As the world fixates on Russian spying and cyber-attacks in U.S. politics, the field of sports has been struck by similar intrusions and Canadian athletes and organizations are among the hardest hit.

The Montreal-based World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was warned last summer that Russian hackers were trying to breach its computer system, according to security officials and computer experts who requested anonymity to discuss the matter.

WADA’s former director general, David Howman

The agency’s former director general, David Howman, who reported that he received death threats during his tenure, said these kinds of attacks in sport are unprecedented.

The attacks are believed to be in retaliation for the revelations before the Rio Olympics about widespread Russian state-sponsored doping.

“When you’ve got the stuff that (the Russian whistleblowers) had passed over — although the Russians still deny it — that was mind-blowing, absolutely mind-blowing,” Howman said.

Richard McLaren, a Canadian law professor who has led two investigations into Russian doping, said he changes hotels, rooms and phones often to avoid being tracked.

“I try never to stay in the same hotel because I do not want to create a pattern,” said McLaren, who spoke to the Star in the small tearoom of a boutique hotel in London.

He remains calm, but remains wary and he is not alone.

“Deeply Damaged”

Some experts claim that almost every Canadian athlete who has undergone a drug test during the past 10 years may have had their records hacked.

This proxy war began after McLaren delivered a report to the International Olympic Committee two weeks before the Rio Games.

McLaren substantiated the allegations of Russian whistleblowers that a state-sponsored doping regime affected dozens of sports and thousands of Russian athletes.

The sporting world immediately divided: On one side were the Russians, and, to the surprise of many, the International Olympic Committee and, on the other, were WADA and an array of national anti-doping agencies, including the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), which tests athletes in this country.

The IOC allowed the Russians, with some exceptions, to compete in the Rio Olympics.

In a joint statement, the anti-doping agencies described the system as “deeply damaged” if confirmed cheaters were allowed to participate at the Olympics against clean athletes.

Then the cyber-attacks began.

In September, a group calling itself the Fancy Bears announced it had hacked the international anti-doping computer system that contains the medical records of thousands of athletes.

These records showed the widespread use of Therapeutic Use Exemptions (TUE), which allow athletes to take a banned substance for valid medical reasons.

The group says it is independent and it communicates in a style similar to Anonymous: “We are Anonymous. We are legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget. Expect us.”

Security experts interviewed by the Star say the Fancy Bears is an arm of APT-28, which has connections to Russian military intelligence. The group has been linked to the attacks on the U.S. Democratic National Committee, NATO and European journalists.

Whatever its origins, the Fancy Bears’ hacks galvanized sports.

