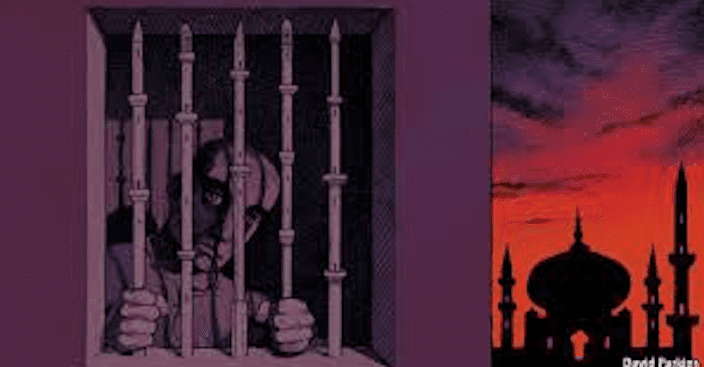

In a country where atheism is a capital offense, nonbelievers are still finding quiet ways to forge community.

For Pakistani atheists, a hitherto intangible demographic, the 2010s was a decade that simultaneously gave them an identity and took it away. The voice they found in the digital sphere at the start of the 2010s, albeit under the cloak of anonymity, has largely been stifled.

With the boom of the internet and the rise of social media, Pakistani atheists and agnostics found safe spaces online around the turn of the decade. This grew into the creation of a Facebook group, Pakistani Atheists and Agnostics (PAA), and an official website in 2011 – the same year that the country saw its most high-profile victim of a blasphemy accusation, former Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer.

The atheist boom online was a grand paradox in itself, given that not only was Islamic terrorism at its apogee at the time, but the Taliban and their apologists enjoyed wide approval and sympathy. And yet mainstream media gave coverage to atheists in the country, with English publications even providing space to some camouflaged critiques of Islam at the time as well.

By 2012, the percentage of atheists in Pakistan had doubled to 2 percent from the 1 percent in 2005, as per Gallup polls – although the sample size of a few thousand might not be accurately representative. The Pakistani census doesn’t categorize atheism, a theological position that carries the death penalty in the country.

Pakistan is one of 13 countries where atheism is punishable by death. Although the Sharia clauses infused in the constitution don’t explicitly mention atheism, under orthodox Islamic interpretations apostasy – leaving Islam – is largely interpreted as blasphemy, which is a capital offence in the country.

This prompted many Pakistani atheists to create an anonymous online identity, which they used to express their religious views on social media, eventually forming groups of like-minded individuals.

“For most Pakistani atheists, PAA and other social media [groups]provided space for their first ever meeting with another Pakistani atheist,” the founder of PAA, who goes by the pseudonym Hazrat Nakhuda, told The Diplomat.

“Pakistani atheists then started having meetups [in the early 2010s]. A lot of very active [PAA members] transformed into actual real life groups of friends,” he added.

The growing space for religious dissent meant that many Pakistani atheists created their own websites and Facebook pages, some of which started garnering large followings. Among these was “Rants of a Pakistani Citizen,” which often used irony and humor to critique both religion and state.

“Initially it was surprising to find out so many people share these opinions. And so many people inboxed me saying there are a lot of posts they agree with, but can’t publicly like or comment on them,” said the founder of the page, known among his followers as Rants, while talking to The Diplomat.

This digital space was swiftly taken away by the state in a five-month span. Pakistan passed its cybercrime lawin August 2016 and then secular bloggers and social media activists were abducted in January 2017.

The draconian cybercrime law ensured that blaspheming online carried the death penalty. Meanwhile, the secular bloggers were abducted under the unsubstantiated pretext of running pages that posted “blasphemous content.” The kidnappings were part of a broader crackdown on anonymity.

“It’s ridiculous that anyone would go after people who are just making memes or posting their opinions. It definitely silenced a lot of voices. If I were in Pakistan, I would definitely be more cautious,” said Rants, whose page has been taken down multiple times by Facebook and banned in Pakistan.

