The Supreme Leader’s two New Year’s speeches provide a valuable look at the regime’s internal dynamics as it attempts to balance economic concerns, electoral maneuvers, regional pan-Shiite issues, and the nascent policies of a new American administration.

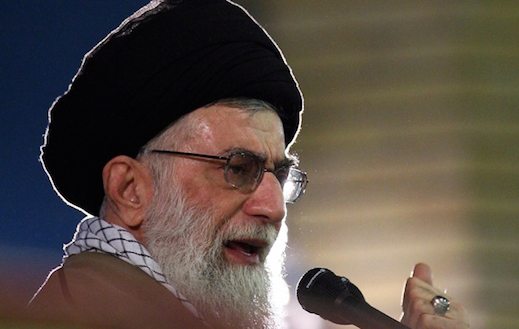

On March 21, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei delivered his annual Nowruz speech in the holy city of Mashhad, his most important public address of the year. In addition to setting the stage for the country’s upcoming presidential election, his remarks focused on domestic economic issues as usual, but without much of the anti-American belligerence that has colored past New Year’s speeches.

FROM THE AIRWAVES TO THE SHRINE

Since becoming Supreme Leader in 1989, Khamenei has delivered two Nowruz speeches every year. The first is a recorded address known as his “Nowruz message,” which is traditionally broadcast on state television and radio immediately after the vernal equinox (March 20 this year). He usually speaks about fifteen minutes while sitting in a chair alone in a room — an understated contrast to his subsequent public speech before massive crowds in a Mashhad shrine.

In his third year as Supreme Leader, Khamenei added a new permanent component to his Nowruz messages: labeling them with short motto-like phrases. While these labels have occasionally honored historical figures, they usually emphasize ideologically loaded economic themes, whether directly or indirectly. This practice is Khamenei’s way of clarifying his economic expectations in the hope of encouraging officials and citizens to better meet them, highlighting his fixation on the country’s increasingly ailing economy.

The motto for this year’s televised Nowruz message was “Resistance Economy: Production and Employment,” invoking his oft-stated policy of circumventing international sanctions by adjusting Iran’s economic practices. The address itself bluntly accused President Hassan Rouhani’s government of failing to bring its economic policies in line with the expectations of the Supreme Leader or the people: “Most of the current bitterness and difficulties are related to people’s economic problems.” Khamenei did not say a word on the P5+1 nuclear deal or Iran’s relations with the West.

In sharp contrast, President Rouhani’s own New Year’s message trumpeted his government’s successful economic record. He called the recent economic growth and the decline in Iran’s unemployment rate “unprecedented” in the past twenty-five years. He did not mention any problems in that regard, instead emphasizing issues such as the “positive role of the resistance economy,” the government’s ongoing implementation of the nuclear deal, Iran’s increasing proportion of non-oil exports over imports in the past two years, and Tehran’s successful “petrol diplomacy,” which in his view has allowed the country to regain its previous stature in global oil and gas production.

WHY MASHHAD?

Khamenei’s second Nowruz address is typically a public speech delivered before a massive crowd at the Imam Reza Shrine in Mashhad. This annual trip plays a ritual role in maintaining his legitimacy as Iran’s Supreme Leader, as “the leader of the Muslim world” (according to state propaganda), and as head of the regional Shiite community. Iranian rulers have long defined themselves in the latter terms as part of their self-described politico-religious role of protecting all Shiites at home and abroad — a task that includes safeguarding the frontiers of any Shiite territory (e.g., that of the affiliated Alawite regime in Syria).

Mashhad is not the main seat of the global Shiite clergy (that title goes to Qom), but it is the holiest Iranian locale for Shiites because it contains the shrine of the all-important eighth Imam, Ali Reza. Against that backdrop, Khamenei’s decision to make Mashhad the site of this major annual address — and thus the symbolic seat for his national and transnational leadership — seems well calculated. For the most part, his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini never ventured much outside Tehran following the 1979 revolution, nor made any official stays at sacred sites. Yet Khamenei lacks the charisma and natural legitimacy inherent in being the Islamic Republic’s founder, so regularly associating himself with Iran’s holiest city is the next best thing.