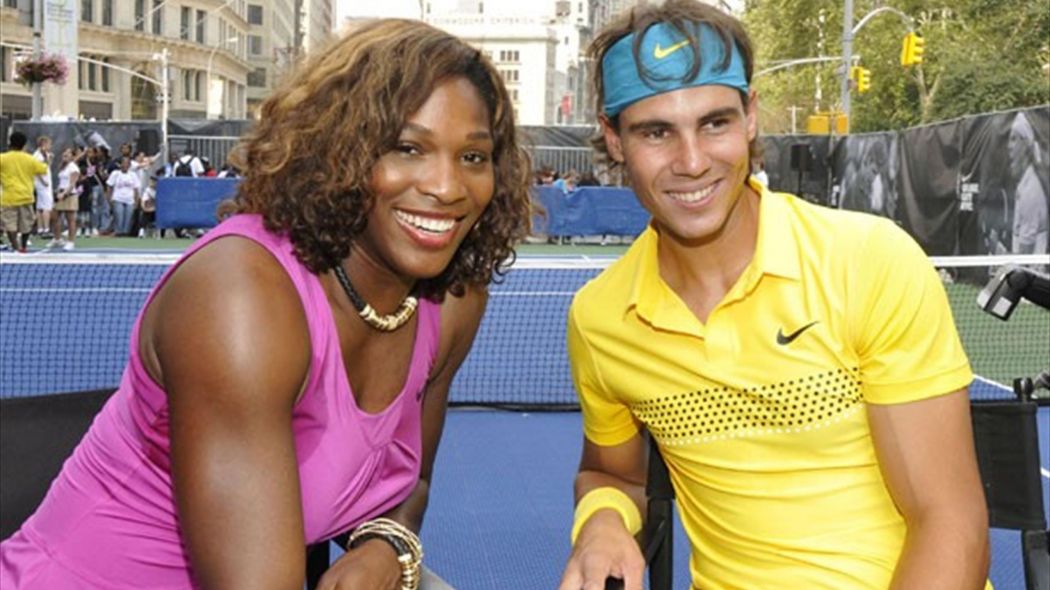

Top international athletes — tennis players Rafael Nadal and Serena Williams, British cycling champions Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome, and four members of Canada’s Olympic medal women’s soccer team, including captain Christine Sinclair — were mentioned in the hacked files.

Although all the athletes have denied any wrongdoing, cyclist Nicole Cooke told British MPS last month that, after seeing the revelations, she was “skeptical” of the British men’s cycling champions and that “taking TUEs just before major events raises questions for me.”

Beckie Scott, the Canadian gold medalist cross-country skier who is the athlete’s representative at WADA, has a different opinion.

Most athletes use TUEs for valid reasons, she said, and the Fancy Bears hack was “an attack on athletes who were actually using the system legitimately and registering their TUEs as they should, so there should be no questioning (of them). There should be no skepticism shone on these athletes for using the system as they had been doing.”

“The World of Craziness”

In November, the hackers announced they had successfully breached the Canadian and U.S. anti-doping agencies. They released TUE records, including information on a dozen Canadians in sports such as rowing, swimming, mountain biking, gymnastics and rugby. The Russian hackers may have accessed thousands of Canadians’ anti-doping records.

Julien Bahain, a Canadian Olympic rower, saw the TUE he obtained after back surgery published by Fancy Bears. “When I was told the news, it was scary,” Bahain said. “This is your medical files. It is intrusive and frightening that this information is out in the public.”

The Fancy Bears also hacked the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sports email system and revealed co-operation between the Canadians and Americans on preparing a lawsuit against the IOC.

“We’re going to continue to stand behind clean athletes and protecting clean athletes’ rights,” said Doug MacQuarrie, a senior executive at the CCES, which shut down its entire computer system to ensure its safety. “It’s really a sad commentary on the ideals of Olympism. . . . They were also exploring things that they could do to make their efforts seem normal in the world of craziness that was going on around the Olympic Games.

“This takes it to a whole new level.”

The Star reached out to comment from Fancy Bears but has not received replies to specific questions.

The ‘Dark Side’

Vitaly Stepanov is a former Russian anti-doping official who, along with his wife, Yuliya Stepanova, a running champion, were the first whistleblowers to expose the extent of Russian doping. They live in hiding to avoid retribution.

Stepanov said he is not surprised by these efforts. “The government of Russia wants to be a super-power by using sport as they do other things. It is very important to them.”

Richard Pound, the Canadian lawyer who helped found WADA, after the doping scandals of the 1990s, agrees that the scale of espionage is unprecedented,

“This is not something that was organized by the CIA or the NATO countries to embarrass Russia. This is a whole bunch of Russians cheating in sport and being assisted to do so by the state agencies, namely the FSB, the new KGB.

“It’s the usual Russian ‘indoor hammer throw,’ when they get caught: denial, threats, lawsuits, conflicting statements. They’re playing a game that is principally for a domestic audience. I don’t think they want the Russian people to know what their government has been doing to achieve all of this success in sport.”

Scott has been deeply shaken by the hacking attacks.

“I came out of that experience a different person than I went into it. That was because I had always acted in my role with WADA as a representative of clean athletes with the higher, greater good and intention.

“Now, I feel like I saw the dark side, and it changed me a little bit.

“I saw the forces we were up against and the lengths that were being gone to to undermine us, and I realized that not everybody is on the same page here.”