If the growing threat of radical Islam and the rise of the far right in the continent were not enough, not to mention the ongoing assimilation and Jewish identity challenges, Europe’s rabbis are forced to deal with internal conflicts and uncooperative community leaders as well.

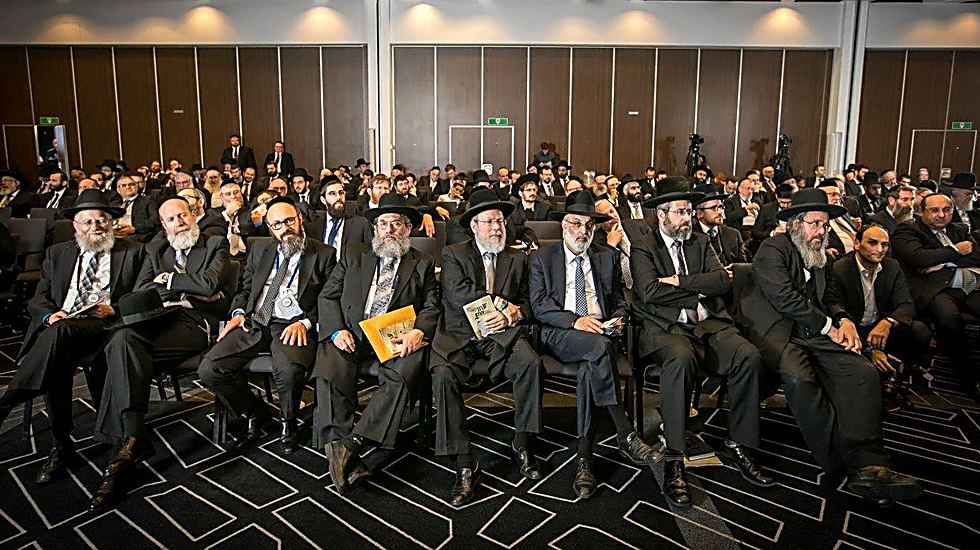

AMSTERDAM—Europe’s rabbis are losing sleep at night: Radical Islam is taking root in the continent, the far right is growing stronger as a reaction—and the Jews, as always, are caught in the middle. Not to mention the assimilation issue and the difficulty of bringing Jews closer to Judaism.Some 300 rabbis and rabbinical judges gathered recently in Amsterdam for the 60th anniversary convention of the Conference of European Rabbis (CER). In dozens of sessions and discussions, they dealt with key decisions on cardinal Jewish issues like conversion courts, kashrut matters, the rabbi’s role, etc.

Senior European Union officials and members of its agency for combating anti-Semitism chose to participate in the convention, as the burning issues on the Jewish community’s agenda are only a microcosm of the issues concerning Europe as a whole: Anti-Semitism, radical Islam, freedom and the far right.

“When I say good morning to the neighbor next door, and meet non-Jewish people as part of my job, I can’t stop thinking about their grandfather murdering my grandfather,” the chief rabbi of Vilnius, Rabbi Shimshon Isaacson, tells Ynet. “This is something which hasn’t gone away and won’t go away, definitely not over two generations.”

He remembers how during one of his tours of the city, he ran into a local man who started accusing him of murdering Jesus. The rabbi didn’t panic and noted pleasantly that if there was any truth to the accusation, he must have supernatural powers that he used to kill a god, which raises the question how dare that man scream at him. “Anti-Semitism is in the European DNA, not in its cognitive part.”

Dealing with ‘Jewish life itself’

Katharina von Schnurbein, the European Commission coordinator on combating anti-Semitism, clarified that “the European Commission can’t accept the fact that 72 years after the Holocaust, Jews still question whether they have a future in Europe.”

CER President Pinchas Goldschmidt, Moscow’s chief rabbi, believes that “it’s in Europe’s soul.” Radical Islam, he says, “wants to return to the Middle Ages, to the era of the caliphs. The far right wants to divide Europe and go back to 1914. We, the Jews, want to march forward and turn to the future with the experience of the past.”

Post-war Amsterdam had 50,000 Jews and as many as 50 rabbis. “Today, there are only 2,000 left,” a local Jew tells me at the Ibis Hotel where we stayed, which caters to Jewish guests.