Indeed, selecting such a place and time for the year’s biggest speech is anything but accidental. Every year, Mashhad receives hundreds of thousands of domestic and foreign pilgrims around Nowruz for religious and recreational reasons. On March 20, Iranian tourism spokesman Mehdi Firouzan stated that more than 1.5 million pilgrims had traveled there for the 2017 holiday. For Khamenei — who is very sensitive about the number and type of people who receive him during official visits anywhere in the country — Nowruz in Mashhad is matchless because it guarantees him a massive crowd (albeit one that is not really there for his sake). It also allows the regime to carefully plan his costly annual trip in an almost theatrical way, making it look purely spontaneous while at the same time reflecting an air of almost regal grandeur absent from other speeches (this differs from his usual program when visiting other cities, where local officials encourage or force screaming crowds to run after his car when he arrives, essentially transforming the welcoming ceremony into a wild public carnival). For both symbolic and logistical reasons, then, he has consistently scheduled the speech for the first day of the New Year (March 20 or 21) since 1997.

WHAT DID HE SAY?

Given the prominence of Khamenei’s Mashhad address, he generally uses it to spell out his most pressing concerns and criticisms. Compared to his 2016 speech, this year’s address was shorter in length and much lighter in content, though a good portion of its importance lies in what was left unsaid.

Last year’s speech began with the economy, including Khamenei’s usual advice for improving people’s living conditions, becoming more self-reliant, and the like. Yet he quickly shifted to the nuclear deal, downplaying the effectiveness of diplomatic negotiations with America while warning listeners not to stray from the regime’s ideological principles and policies. He then provided an extensive account of Washington’s supposed propensity for cheating on agreements and breaking promises, outlining in detail how it purportedly did so on the nuclear deal’s terms. Indeed, the long anti-American portion of speech defiantly bashed the United States with inflammatory rhetoric, repeatedly called it the “enemy,” encouraged listeners to avoid overestimating American power, and counseled them on how to resist and neutralize U.S. economic pressure.

This year, Khamenei likewise began by focusing on economic issues, calling them “the country’s top-priority problem” and providing his familiar suggestions on the matter. Yet this week’s speech diverged sharply from last year’s on two fronts.

First, Khamenei spent a fair amount of time discussing Iran’s imminent presidential election, currently scheduled for mid-May. This included heavy criticism of those citizens who took to the streets in protest of the rigged 2009 election. After his typical exhortation to boost turnout (“Enthusiastic participation of all eligible voters in the election will add to Iran’s pride, authority, and credentials”), he offered a clear warning against any new unrest: “I never intervened in an election, and I do not tell people who they should or should not vote for, but if some individuals decide to stand against…the people’s vote by making trouble, I will intervene and confront them.”

Second, and most important, the Supreme Leader said little about domestic or foreign “enemies of the revolution,” and nothing about America. Similar to his televised March 20 message, the March 21 address was one of the mildest in the history of Khamenei’s Mashhad speeches, marked by a striking lack of threatening, defiant, or harsh rhetoric against such enemies. His decision to refrain from saying even a word about two of his favorite topics, America and the nuclear deal, is quite meaningful. Contrary to concerns that President Trump’s harsher tone toward Iran would spur the regime to become more belligerent, Khamenei’s keynote address of the year was silent about the United States. Similarly, the speech is at least an initial sign that a firmer U.S. stance may not embolden the hardliners too dramatically or undermine the reformists. At the very least, Khamenei did not appear to boost the prospects of those hardliners opposing Rouhani in the election, and the president seems well positioned to win a second term.

Mehdi Khalaji is the Libitzky Family Fellow at The Washington Institute and author of its recent study The Future of Leadership in the Shiite Community.