Image from May 2016 ISIS video in support of ISIS Sinai Wilayah

The social media phenomenon that is the Islamic State seems to have peaked in early 2015.[1] The sheer size and adaptability of the ISIS media operation is still impressive, but efforts by social media companies, law enforcement, and the results of Coalition air strikes have at least made the efforts of the Islamic State to communicate more difficult. Even if none of these steps had been taken, ISIS does face obstacles common to many in our disposable culture: the need to constantly be providing fresh content and to be successfully competing for attention in a distracted marketplace.

The fact that ISIS “surges” in the production of targeted materials after a notable attack, such as Paris in November 2015 or Brussels in March 2016, is not that surprising.[2] In those circumstances, the “success” generates a cluster of videos, commentary, a dedicated hashtag, and other tools to focus attention and milk the maximum amount of publicity from a terrorist act. This connection with an attack and the media follow-up is the “Propaganda of the Deed” on an industrial scale.

But more interesting is how ISIS has, on six occasions in the period between September 2015 and May 2016, surged to produce an Arabic-language targeted media campaign, characterized by the synchronized release of multiple videos from the different ISIS Wilayat (provinces), focusing on a specific topic not immediately connected to a high profile ISIS operation.

These six targeted media campaigns have been the following:

- Syrian refugees (September 2015)

- Somalia (October 2015)

- Palestine “knife intifada” (October 2015)

- Saudi Arabia (December 2015)

- The “Islamic Maghreb” or North Africa (January 2016)

- Sinai (May 2016)

Organizing around a specific theme is not new, of course. One of the tactics that ISIS took from the Syrian Revolution was the tradition of Hashtag Fridays, and the nascent Caliphate in the summer of 2014 would use weekly hashtags such as #CalamityWillBefalltheUS to coordinate twitter storms. The campaigns under study were more narrowly focused and occurring at a time when the still-considerable media resources available to the Islamic State are slowly declining.

Two of the campaigns – on the flood of Syrian refugees heading to Europe and the effort to piggyback on a series of knife-wielding Palestinian murders of Israelis – are clear attempts to influence or take advantage of news events completely disconnected from the Islamic State but that ISIS believes are important in and of themselves. Despite the organization’s much-vaunted media prowess, neither campaign, on the surface, appears to have been particularly successful.

The Syrian refugees campaign, launched September 16, 2015 and organized under the hashtag “Refugees_to Where?” (#لاجئون_إلى_أين) featured 13 videos released from ISIS provinces in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.[3] The campaign sought to urge refugees not to flee to the infidel West but instead to choose a path of greater dignity by immigrating to the Islamic State. Refugees fleeing to the West are described as being in danger of greater humiliation and abuse in the Land of Unbelief (Dar al-Kufr), including falling into the trap of being Christianized (with stock footage of the Vatican and Pope Francis).

While it is clear now that ISIS did use the Syrian refugee flood to infiltrate some terrorist operatives into Western Europe, there is no evidence that the propaganda in any way dissuaded the mass of desperate Syrian people from trying to find refuge in Western Europe. The fact that Sunni Arab Muslim Syrians, supposedly a core demographic for ISIS, continue to try to flee is a graphic rejection of Islamic State threats and blandishments.[4]

If the ISIS media blitz on Syrian refugees wanted to shape a negative news story in its favor, the material associated with the knife intifada beginning October 19, 2015 sought to associate ISIS with a “positive” (from the point of view of ISIS) local development. ISIS came rather late to the story, as unrest and lone-wolf attacks had spiked in September, with the first stabbing occurring on October 3 near the Lions’ Gate in Jerusalem’s Old City.[5]

The content of the 10 videos in this campaign varied slightly according to Wilaya, but often consisted of images of past conquests – horses, cavalry, and scenes from the 2005 film “Kingdom of Heaven” – and of advances by the Islamic State. ISIS spokesmen would send greetings from the “soldiers of the Caliphate” to the mujahideen and muwahidun (the Muslim people of strict monotheism) in Palestine, calling on them to rise up and deepen their struggle. One video from ISIS Homs asked, “Where are the fighters in the land of Palestine?” Still another video, from ISIS Damascus, featured a masked Israeli Arab calling, in fluent Hebrew, for violence both on the West Bank (called “the Islamic Bank”) and inside Israel.

There was, of course, considerable local incitement and glorification of the attacks by Palestinian political and religious leaders independent of anything said by the Islamic State. And while the stabbing attacks have continued into 2016, there seemed to be no large “bump” or extra impetus occurring after the launch of the Islamic State’s flurry of online material.

