanaged the economy and been not only politically repressive but also socially repressive. They try to police every aspect of your life—what you watch, what you drink, if you go out with your boyfriend or girlfriend. But there’s been very few defections from the security forces. So we now have a dynamic in Iran in which you have a regime that perhaps has 15-20 percent popular support but they are united, they’re armed, they’re organized, and they’re ready to kill to stay in power. Repression can’t last indefinitely, but it can often last longer than we think.

RA: Robin, how does the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) fit into this? Will they be looking to strengthen their position?

RW: What’s really interesting about Khamenei is that he had no independent power base when he became the supreme leader. So he turned to the military. And that has been kind of a symbiotic relationship ever since. Many of the Revolutionary Guard commanders end up as his senior advisors. And I think the IRGC, because it has penetrated society, the economy, politics, and every aspect of life, it will have an important role.