Similarly, the PAA group seized to exist, and its Facebook page was blocked in Pakistan. The last tweet sent out by PAA’s handle was in December 2015.

A member of the then PAA, who goes by the name Billi Musashi, revealed that the group had been compromised.

“There were some people who pretended to be atheists to join the groups and then posted screenshots of conversations here and there – and outed [members]too. [As a result] safe spaces and groups have shut down. There is more distrust [now]– atheists feel threatened,” she told The Diplomat.

The Diplomat has further learnt that the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) and the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) had direct access to PAA. The FIA even summoned admins of other secularist groups over blasphemy allegations.

When the Islamabad High Court (IHC) declared that “blasphemers are terrorists,” PTA chairman Dr. Syed Ismail Shah vowed in court hearings to increase the crackdown. That resulted in arbitrary bans on pages like Bhensa, Mochi, Roshni, and satirical news website Khabaristan Times.

The crackdown by the PTA and Pakistan’s Information Ministry led to the BBC doing a documentary called “Diary of a Pakistani Atheist,” underlining the fear among the atheists in the country while also showcasing how they have carved out a sense of community.

An example of the online crackdown pushing atheists to be warier of the digital space can be seen in how the hashtag #ایک_کروڑ_پاکستانی_ملحد or “Aik crore Pakistani mulhid” (10 million Pakistani atheists) that used to trend on Darwin Day annually, hasn’t done so since 2017.

“Perhaps the person who arranged the aik crore hashtag got scared of the likes of the Tehrik-e-Labbaik. Back in the day our biggest threat was a group of hackers in Zaid Hamid’s group. And we thought that was big!” said Hazrat Nakhuda.

The 10 million figure was a presumed extrapolation from the Gallup survey. However, while recent surveys in other Muslim countries have showed a fast-growing trend of individuals leaving Islam, Pakistan hasn’t had any survey on atheism since 2012.

In fact, atheism in Pakistan has had barely any coverage, not even in the international media, since September 2017 when the United Nations Human Rights Council took up a written statement by the International Humanist and Ethical Union entitled “Dangerous situation for Freethinkers and Humanists in Pakistan.”

In private conversations, many who self-identify as atheists, across the demographic divide, reveal that while there has been a mass exodus of atheist accounts from social media, safe spaces for the freethinkers still exist across the country, including rural areas where many of the PAA members came from.

Many of these spaces exist in educational institutes, ranging from closed groups to open debating societies, which have traditionally allowed room to discuss the philosophical aspects of irreligion as long as one steers clear of mocking Islamic personalities. However, many confess that particular line is getting harder to discern, given how even educational institutes aren’t entirely secure from fatal blasphemy accusations.

The case of Mashal Khan, a journalism student at Abdul Wali Khan University lynched by fellow students in April 2017 is still fresh in memory for many. Junaid Hafeez, a former professor at Bahauddin Zakariya University, has been languishing in prison since March 2013 over a blasphemy allegation that legal experts say wasn’t even worthy of an FIR. The lawyer who took up Hafeez’s case was shot dead in May 2014.

And yet Pakistani atheists say that the trend of abandoning religious orthodoxy has never been higher among the youth as it is today.

“This generation is fast being exposed to other people’s cultures and ideas and is realizing that religious belief is just an accident of birth,” Ali A Rizvi, the Pakistani-Canadian author of The Atheist Muslim: A Journey from Religion to Reason, told The Diplomat.

“A lot of young people write to me and say that’s exactly what I am: an ‘atheist Muslim.’ [Because] many of the Pakistani atheists remain closeted – they are atheists, but have to present themselves as Muslim,” added Rizvi.

Rizvi, who also cohosts “Secular Jihadists,” says his podcast has a large following from Pakistan.

“The ongoing online crackdown isn’t going to affect the growth of atheism in Pakistan. You can temporarily silence them through terror and fear, but you can no longer force people into thinking [certain]things. This is going to severely backfire on the Pakistani state and establishment,” he said.