“Before I became the rabbi of the (southern French) city of Montpellier, I knew there was a ‘Shabbat Jew’ and a ‘Yom Kippur Jew,’” says local rabbi Benhamo. “Now I have learned that there is a Jew of purification, of death.”He says he often holds ritual purification and burial ceremonies for Jews who have already become ‘gentiles for all intents and purposes’ from a genealogical aspect, but what is left from Judaism is the handling of the dead.”Rabbi Isaacson of Vilnius adds with a bitter smile, “Many Jews see themselves as Jews because they belong to the global Maccabi movement, that’s all. Sound strange? Foolish? But that’s how it works.”

Jewish community leaders vs. rabbis

The assimilation rate, which in many cases reaches 90 percent, is also an implication of the unstable Jewish infrastructure. “It’s important for everyone to be Jewish,” a British congregation rabbi explains. “The thing is that if there’s no kosher meat, if there’s no Jewish education or a kindergarten to teach basic concepts, there’s a detachment from the values and from the Jewish communal activity, and it is only then that the barrier of being married to a non-Jewish spouse is lifted.”

The young rabbis are highly motivated, and with the help of the CER and senior rabbinical figures in Europe, they are trying to revive their communities with Jewish education and Zionism. No one here talks about “repentance” in its classical sense, but about instilling basic Jewish values.

The activity is carried out mainly by students, whose age is similar to the rabbis’ age. “Today, everyone understands that the young 15- to 40-year-olds are our future,” says Rabbi Isaacson. “They are the ones who will give birth to children in the community, and they are the ones who will revive and activate it. You can’t work with the old generation when you want to build a community, and when the rabbi is their age and speaks their language, it’s obviously an advantage.”

Surprisingly, however, the rabbis seem to have quite a few opponents in the community itself. One of the rabbis, who asked to remain anonymous, says that “the community committee, which is made up of people who have lived here for years, is afraid of us. It sees our success and it’s afraid that people will get swept away and it will negatively affect their position.”

“This is a familiar phenomenon in many communities,” the young rabbi of Vilnius explains. “The committee or the community leaders maintain a certain Jewish status quo, and every change terrifies them. Many times, they are unwilling, for example, to fund communal activity—beyond putting the synagogue at the rabbis’ disposal. If dozens of people suddenly show up for a lesson or a party around a Jewish issue or event, they ask themselves: When will this harm me? When will the community members ask for other things and dismiss me?”

Aliyah? A sensitive issue

The aliyah issue is constantly present in the air too, although it’s not always explicitly discussed. The Brexit, Marine Le Pen’s impressive achievement and the massive waves of immigration to Europe make it impossible to avoid the issue.

“France is experiencing a serious identity crisis, and there’s no doubt that if Le Pen had won, many of us would have considered leaving and immigrating to Israel, says Rabbi Moshe Sabag of the Great Synagogue in Paris.

The aliyah issue is extremely complicated as far as Europe’s rabbis are concerned. As a congregation rabbi in Germany put it, half joking: “The unofficial response is that if the community members make aliyah, the rabbi would lose his livelihood, as a community with no Jews needs no rabbi, and then what would the rabbi eat?”

They say there is a grain of truth in every joke, but there is a more “formal” answer, the rabbi says: “There are Jews in the community who can be brought closer to Judaism, even if they are currently far. If they go to Israel, they’re more unlikely to move closer to Judaism.”

His comment reflects the perception of many of Israel’s senior rabbis, who have spoken against bringing Europe’s Jews to Israel, fearing a spiritual decline. “People are free to choose,” says Rabbi Weil of France. “I really think this is a matter we shouldn’t intervene in. Each person should know if their time has come to make aliyah.”

It seems, however, that the general heart’s desire is to immigrate to Israel, but there is still a long way to go. As Rabbi Isaacson says, “In my parents’ apartment, on top of my toy chest, there are boxes which they have kept since I was a child. When I asked my mother what’s in there, she said: ‘Those are new instruments which we’ll use when we get to Israel.’ Decades have passed since then. So there’s a great desire at heart, but it’s not an easy road to take, and it could take an entire lifetime.”