Significantly, the security of south Lebanon falls under the total control of Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shia extremist organization that has grown in the last decade to fully control much of Lebanese governmental institutions through its military power, as well as the cooptation and coercion of many of Lebanon’s corrupt political elite.

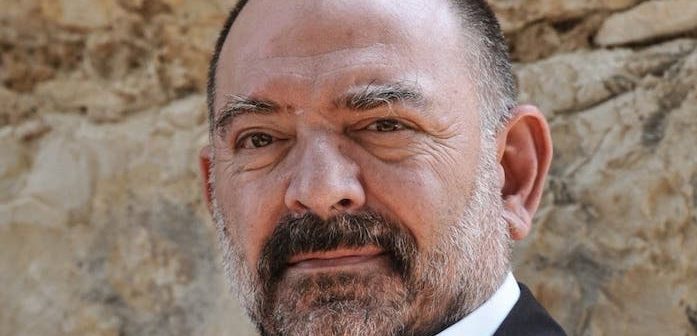

Why was Lokman Slim such a threat to Hezbollah? He was a well-known prolific, articulate, and dynamic activist and director of several cultural institutions, and made frequent appearances on Lebanese and Arab satellite TVs. He fearlessly criticized Hezbollah’s hegemony on the Lebanese state, presenting well-informed and factually based analytical arguments. But most importantly, he was also a Shia intellectual, and thus he represented an opposition to Hezbollah from within its own religious community.

This is quite significant in a country that is deeply divided along sectarian lines and where religious communities tend to support the de facto leader of their religious community out of skepticism towards other communities. This is where Lokman’s distinction resided: As a Shia opponent from within, he could not be easily dismissed as an outsider who conspired against the Shiites, while his strong arguments that attracted international attention could not be easily ignored.

Lokman Slim knew the Shia religious and intellectual heritage too well. He precisely used this knowledge to contest the hegemony of the Islamic Republic of Iran on Shia Islam and on Lebanese Shiites in particular. Through his political analysis and TV commentaries, he staunchly and unyieldingly criticized the hegemony of Hezbollah on the Lebanese state, and its role as a military proxy that implemented the Iranian agenda in both Lebanon and Syria.

Since 2012, Lokman Slim and his Shia fellow activists have been receiving threats against their lives, the most notable of which was the statement by Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah in 2015, in which he said he was not going to tolerate any more the opposition of Shia activists whom he labeled “the Shiites of the US Embassy,” in a bid to frame them as US spies.

Defamatory campaigns have been systematically waged against these activists in recent years by Hezbollah-affiliated newspapers and TV stations, labeling them as traitors, sell-outs, and US spies, and warning them to look out for their lives if they do not desist.

Along with his political activism, Lokman Slim directed several cultural projects through his research center UMAM. His most significant project was the archival documentation of the collective memories of the turbulent past of Lebanon, including the Civil War of 1975-1990. He wanted to preserve the social identity of the region of southern Beirut, that came to be known as Dahiyeh, and lately became the headquarters of Hezbollah.

Many Lebanese came to fear this area as it became associated with negative social realities fostered by Hezbollah: Weapons, militiamen, surveillance of everyday life, Khomeinist ideological propaganda, police-like censorship, and drug trafficking.

But Lokman Slim was a resilient maker of cultural resistance against Hezbollah’s hegemony: Through arts, cultural projects, archival work, films, photographic exhibitions, he celebrated the preexistent cultural diversity that Hezbollah tried so hard to suppress. He resisted by first physically persisting in their geographical milieu, which was his ancestral home anyway, and secondly by persevering with his cultural projects and publications. He contested that geographical space dominated by Hezbollah through safeguarding the memory of a pre-Hezbollah world, in which tolerance and diversity prevailed: When Muslims and Christians lived together in one neighborhood, right-wing activists shared public space with leftist activists, and women flaunted their liberty fearlessly.

That was the world of Dahiyeh before Hezbollah occupied this space and created an Orwellian world that is religiously and militaristically surveilled, controlled, and ideologically censored according to the Iranian model.

In fact, Dahiyeh, under Hezbollah, has been turned into a militarized bastion that flagrantly professes political allegiance to Iran, and remains festooned with iconography praising the Islamic Republic. One can find humongous figurines of Khomeini and Qassem Soleimani, flags of Hezbollah and Iran, banners and posters displaying propaganda slogans, and portraits of thousands of young men who died fighting in the wars of Hezbollah. The public space is periodically occupied by military parades, while public microphones, permanently installed in the streets, broadcast ideological material, including speeches made by Nasrallah along with religious and militaristic chants.

In response, Lokman Slim resisted by creating cultural spaces for debate, dialogue, and politically artistic expressions. For Lokman, research, political analysis, and political art, were all acts of resistance in the face of totalitarianism, the militarization of society, and the oppression of freedoms.

Lokman’s family is adamant on preserving his legacy. His sister Rasha al-Ameer wants to keep the publishing house ongoing, while his wife Monika Borgmann plans to keep operating the research center UMAM. More than any other time, it is pressing for liberal democracies to show support for the liberal activists in Lebanon and the Middle East. If these activists are left on their own to fight for freedom, they will be exterminated one after the other by the new forces of fascism in the Middle East.