The four other campaigns of video clusters seem to be even more aspirational, trying to seize upon a perceived opportunity for expansion. The October 1, 2015 launch of Somalia-related videos by ISIS provinces in Syria, Iraq, Sinai and Yemen were at least connected to actual efforts by a pro-ISIS faction of fighters within Al-Shabaab to gain traction.[6] In addition to the seven videos, the campaign included a coordinated campaign on Twitter, under the Arabic hashtag #O_You_Mujahid_in_Somalia, with pro-ISIS accounts tweeting materials calling for support from Al-Shabab fighters as well attacks on Al-Qaeda and its leader Ayman Al-Zawahiri. An eighth Somalia-focused video, the sole contribution from ISIS West Africa (Boko Haram), was released a little later than the rest.[7]

To this day, the pro-ISIS faction of fighters in Somalia seems to have remained rather small, so small that it is not yet designated an ISIS Wilaya. While one prominent leader, the former UK-based Abdul Qadir Mumin, declared his allegiance to the Islamic State on October 23, Somali security sources estimated that ISIS could call on the loyalty of less than 10% of all Al-Shabab fighters.[8] Success has been limited, and the dominant pro-Al-Qaeda faction of Al-Shabab has hunted down and killed several of the younger pro-ISIS renegades. A potentially high-profile attack on a Kenyan bus by the ISIS faction was thwarted in December 2015.[9] The same seems to be true of a possible recent ISIS Somalia anthrax attack.[10] ISIS Somalia leaders have so far been unable to mount spectacular attacks such as Al-Shabab’s 2013 Westgate Mall slaughter or 2015 Garissa University attack.[11]

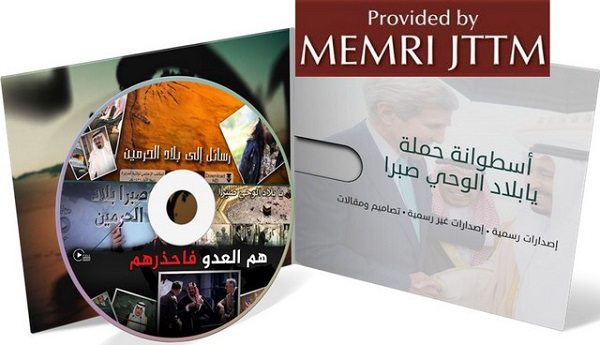

The largest single cluster campaign to date was probably that launched on December 16, 2015, targeting Saudi Arabia.[12] Of course, Saudi Arabia was and remains a key well-known objective of both ISIS and Al-Qaeda, and the campaign coincided with the launche of the Saudi-led “Islamic Coalition” supposed to coordinate the fight of Muslim nations against “terrorist organizations.”[13] Six GB of complementary ISIS Saudi campaign material was posted online as a downloadable CD by the Al-Battar Media Foundation on December 28. It included two videos, eight articles, and 50 posters.

In addition to Al-Battar’s contribution, a total of 15 videos, ranging from five to 30 minutes in duration, from ISIS provinces in Syria, Iraq, Libya, Sinai, and Yemen called on Saudis to open their eyes to the supposed treachery, apostasy, and corruption of the Al-Saud ruling family (whom they insultingly dubbed Al-Salul, “the infiltrators”). The videos also called for following Islamic tradition and expelling all non-Muslims from the Arabian Peninsula, and for waging all out sectarian war against the kingdom’s Shi’a population. One speaker, on the ISIS Anbar video, called for killing infidels currently living among the local population: “They are among you and on your streets, there is no easier way to kill them and there is nothing more delicious than spilling their blood, so kill the polytheists wherever you find them…” Another noted that the Al-Saud are more evil than the Christians and Jews.

Again, the overkill of launching so much material on one subject does not seem to have paid off right away. This oversaturation of the jihadi social media space did not lead to any sort of immediate spike in attacks or pledges of loyalty to the Islamic State. There may be some sort of internal dynamic at play here as well, with the constant competition against AQAP and a sense that Saudi Arabia is increasingly vulnerable under the elderly King Salman. Part of the attraction for ISIS is also that Saudi Arabia is both a place with an affinity for the ISIS discourse and a key player in fighting the Islamic State.[14] ISIS attacks on Saudi Arabia seemed to have remained more or less steady over the past year, with one attack on an average of every 12 days.[15]

The January 19, 2016 media cluster offensive against North African countries was orchestrated under the Arabic hashtag #Al-Maghreb_al_Islami. The 11 videos from Syria, Iraq, and Sinai wilayat lumped the leaders of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya together as puppets of the former colonial powers, of being implementers of “an indirect occupation,” and as tyrants to be opposed and overthrown and, like Somalia, encouraged Al-Qaeda supporters to switch their loyalty to the more successful ISIS Caliphate.[16] Several videos noted that North Africa had been the historic jumping off point for the conquest of Western Europe.

The Islamic State also attacked religious leaders in those countries, with a specific focus on Morocco’s Sufi Muslim establishment. The bitter tone on Sufis, the condemnation of their practices as un-Islamic, and the call for the destruction of their shrines seemed at times to surpass the vitriol directed at rulers. Among the charges made against Morocco’s King Muhammad VI was that he pardoned and expelled a Spanish pedophile in 2013, an act that provoked rioting inside Morocco.[17] The pedophile was now dubbed “a Crusader” by ISIS.

The latest large scale media campaign, launched on May 5, was in support of the ISIS Sinai franchise and sought to tie together the work of that outfit, “the Caliphate,” the regime of Egyptian President ‘Abd Al-Fattah Al-Sisi, and the Jews and Jerusalem. This campaign almost matched the Saudi one in terms of the number of videos released, with a total of 14 from ISIS provinces in Syria, Iraq, and Libya. Indeed, several of the videos worked a Saudi-Israeli angle, capitalizing on the recent visit of King Salman and news of a bridge to be built across the Gulf of Aqaba between the kingdom and Egypt, emphasizing that the Jews will manipulate the Salul to build this bridge but that the mujahideen will use it to conquer Arabia.

A typical video from this campaign, such as the one from the ISIS Al-Jazirah branch (the area around Tal Afar and Sinjar in Iraq), began with news footage (including from Al-Jazeera TV) accusing the Egyptian military of war crimes in Sinai, allegedly by targeting homes, mosques and civilian vehicles. It praised the “lions of Sinai who are fighting the dogs of Al-Sisi,” and, like so many other ISIS videos, featured a local fighter talking to the camera, praising the Islamic State, and encouraging the target audience to take action and support ISIS.

Not surprisingly, another target in the Sinai videos, aside from the Egyptian government and Israel, was the Egyptian opposition, especially the Muslim Brotherhood. In this narrative, the tyrant Mubarak was replaced by the tyrant Morsi, who in turn was replaced by the tyrant Al-Sisi. The ISIS Egypt campaign was large and impressive, but not unprecedented.[18]

A step beyond the work of publicizing their own activities, these six intensive media campaigns featuring clusters of videos are an attempt at propaganda power projection. Despite the apparently limited concrete results, Islamic State media experts must regard them as somewhat useful in saturating the jihadosphere and attempting to create opportunities and undergird new operations in places where they see potential growth, by both poaching from Al-Qaeda and subverting fragile regimes.

These campaigns also underscore the relative pecking order in the Islamic State universe, with most video productions coming from the ISIS heartland in Syria and Iraq. Yemen, Libya, and Sinai make only occasionally contributions. All of the material is in Arabic (except one speaker using Hebrew) intended for that key audience. Non-Arab ISIS branches, such as Boko Haram or Khorasan, make little or no contribution.

The astonishing ISIS conquest of Mosul in June 2014 was essentially supported by one – long and ambitious – video.[19] Like the circumstances of U-boat commanders late in World War II, the media environment for the Islamic State is not as permissive as it used to be in the early days of the conflict.[20] A beheading video in 2016 does not carry the same shock and novelty value that one did two years ago. And while this sort of intensive campaign may seem like overkill, it is akin to a baseball or basketball player making multiple efforts to recreate the effect of an amazing past success by taking lots of shots or swings. Although none of these clustered videos are as long as the May 2014 “Clanging of the Swords, Number 4,” ISIS hopes to be able to expand synergies between the virtual world and the real one in some very specific areas. With the region in such disarray, they hope that if they keep trying they will eventually succeed.

* Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice-President of MEMRI.

Endnotes:

[1] Cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Berger_Occasional%20Paper.pdf.

[2] MEMRI JTTM report ISIS Newspaper Says Brussels Attacks Exposed Fragility of European Security Systems, Encourages Jihadis To Carry Out More, March 29, 2016.

[3] MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis No. 1187, The Islamic State’s Frantic Response To The Wave Of Refugees Fleeing Syria, September 28, 2015.

[4] Csmonitor.com, September 21, 2016.

[5] MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis No. 1195, ISIS Campaign: Encouraging Palestinians To Carry Out Lone Wolf Attacks, October 20, 2015.

[6] MEMRI JTTM report ISIS Steps Up Efforts To Divide Somali Al-Qaeda Affiliate Al-Shabab, Calls On Its Members To Join ISIS’s Ranks, October 2, 2015.

[7] Breitbart.com, October 15, 2015.

[8] CNN.com, October 23, 2015.

[9] BBC.com, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35177394

[10] Dailysignal.com, May 6, 2016.

[11] Independent.co.uk, December 24, 2015.

[12] MEMRI Inquiry & Analysis No. 1217, ISIS Campaign Targets Saudi Arabia, Calls For Attacks Against Saudi Monarchy, Shi’ites, And Polytheists, January 5, 2016.

[13] Aljazeera.com, December 15, 2015.

[14] Foreignpolicy.com, September 10, 2015.

[15] Awsat.com, May 2, 2016.

[16] MEMRI JTTM report ISIS Launches Campaign Urging North African Muslims, Al-Qaeda Members To Join Its Rank, Target Local Governments, January 21, 2016.

[17] Reuters.com, August 5, 2013.

[18] Huffington Post, May 12, 2016.

[19] Jihadica.com, May 19, 2014.

[20] Thecipherbrief,com, March 9, 2016.